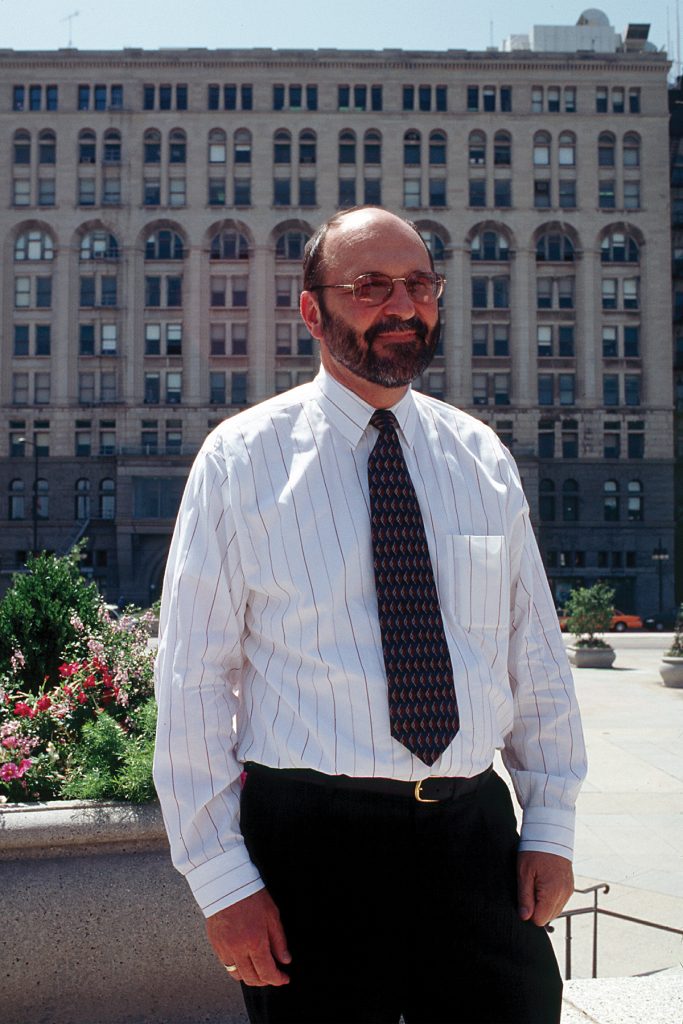

Charles “Chuck” Middleton will retire as President of Roosevelt University on June 30, concluding a career in higher education that has spanned five decades.

When Middleton attended graduate school at Duke University in 1965, his goal was to become a professor. Little did he know that he would advance up every major rung on the higher education ladder. In addition to being president of Roosevelt since 2002, he was a history professor and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Colorado at Boulder, provost and vice president for academic affairs at Bowling Green State University and vice chancellor for academic affairs at the University System of Maryland.

An expert on modern British history from the late 18th Century to the early 19th Century, Middleton believes deeply in academic scholarship and in preparing students to become contributing members of society. He has a national perspective on higher education honed by taking active roles in organizations like the American Council on Education that are at the forefront of major issues affecting postsecondary education.

In an interview this winter with Roosevelt Review Editor Tom Karow, Middleton reflected on his career and the changes taking place in higher education.

Q: What are the biggest changes in higher education you have observed during the past 50 years?

A:“What’s the same” is a quicker question to answer. The biggest change for me is that higher education is facing far greater accountability, far more institutional supervision and far more reporting than ever. There’s much more scrutiny of higher education institutions, not just overall, but down into all levels of operation. This level of compliance and accountability would have been unimaginable in the first 15 to 20 years of my career. While intentions might be good, when regulations affect the quality of institutional operations, they become intrusive and impinge on the ability of people to go about their work effectively. And they increase cost.

Q: Why are governmental regulations increasing?

A: I think it’s a reflection of the level of government investment these days. Federal and state governments want to be sure they’re getting a good return on their investment and that means greater accountability. I think oversight is going to become even more intense, requiring universities to spend more time on providing thoughtful and reasonable responses to issues as they emerge. This is a national challenge that presidents around the country are addressing.

Q: In order to remain in higher education for such a long time, you must enjoy being with young people.

A: As I like to tell my 92-year-old mother, I have been with 18-year-olds, year in and year out, ever since I was one. I love being surrounded by these energetic, enthusiastic, inquisitive, smart people who are yet to be fully shaped by life. It’s a unique opportunity we have as faculty and staff to change and mold these students to look at the world in new ways.

“For me, in the end it’s all about students. That’s one of the most rewarding parts of the job and the thing I will miss most.”

Chuck Middleton

Q: Do you notice dramatic differences between freshmen and seniors?

A: The freshman year is probably the most transformational period of time in most students’ lives. It’s a scary time, too, as all students wonder if they will be successful in college. By the time students are seniors, they’re more completely rounded young adults able to do things and think in ways that they couldn’t do or think just four years earlier, and they are far more self-assured.

Q: You have worked in both public and private universities. How can students decide which school is best for them?

A: I think students should go to the college or university that best suits their personal, intellectual and career goals. For many undergraduates, the best education is actually not at the most prestigious institution. Students should consider a school that offers more interaction with faculty and allows them to meet other students like themselves. The quality of the faculty and classes are fundamentally going to be largely similar everywhere. So it depends a lot on comfort level and the ability to engage people in your own peer group, people who are interesting and challenging to you.

Q: Do you think higher education has become more for the haves than the have-nots?

A: I think opportunities are more extensive than ever. Compared to when I went to college, there are more choices both for institution and for degree options. This means that for every student, there is likely to be an optimal college or university where they can grow, be nurtured and be challenged to do well. The key is to find it. That said, I also think that if you look at the cost of higher education as a function of not just what you spend, or how much you borrow, but also how long it takes you to get through and into the job market, those with wealth have a leg up because on average they have to work less while in school.

Q: How should higher education be funded?

A: Higher education is a public good because it is important, indeed vital, for our country to have large numbers of its citizens well-educated. Because this is so, it is imperative that we collectively invest in it and invest in it at very significant levels so that everybody has an opportunity to go, irrespective of their background.

Q: Can you discuss the importance of a choosing a major when you are a freshman?

A: I think that when you’re 35, which to 18-year olds is twice their life, what you’re doing hardly depends on the technical skills you learned in college. Your success will depend on whether you can think, work hard and be reliable – things that you learned in college because if you didn’t, you flunked. Students who are passionate about professional fields should major in them, but if you would rather be a poet as an undergraduate, do that. The key thing is to exercise your mind so that it is resilient and continues to grow, whatever you wind up doing for a job or career.

Q: Which part of your career have you enjoyed most?

A: Oh, I love the presidency. It’s by far better than any other position. As the president, you have the ability to set the tone for the institution and to respond to the best of your ability to the aspirations and hopes of all the people within it. There isn’t any issue, any university constituency that you’re not concerned with. You are responsible for the maximum success of the university, which I define as the individual and collective successes of the students and the employees within it.

(Left) Middleton shakes the hand of every graduate at every Commencement ceremony. (Top) Middleton was the driving force behind returning men’s intercollegiate athletics to Roosevelt and starting a woman’s sports program; (Bottom) Talking with James Mitchell III, who was chair of the Board of Trustees during Middleton’s entire tenure as president.

Q: Has your opinion of the presidency changed during your tenure at Roosevelt?

A: This is my 13th year as President. That’s twice the national average, so it’s like serving two successive average presidencies. I will tell you that the job today at Roosevelt is not the job I was hired to do in 2002. It is far more difficult, far more complex, far more subject to external forces than it’s ever been.

“Opportunities are embedded within change, so you need to be adaptive and responsive in order to take advantage of what lies ahead.”

Chuck Middleton

Q: Why do you think the average university president only stays in the job for 6.5 years?

A: There are two answers to that. For starters, I think these jobs are almost undoable at some level. This is because often too much is expected of the president. There’s less tolerance when the president doesn’t instantly do what the community wants. Presidents are pulled and tugged in essentially every direction simultaneously by somebody or some group. The other reason is that people burn out in the job. The number of days that you don’t engage with your institution and its issues over the course of the year is exactly zero. Even on major holidays, on vacations, you’re on your computer attending to the issues of the institution. It takes high levels of energy and constant attention to taking care of yourself as well if you are to be effective.

Q: Can you give an example of a challenge you’ve been facing?

A: One of the biggest challenges is getting the Roosevelt community to seriously focus on institutional change. People are so concerned with their own jobs and careers that they don’t always look ahead. Although we can’t always predict what’s coming, we do know that things are not going to be as they were in the past. Opportunities are embedded within change, so you need to be adaptive and responsive in order to take advantage of what lies ahead. And fearless. Unlike most other types of organizations, higher education is very ill-equipped to handle change.

Q: In your opinion, what’s the ideal background for a university president?

A: Presidents ought to be successful academic people who have extensive experience with teaching, writing, scholarship, advising, promotions, tenure and the like. Being a dean is also valuable because you are the CEO of a college and have to preside over it. It’s also useful to have been a provost because you were able to observe the president and discuss university-wide issues. But I think all successful university presidents, whatever their background, must have a temperament that allows them to be purposeful and aspirational for their institution as their first priority.

(Left) Construction on the 32-story Wabash Building had just begun when this picture was taken; (Right)Visiting with former Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley after the opening of the Wabash Building; (Bottom) At the grand opening of the Lillian and Larry Goodman Center with benefactor Larry Goodman.

Q: What have you enjoyed most about being president?

A: The interaction with students. For me, in the end it’s all about students. As president, you meet students in ways that are different from the experience of others. I have developed a really good rapport with a number of students and I have maintained contact with many of them as alumni sometimes decades after they graduated. For me, that’s one of the most rewarding parts of the job and the thing I will miss most.

Q: What is something else that you really enjoyed?

A: I’ve taken great pleasure in building a much stronger faculty than we had when I arrived at Roosevelt. We increased the number of full-time faculty by 23 percent and we hired terrific new teachers and scholars. They were recruited from top universities across the country. Roosevelt has a great story and is an ideal place for new professors who want to build their careers. I’m very proud of our faculty.

Q: Have you mentored leaders of other universities?

A: There are now six sitting university presidents who have worked with me during my career. At Roosevelt, all three of my former provosts are presidents today. There are other examples I could share but basically I think presidents have an obligation to help prepare younger folks for leadership positions.

Congratulating former Provost James Gandre on Gandre’s installation as president of the Manhattan School of Music.

Q: When you joined Roosevelt, you were one of the first openly gay university presidents. Can you talk about that?

A: I was actually the first openly gay male president though there was one lesbian. Now there are over 60 of us. In 13 years, that change is reflective of the great transformation of American society on LGBT issues. I think in the long run, it’s very healthy because it’s about American inclusiveness at a fundamental level. Being a gay person makes me acutely aware of what it’s like to be marginalized and discriminated against. It’s remarkable how instinctively cautious you remain on personal matters, even when you don’t have to be anymore, because you learned early in your life that a false step has potentially bad consequences for you personally as well as professionally. It’s a great credit to the Roosevelt Board of Trustees back in 2002 that they were willing to hire me, because they were breaking new ground. I think my presence has opened up possibilities for other LGBT people here to be themselves and that certainly has made them more effective in whatever they do.

Q: What do you plan to do in retirement?

A: I really don’t know, but I certainly am not going to just sit still. I love to travel and I am also talking to people who have asked me to consider doing some really interesting work, not all in higher education. One thing’s for sure, it will be nice not to have to be responsible for anybody but my partner John and myself for a while.