Feminism and fashion are not often considered allies. If feminism is thought to be serious, high-minded and ideological, fashion is considered its very opposite: trivial, superficial and subject to the whims of personal taste. Where feminism concerns itself with ethics, fashion revels in aesthetics. If feminism teaches us to see the deeper forces shaping human experience, fashion directs our eyes outward, to the surface of things.

Feminism and fashion are not often considered allies. If feminism is thought to be serious, high-minded and ideological, fashion is considered its very opposite: trivial, superficial and subject to the whims of personal taste. Where feminism concerns itself with ethics, fashion revels in aesthetics. If feminism teaches us to see the deeper forces shaping human experience, fashion directs our eyes outward, to the surface of things.

Indeed, fashion has long been a favorite target of feminism, which has, over the years, taken aim at trends unfriendly to women’s freedom. Feminism has fought against clothing that limits women’s physical — and thus social — mobility, and styles that demand women wage war on their bodies to achieve an idealized silhouette. But this is not the only way feminism’s relation to fashion plays out. Fashion has been a valuable accessory to feminism as often as its enemy, for as much as fashion may police the body or encourage conformity, fashion is also a powerful vehicle for defiant self-expression and lodging a collective complaint against the status-quo.

Fashion also has an uncanny ability to absorb and repack-age the look of countercultural movements, making them palatable to mainstream consumers and turning a profit in the process. Feminism was part of the very cultural engine that drove the hugely popular “natural look” in women’s cosmetics in the 1970s, directly influenced the “power suit” silhouette in American women’s fashion in the 1980s, and is frequently cited as inspiring the earthy punk of 1990s grunge.

“Fashion has been a valuable accessory to feminism as often as its enemy, for as much as fashion may police the body or encourage conformity, fashion is also a powerful vehicle for defiant self-expression and lodging a collective complaint against the status-quo.”

And fashion continues to be a central preoccupation in current commentary on feminism: The website of a leading feminist organization, the Feminist Majority Foundation, hosts a short video entitled “This Is What a Feminist Looks Like.” The video features men and women of varying ages, races, shapes and styles, each of whom utters for the camera, “This is what a feminist looks like.”

The video contains repeated references to a broad range of fashions and personal styles as compatible with feminism. Actress Christine Lahti tells the viewer, “It doesn’t mean that you hate men . . . it doesn’t mean that you have hairy legs.” Pop singer-songwriter Lisa Loeb smiles into the camera and says, “Sometimes I choose to wear short skirts. Sometimes I choose to wear pants. I don’t think I’m less of a feminist when I wear a super-short skirt.” Contrary to the assumption, then, that feminism stands in opposition to fashion, we have ample evidence that feminism works with fashion as well.

So what can current trends in women’s fashion tell us about feminism’s impact on mainstream culture in general, and women’s lives in particular? In what follows, I’ll make the case that new ways of thinking about women’s identity among contemporary feminists can be revealed through a close look at the trend of mix-and-match fashion.

Contradiction and third-wave feminism

In the 1990s, American feminism announced the onset of its “third wave” with an explosion of writing by young women both influenced by and critical of “second wave” feminism of the 1960s and 1970s. Inspired by the slogan “the personal is political,” so-called second wave feminism is characterized (by its critics, especially) as requiring that women bring their lifestyles into strict obedience to their political ideals to achieve greater ideological consistency. As feminist consciousness prompted women to reconsider their values and choices, feminists worked to reconcile whatever conflicts may have existed between their personal lives — including the choices they made and the values they espoused in love, sex, work, family and leisure — and their outward politics.

Self-identified third wave feminists who came of age following this era expressed skepticism regarding the moral rigidity they perceived in second wave feminism, considering it a set of harsh rules mandating political correctness in all spheres of life, at direct odds with pleasure, personal idiosyncrasy and self-expression. The inner life of the self, they argued, is unruly, chaotic, and made up of multiple, often conflicting elements not easily disciplined or aligned with a single moral code.

Thus, in a break with the perceived severity and inflexibility of an earlier feminism, third wave feminists claimed inner contradiction as women’s essential trait. This emphasis on contradiction appears repeatedly in some of the most popular feminist texts from the past two decades, most notably in Rebecca Walker’s To Be Real; Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera, and Susan J. Douglas’s Where the Girls Are, in which she describes American women as a “bundle of contradictions” and explicitly links contradiction to feminism by observing that “contradictions and ambivalence are at the heart of what it means to be a feminist.”

In the same spirit, Donna Haraway’s classic essay of postmodern feminism, “A Manifesto for Cyborgs,” describes the female self as a figure of collage and hybridity, “a kind of disassembled and reassembled … self. This,” Haraway asserts, “is the self feminists must code.”

The fashion of contradiction

Feminists have coded this self so effectively in recent years that the notion of the contemporary American female self as a collage of contradictory bits and pieces has been absorbed into mainstream popular fashion trends and conceptions of personal style.

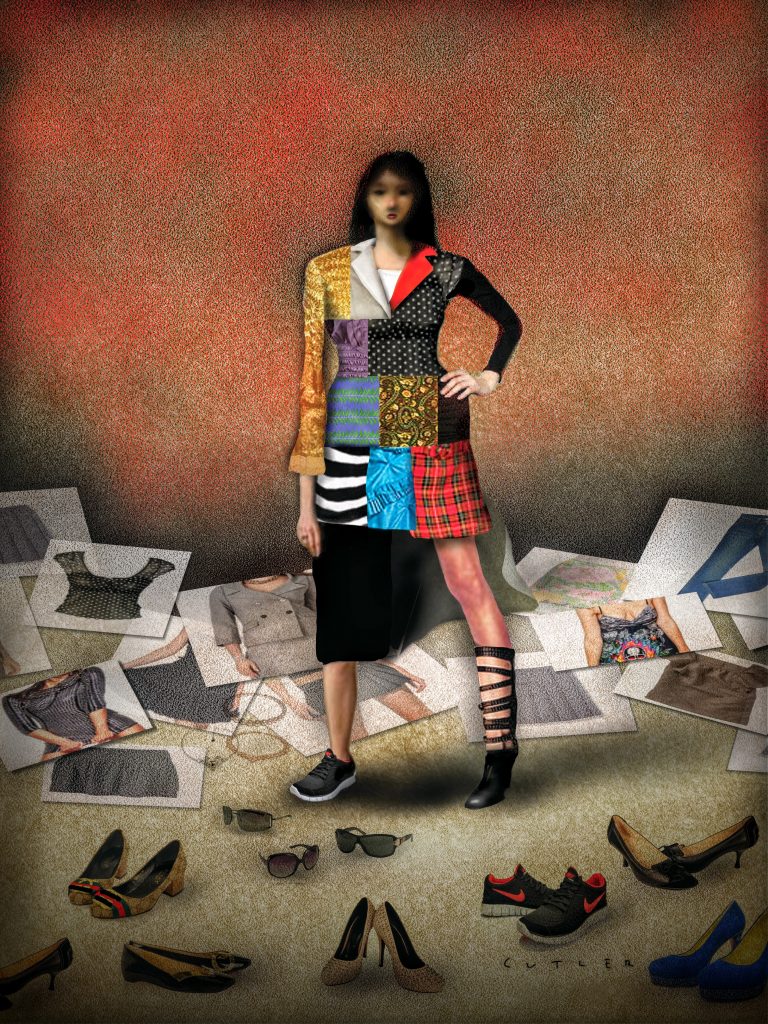

The self whom third wave feminists describe as having contradiction at her core expresses this internal chaos vividly in the hugely popular trend of mix-and-match fashion.

While mixing and matching has a rich history as a sartorial strategy ever since the advent of separates in the early 20th century — historically, it has served both utilitarian and subcultural goals, and has long been celebrated as a way to stretch one’s wardrobe in hard economic times. I focus here on a distinctive, early 21st century revival of a mix-and-match aesthetic in American mainstream women’s fashion, described by fashion journalist Anita Leclerc as a “parade of patterns (that is) like watching seven rival marching bands converge at a four-way intersection — talk about your clash of symbols.”

“Feminists have coded this self so effectively in recent years that the notion of the contemporary American female self as a collage of contradictory bits and pieces has been absorbed into mainstream popular fashion trends and conceptions of personal style.”

This latest iteration of mix-and-match fashion takes as its goal something other than utility or wardrobe-stretching, appearing instead to serve the rhetorical purpose of announcing the wearer’s contradictory nature. Through a style of deliberately clashing patterns, textures and references to different fashion eras at once, the contemporary American woman visually comments on her hybridized, indefinable inner self through juxtapositions of formerly unmixable, unmatchable styles.

This trend stands in stark contrast to earlier ways women and girls were instructed to dress. If they were once encouraged to cultivate one look to express their identity, girls and women now show their fashion savvy by coming up with unlikely combinations of styles worn together, suggesting a preference for multiplicity over a singular look or a singular identity. In a feature called “Best Dressed Girls in America,” Seventeen magazine selected a small group of readers who exemplify what the feature editor calls “bold style.” Eight out of the 17 girls featured describe their personal style as some form of deliberate collage, using words like “eclectic,” “eccentric,” “odd and experimental,” and “a little bit of everything.” Catherine from New Orleans, aged 13, describes her personal style as “edgy punk mixed with glam prep;” Tory from Concord, Mass., age 15, calls her personal style “’60s mod and ’70s boho.”

This trend stands in stark contrast to earlier ways women and girls were instructed to dress. If they were once encouraged to cultivate one look to express their identity, girls and women now show their fashion savvy by coming up with unlikely combinations of styles worn together, suggesting a preference for multiplicity over a singular look or a singular identity. In a feature called “Best Dressed Girls in America,” Seventeen magazine selected a small group of readers who exemplify what the feature editor calls “bold style.” Eight out of the 17 girls featured describe their personal style as some form of deliberate collage, using words like “eclectic,” “eccentric,” “odd and experimental,” and “a little bit of everything.” Catherine from New Orleans, aged 13, describes her personal style as “edgy punk mixed with glam prep;” Tory from Concord, Mass., age 15, calls her personal style “’60s mod and ’70s boho.”

In the “Looks” column in BUST magazine, the featured fashionable feminist Cynara Geissler describes her fashion sense as “pull[ed] from a lot of seemingly disparate places. There’s a lot of tough, Springsteen, working-class stuff going on and also a Claudia Kishi from The Baby-sitter’s Club kind of whimsicality.” One gets the sense that it is downright unfashionable to claim allegiance to a stable fashion style or a stable female identity, in clear contrast to the ideologies of past generations, where expressing ideological consistency was more culturally valued.

In the “Looks” column in BUST magazine, the featured fashionable feminist Cynara Geissler describes her fashion sense as “pull[ed] from a lot of seemingly disparate places. There’s a lot of tough, Springsteen, working-class stuff going on and also a Claudia Kishi from The Baby-sitter’s Club kind of whimsicality.” One gets the sense that it is downright unfashionable to claim allegiance to a stable fashion style or a stable female identity, in clear contrast to the ideologies of past generations, where expressing ideological consistency was more culturally valued.

This trend is not simply a result of the consumer’s own creative take, do-it-yourself-style, on the contents of her closet; the message that a clashing mix-and-match style best captures the mood of today’s woman comes from the top corporate brass, too.

Jenna Lyon, creative director for American retailer J. Crew, says she is “obsessed with unexpected pairings” in the company’s collection from last year. When British retail phenomenon Topshop opened its flagship American boutique in New York City, its promotional press materials defined the signature Topshop look as a clash of mix-and-match. Top-shop style adviser Daniela Gutmann promises that “[w]e’re not judging anybody. It’s O.K. if you want to wear a million prints at a time,” while style advisor Gemma Caplan confesses, “[s]ometimes I feel like being all girly and cutesy, sometimes I feel like being rocky.” The Style Advisor tip on Topshop’s website for last year’s winter collection instructs shoppers to “clash your silhouettes to create a show-stopping look.”

“If mix-and-match skill is currently thought to be the essence of a woman’s personal style, then we might rightly wonder whether we expect women to perform a similarly dizzying balancing act in their lives more generally.”

On the national scene, the mix-and-matcher par excellence is Michelle Obama. Praised for her talent at mixing high and low, classic and trendy, and strong and soft, the First Lady is considered to have an exceptional sense of style that relies on quirky clashing.

Some of her most editorialized fashion choices to date are those that emphasize unlikely combinations: a girlish white cotton blouse with an exaggerated bow at the neck cinched with a black, metal-studded leather belt — equal parts frill and punk. Or a standard Washington look with a twist: a conservative twinset and delicate pearl choker offset with an oversized, clashing silver metallic belt, described by one fashion editor as “a busy ensemble.” To her fans, the very appeal of her look is in its purposeful assemblage of multiple fashion references.

At the 2009 Council of Fashion Designers of America awards ceremony, Mrs. Obama received the Board of Directors Special Tribute in recognition of her distinctive style, described by council president Diane von Furstenberg as “a unique look that balances the duality of her lives,” referring to the multiple roles the First Lady plays in both public and private. This statement invokes the notion of a multiple female self so familiar to contemporary feminists, suggest-ing the impact of feminist thought on more mainstream, popular notions of female identity.

Indeed, in descriptions of her life (and lifestyle) in the White House, Michelle Obama is repeatedly described in rhetoric celebrating her ability to inhabit multiple roles. In an interview, Katie Couric describes Mrs. Obama as “this Harvard-educated lawyer and former executive, digging up sweet potatoes on the back lawn of the White House,” and “She’s Michelle … great-great-great-granddaughter of a slave … Michelle the devoted mom … Michelle the wife of Barack … Michelle the glamorous style icon … Michelle the political player.”

This conception of Michelle Obama as having so many component parts — some of them potentially in conflict with each other — is mirrored in coverage of her personal style. Obama herself acknowledges this is her trademark look, describing her fashion sense in her June 2008 appearance on The View as “I do a little bit of everything.”

If Michelle Obama offers a highly visible image of an American woman successfully balancing a multiplicity of roles and styles, Carrie Bradshaw is the figure who aspires to it in the popular imagination.

Compare Carrie, whose fashion sense is defined by its very refusal to be defined, with the other members of her famous four-some: Miranda, a caricature of a single-minded “career woman” who dresses in staid, often severe clothing; Charlotte, whose childlike innocence is mirrored in her modest, girlish fashion sense; and Samantha, a sexual adventurer whose clothing is always body-conscious and often borderline garish.

Against the backdrop of these three stock character types, the distinctive trait of Carrie, the protagonist of the Sex and the City franchise, is her elusive, contradictory nature and profound ambivalence toward ideologies of American womanhood. She eschews yet craves marriage, is cynical yet hopeful about romance, and adamant yet anxious about self-sufficiency.

Carrie personifies a cultural moment in which cultural expectations of women are in flux, and this flux is the essence of Carrie’s cacophonous fashion sense, a signature look described by the scholars Stella Bruzzi and Pamela Church Gibson as a “violent yoking together of clashing sartorial styles” featuring the most unlikely combinations of garments, silhouettes and accessories that add up to a vision of deliberate discordance, such as a newsboy cap paired with hot pants, a trench coat and haute couture heels.

As a fictional meditation on late-20th-century feminism, Carrie’s expression of contradiction plays in a different, more anguished register than Michelle Obama’s: where the First Lady exudes confidence in achieving the feminist promise of “having it all” (and, it is worth noting that she has a network of support helping her do so), Carrie exudes insecurity, often stumbling to manage her personal life and consistently confused about what, exactly, will fulfill her.

Is contradiction worth celebrating?

If fashion tells us what a culture thinks about itself, then we may conclude that the trend of mix-and-match in women’s fashion reveals the impact feminism — long considered anti-fashion and certainly not in the cultural mainstream — has had on popular notions of American women, their identities and their choices.

If fashion tells us what a culture thinks about itself, then we may conclude that the trend of mix-and-match in women’s fashion reveals the impact feminism — long considered anti-fashion and certainly not in the cultural mainstream — has had on popular notions of American women, their identities and their choices.

In addition to demonstrating what a culture finds appealing about women, fashion trends may also suggest what is socially required of women in a given cultural moment, leaving us to con-sider whether contradiction deserves to be celebrated or lamented as a feature of contemporary life.

If mix-and-match skill is currently thought to be the essence of a woman’s personal style, then we might rightly wonder whether we expect women to perform a similarly dizzying balancing act in their lives more generally, and whether a cultural imperative that women “multi-task” (and like it!) is unconsciously reinforced through a mix-and-match aesthetic. For if we only celebrate the multiplicity of women’s lives, we fail to examine the particular social conditions under which those lives are forced to take on their multiplicity — and thus fail to consider whether “having it all” is a privilege or a burden.

If mix-and-match skill is currently thought to be the essence of a woman’s personal style, then we might rightly wonder whether we expect women to perform a similarly dizzying balancing act in their lives more generally, and whether a cultural imperative that women “multi-task” (and like it!) is unconsciously reinforced through a mix-and-match aesthetic. For if we only celebrate the multiplicity of women’s lives, we fail to examine the particular social conditions under which those lives are forced to take on their multiplicity — and thus fail to consider whether “having it all” is a privilege or a burden.

One thought on “[Summer 2011] Fashion forward?”