Every semester I take my Roosevelt University undergraduate students on field trips — hands-on learning experiences that allow us to put some of the academic ideas we’ve studied into practice, work together in teams, and create a sense of community. That’s especially important in online classes, where virtual interaction is intense and sustained, but face to face action is rare or nonexistent.

This fall at RU’s Schaumburg Campus, my Sustainability Studies 220 Water course’s hybrid format (a combination of occasional Saturday sessions plus weekly online interaction) is ideal for scheduling field trips to likely sites of interest. Normally I would wait until one-third of the way through the semester before venturing on a trip with a group of students — but since SUST 220 had a long Saturday campus session to kick off the semester and early September is usually a good time to be outside in the Chicago area, we decided to get right to it.

So after two hours of morning lecture and discussion on September 10th and meeting each other for the first time, my students and I enjoyed a picnic lunch in the campus courtyard and then headed over to Busse Woods, one of the largest holdings within the Cook County Forest Preserve system (at 3,700 acres), for field-based introduction to water quality sampling techniques.

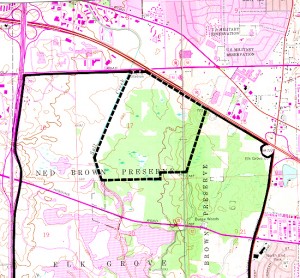

Busse Woods, aka the Ned Brown Forest Preserve, is a massive and multi-functional piece of green infrastructure in the northwest suburban region, a culturally significant recreation site for the many communities it serves, and a fascinatingly complex mosaic of northern Illinois ecosystems — riverine, woodland, wetland, and prairie. The preserve directly borders the suburbs of Rolling Meadows, Arlington Heights, Elk Grove Village, and Schaumburg; but within a short drive or even bike ride are numerous other communities, including Palatine, Prospect Heights, Mount Prospect, Des Plaines, Wood Dale, Itasca, Roselle, Hoffman Estates, and Inverness. People in these suburbs and beyond converge on Busse Woods year-round to boat, bike, hike, rollerblade, picnic, fly model airplanes, visit the elk herd (yes, elk!), and more, making it one of the most-heavily used forest preserve units in Cook County. Fortunately, the preserve’s sheer size and diverse offerings of groves, parking areas, meadows, and trails enable it to accommodate all this activity and still provide much needed open space for the region and the chance of someone to roam within an extensive natural area. The Cook County Forest Preserve and the Friends of Busse Woods actively work on conservation and restoration projects in the preserve.

Just to the southeast is O’Hare Airport, which at approximately the same size as the preserve represents a completely different way of using land — the concrete and asphalt “hardscape” of O’Hare strongly contrasts with the verdant landscape of Busse Woods. Besides recreational opportunities and open space for its human visitors, Busse harbors a significant amount of regional biodiversity:

the 440-acre Busse Forest Nature Preserve, located in the northeast section of the Forest Preserve unit, is not only a state-designed nature preserve (the third one so dedicated, in 1965) but also a National Natural Landmark. This protected area harbors bottomland flatwoods, extensive wetlands, and upland forest, some of which are in the process of restoration.

Busse Woods is home to a couple of significant water features including Salt Creek, which was the first stop on our trip. After hiking through a forest-and-wetland path along the northern border of the woods, we came to the Golf Road overpass of Salt Creek, where the river south into the preserve before it empties into Busse Lake, a sprawling artificial reservoir created by a dam structure at the south end of the preserve. Using a couple of different water quality field testing kits, we sampled the creek and measured a range of physical/chemical water quality indicators: chlorine, copper, dissolved oxygen, hardness, iron, nitrate, pH (acidity), phosphate, temperature, turbidity, and total coliform bacteria. In doing so, we not only took the ecological pulse of Salt Creek at one point in time, we also learned how to use our sampling equipment, compared test results from different measurement procedures, assessed the possible sources of error in our data collection, and analyzed the impact of the surrounding landscape upon the water quality of Salt Creek.

You can see our tabulated results here: Water Quality Data and Results for Salt Creek and Busse Lake 10 Sept 2011 (pdf).

The entire Busse Woods preserve is a significant green space within the Salt Creek Upper Watershed, as it receives stormwater run-off from the eastern half of Schaumburg via the main channel of Salt Creek as well as the Creek’s West Branch. That tributary is important for another reason, as it flows through the heart of Schaumburg before passing around the periphery of the John Egan Wastewater Treatment plant of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District.

The Egan plant’s treated effluent is piped into the West Branch, which then flows east under I-290 to empty into the South Pool of Busse Reservoir. Partly for that reason, we chose to sample water from the shoreline of the South Pool as our second sampling site of the day. (Interestingly, the data from that site were quite comparable to those we gathered much farther north at Salt Creek.)

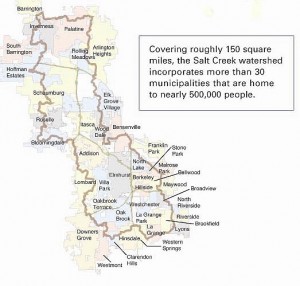

In this sense, then, Busse Lake is a giant detention pond for stormwater run-off from several suburban communities (either directly or via Salt Creek) and treated wastewater from Schaumburg. As such, it is a flood control structure for Salt Creek, which runs south/southeast out of the preserve and drains several western suburban communities before joining the Des Plaines River near Brookfield.

Effective water retention in Busse Lake means reduced flooding in downstream communities, though the persistence of flooding in the western suburbs means the reservoir as currently configured is only a partial solution. Nevertheless, the larger forest preserve complex of wetlands, prairies, and woodlands — of which the lake is but a part — act like a giant sponge for the surrounding towns and villages, absorbing precipitation and run-off from a wide area and releasing it slowly to the atmosphere and to Salt Creek.

In short, Busse Woods are a vital component of the hydro-ecology of the Upper Salt Creek Watershed. In turn, as a stream that winds through a score of suburban communities and which is a major tributary of the Des Plaines River, Salt Creek is a waterway that displays the impacts of urbanization on natural systems, even as it provides vital green space for half a million citizens in the Chicago area. It’s also an ideal ecosystem in which to explore and assess the need for sustainable water management as a means of improving the quality of our region’s surface waters and minimizing the risk of pollution and flooding within the watershed.