This weekend I’m at Santa Clara University in California’s Silicon Valley at one of my favorite professional conferences: the annual gathering of the Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences. Like the literature and environmental folks I hang out with at ASLE‘s biannual conferences, these folks in AESS are my professional tribe: educators, students, writers, scientists, and activists working on every conceivable kind of issue or project related to environmental education and sustainability. (In fact, I’m struck by how pervasive a theme sustainability has become at the AESS conferences, despite the fact that it is not explicitly a part of the organization’s name or identity).

This morning I’m part of a presentation panel entitled “Ethics of Place in Urban Areas,” which was organized by my colleague and friend Gavin Van Horn of the Center for Humans and Nature in Chicago. Here he describes the context, themes, and over-arching issues our panel addresses:

Place has become a topic of increasing scholarly attention and research. Place is particularly relevant to environmental studies and environmental sciences, because place provides a spatial anchor of memory and meaning in which care for the natural world is fostered. Most work in moral philosophy and Western ethics is abstract in the sense that it seeks to discover standards of right and wrong that are universally valid and applicable. Paradoxically, moral psychology tells us that ethical thinking and our sense of value are rooted in the lived experience in a specific place, with specific natural and social characteristics, landscapes, and cultures. The session panelists submit that an ethics of place which roots our ethical obligations more concretely and locally is essential for a more robust environmental future. We examine the ways in which ethics might be re-envisioned to include a respect for complexity and multiplicity of place in an urban context.

Our presentations integrate urban agriculture and alternative economies, landscape aesthetics, urban water quality, environmental education, and the ethics of care to discuss the ways in which place can inform an ecological ethic that is democratic and participatory in its orientation. Our approach is rooted in the disciplines of geography, political science and bioethics, religious studies and ethics, urban ecology, and sustainability studies. While addressing conceptual and ideological questions about the ethics of place, we profile on-the-ground case studies and relevant research from each panelist’s community-based work. Our goal is to engage audience members in a dialogue about how scholars and citizens can better understand how to cultivate respect for and engagement with nature in metropolitan areas – spaces frequently misunderstood as un-conducive to an ethics of place.

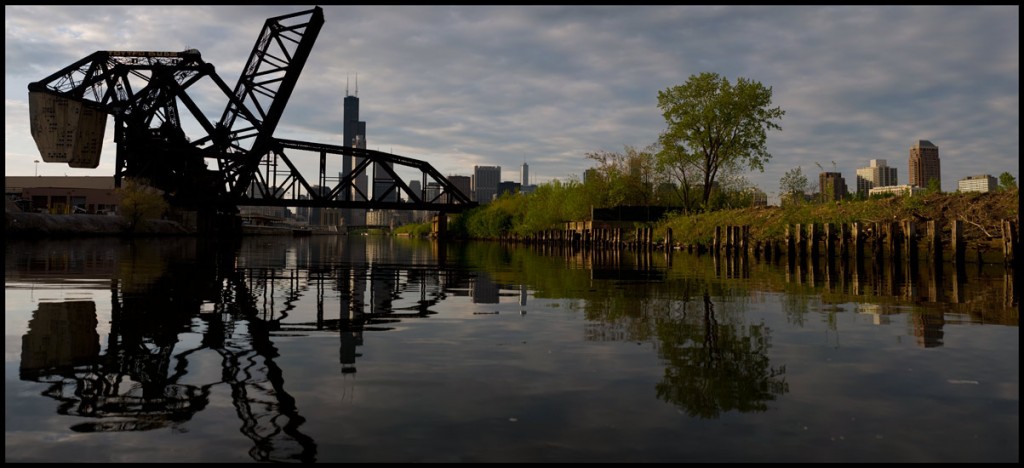

Photo by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee (2010)

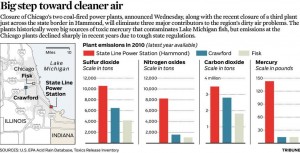

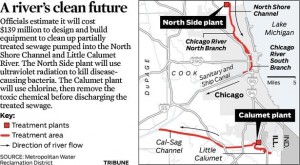

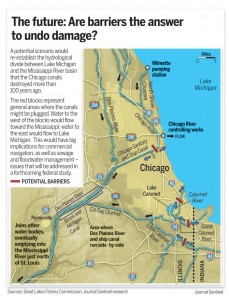

My presentation, “Exploring the Chicago River: Ethics, Sustainability, and a Sense of Place” (view pdf of slideshow) looks at this waterway/ecosystem as one key manifestation of urban nature in Chicago. I explore how scientific and artistic engagement with the river can contribute to one’s sense of not just the river’s history, ecology, and identity, but also that of Chicago in particular and watersheds more generally. As my abstract notes,

The degraded yet undeniably charismatic urban waterway, the Chicago River, is a mighty fine place to contemplate the tangled relationships among water quality, land use, and sustainability within cities and suburbs. As a site for exploring urban nature, an object of analysis in the scientific assessment of water quality and urban ecology, and a case-study in landscape aesthetics, the Chicago river provides students and citizens myriad opportunities to develop a sense of place. More generally, experiencing urban rivers — and understanding their function within the complex watersheds of metropolitan regions — can foster not just ecological literacy about urban ecosystems but also ethical engagement with one’s community.

You can also view a Powerpoint slideshow of my presentation (here with annotations) that features several photographs of the river by Ryan Hodgson-Rigsbee, who collaborated with me on a Mindful Metropolis cover story about the Chicago River back in 2010. Read more about rivers here on this blog, as well.