For many people the notion that a college or university could restrict admission because of one’s race, religion or gender is unthinkable. But that was the case just 70 years ago when Roosevelt University was founded. At that time, the majority of people attending colleges in the United States were white Christian men.

On the occasion of the University’s 70th anniversary, we asked University Historian Lynn Weiner to examine why the founding of Roosevelt was such an extraordinary occurrence in the history of social equality and why it was a success from the very beginning.

In nineteen forty-five, 70 years ago this year, Roosevelt College was created in a courageous effort to make higher education more democratic. It was born into a world where racial, gender and religious segregation dominated colleges and universities, in a nation where fewer than 20 percent of high school graduates went on to higher education and in a city where stores, restaurants, housing and recreation excluded African Americans.

College choices were limited in Chicago during the early 1940s. The only comprehensive public university was 140 miles away in Urbana-Champaign, until the University of Illinois opened a two-year campus for freshmen and sophomores on Navy Pier in 1946. Local options included professional and teacher-training colleges, junior colleges, Catholic schools and the University of Chicago and Northwestern University.

Bigotry further restricted college opportunities. Many private colleges and universities at this time – including Northwestern – imposed admissions quotas on the number of Jewish, Catholic and black students they would accept. To screen out “socially undesirable applicants,” they required photographs, personal interviews or the names of all four grandparents on applications.

The number of black enrollees at selective schools was miniscule and their applications discouraged. Princeton University, for example, would not admit black students until 1945. Public universities also discriminated by race. It was not until 1948 that the University of Arkansas admitted its first African-American student. Northwestern, which did admit up to five black students a year in the 1940s, excluded these students from on-campus housing until 1947.

Jewish students were held to quotas of between 2 and 15 percent as universities responded to what they termed the “Jewish problem.” These discriminatory admission policies, which had begun in the 1920s, persisted until the mid-1960s.

One exception was the Central YMCA College in Chicago. Opened in 1919, by 1941 it enrolled a diverse group of 2,240 men and women and identified itself as “liberal in spirit.”

By the early 1940s, however, the Y’s 16-member Board of Directors comprised mostly of local businessmen and bankers had grown uneasy with the rising numbers of “undesirable” black and Jewish students in the classrooms and hallways. They feared these students would drive away white Protestant applicants. In addition, despite the “liberal spirit” of the school, there were rigid racial restrictions in place. Black students, for instance, were expected to pay athletic fees but were not permitted to use the swimming pool, which was operated by the YMCA.

The president of the college was Edward “Jim” Sparling. A Stanford-educated psychologist, he arrived at the Y College in 1936 and found himself in increasing conflict with the YMCA over three major issues – admissions quotas, discrimination and academic freedom. When the Board told Sparling to prepare a census of the racial and religious composition of the student body, he refused, saying, “We don’t count that way.” In February of 1945 he was told to resign.

President Sparling and his supporters immediately lobbied for a “friendly separation” from the YMCA and planned a new school – initially called Thomas Jefferson College – that would offer admission and equal rights to any qualified student. They sought financial backing from Marshall Field III, the Rosenwald Foundation, labor unions and progressive Chicagoans.

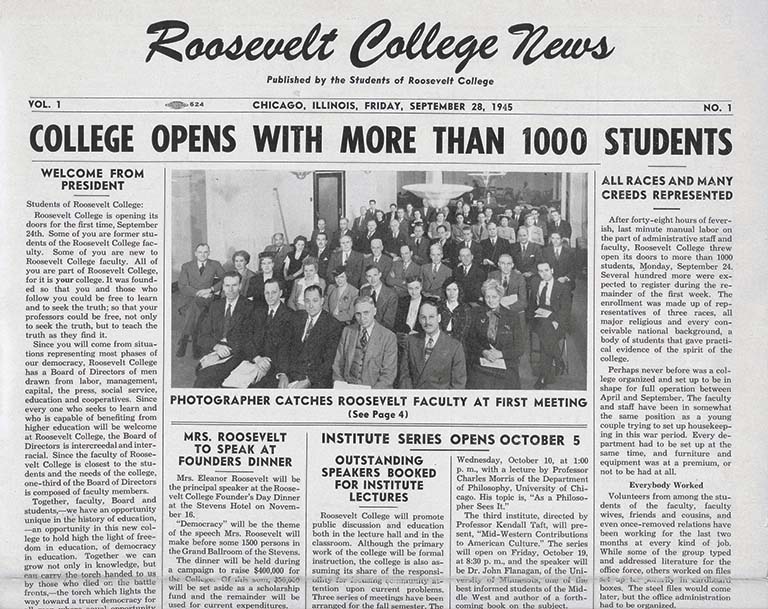

When efforts to interest the Y in this project failed, Sparling formally resigned on April 17, 1945, and in a walkout surely unique in American higher education, 62 faculty members resigned in his support and signed a document condemning the “illiberal and discriminatory purposes” of the Board. A student resolution soon followed, favoring separation from the Central YMCA College by a vote of 448 to 2. President Franklin Roosevelt had died on April 12 and two weeks later the new school was renamed Roosevelt College.

Edwin R. Embree, a friend of FDR, head of the Rosenwald Foundation and first chair of Roosevelt’s Board of Trustees, said the new school “embodies the democratic principles to which President Roosevelt gave his life – the four freedoms in action . . . Roosevelt College of Chicago will practice no discrimination in students or faculty and no restriction of class or party line in its teaching or research.”

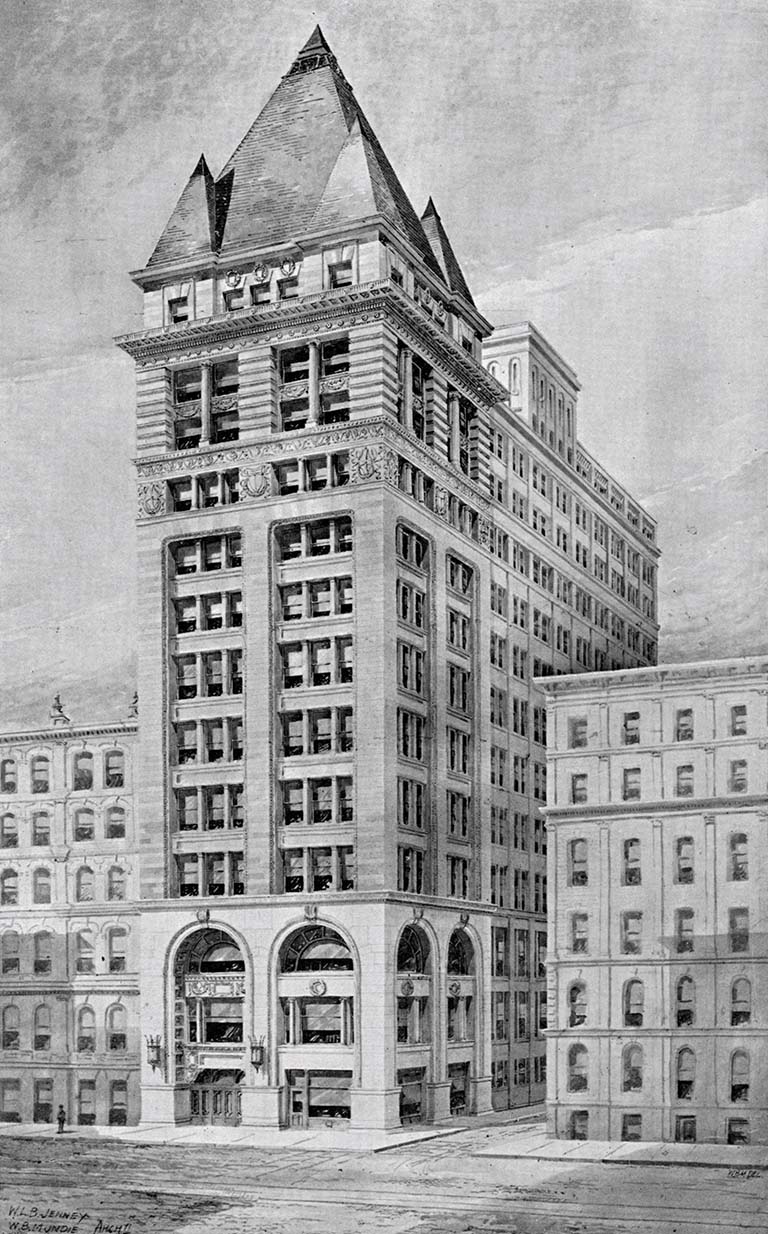

The College now had a mission, a name, a faculty and students, but no money, classrooms, labs or library. The new Board of Trustees, which included African-American chemist Percy Julian, was undoubtedly one of the first racially integrated college boards. It took the trustees until mid-July to acquire a home, an 11-story office building on Wells Street, and a lease on a second building on Wabash Avenue for a music school.

The Board then had two months to raise money, remodel offices into classrooms, studios and labs, and plan for fall classes. They bought chairs from Standard Oil, lab equipment from Illinois Technical College, and books, desks and blackboards from a variety of sources. Faculty and students pushed carts piled high with books and supplies through city streets to set up the new campus and worked alongside painters and carpenters to ready the classrooms for the fall semester.

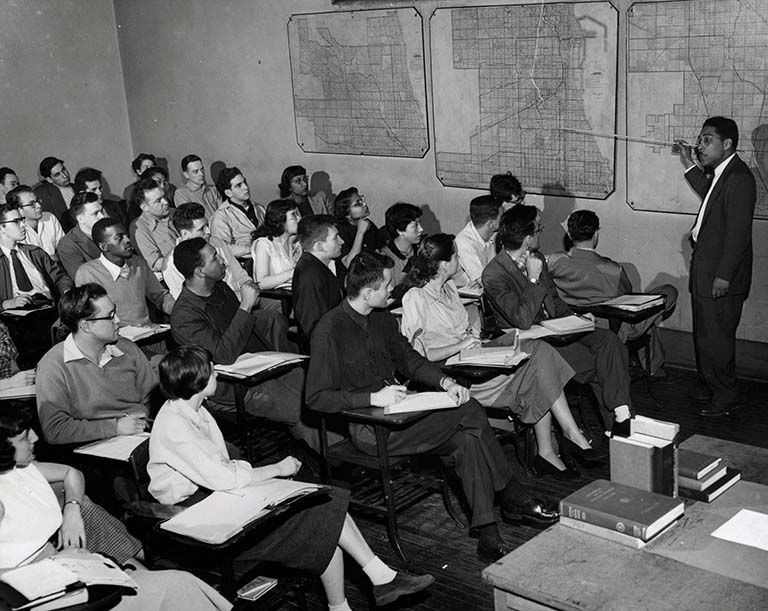

At the same time, Roosevelt College leaders were busy creating one of the most diverse faculties in the United States. In an era when most American professors were white male Protestants, Roosevelt hired men, women, African Americans, Jews, European refugees, Catholics and teachers from India, China and Latin America. Founding faculty included political scientist Tarini Prasad Sinha, sociologist Rose Hum Lee, economist Abba Lerner, philosopher Estelle De Lacey, language professor Dalai Brenes, sociologist St. Clair Drake, chemist Edward Chandler and many more.

The faculty grew to 71 full-time and 90 part-time professors by 1946. An additional 1,000 professors from around the country sent applications hoping to work at this pioneering college, even if it meant a cut in pay.

Approximately 1,200 students began classes on Sept. 24, 1945. They were even more diverse than the faculty – and were described by one newspaper as “Chinese, Japanese, Negroes, Levantines, Jews, Catholics and Down East Yankees.” The next year, realizing the first campus was too small to accommodate the number of students seeking admission, Roosevelt acquired Chicago’s famed Auditorium Building on Michigan Avenue. Five thousand students, from military veterans to new high school graduates, registered for classes in the fall of 1947.

And so a new college began. Magazine and newspaper reporters flocked to the classrooms and marveled at Chicago’s “equality lab.” In November of 1945 Eleanor Roosevelt, chair of Roosevelt’s Advisory Board, dedicated the college “to the enlightenment of the human spirit.” A remarkable act of courage by a college president, staff, faculty and students in the spring of 1945 had created, as one journalist wrote, nothing less than “a model of democracy in higher education.”

Feb. 15, 2017 — I was one of those students, and had some of the instructors listed & shown. Brought back a lot of memories. For several weeks now I have been asking the question of what the President of the Community College I now teach at will do if she is asked to supply such a list — especially where the instructors are concerned.

As one who was born and raised in Chicago, I am proud that Roosevelt University stands as a tribute to the noble spirit that broke down barriers and changed hearts and minds. Your story is a beautiful one of inspiration, courage and sacrifice undertaken with the belief and vision that your transcendent mission would prevail.

Thank you, Roosevelt University, for demonstrating to the world that “Diversity and Inclusion” can transform our world into one where all individuals are valued and all voices heard for the betterment of each of us!