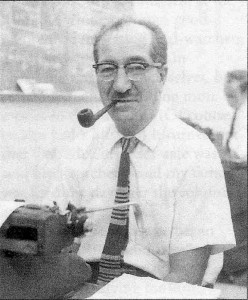

Leonard Dubkin (1905-1972) was a businessman, journalist, naturalist, and nature writer who lived and worked in Chicago.A contemporary of the much more well-known Nelson Algren and Studs Terkel, Dubkin is a long-neglected urban nature writer of the 20th century whose journalism and books provide a unique and fascinating window into Chicago’s environmental history and urban landscape during a period of immense social and biological change in America’s cities.

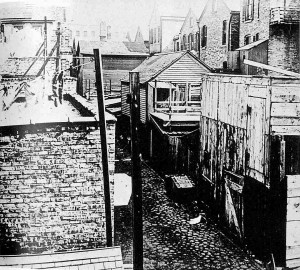

Dubkin’s life was both humble and extraordinary, rife with early obstacles and replete with fascinating episodes worthy of a melodramatic up-from-his-bootstraps narrative. His early years were marked by poverty and a dogged determination to make something of himself. Dubkin was born in Odessa, Russia, in 1905; his family emigrated soon thereafter to the United States and in 1907 they settled on the near West Side of Chicago, an area of the city that served as a portal for Jewish immigrants, particularly those of Eastern-European ancestry. One of seven children and the oldest boy of the family, young Leonard cultivated an interest in the natural world from the time he was nine years old, and spent a great deal of time exploring various neighborhoods in the city in search of birds, insects, and other wild creatures in the scraps of natural areas within the urban environment he would later recall as some of his “secret places.”[i]

Dubkin’s family knew poverty on a daily basis during his early years in Chicago, as did many in their tenement neighborhood characterized by overcrowding and economic hardship. Dubkin’s father was chronically ill with lead poisoning from his work as a housepainter in Russia, and was unable to work during his time in Chicago; his mother kept the family going by taking in sewing work and accepting the help of local Jewish charities. Though he left school before finishing eighth grade so he could work to help support his family, Dubkin nevertheless kept collecting animal specimens, exploring out-of-the-way pockets of urban nature, writing down his observations in a journal, and cultivating an ambition to become a naturalist. He also fought his own battle with a debilitating illness: around the age of 15, he contracted encephalitis and lapsed into a coma that lasted almost a year during which he resided at a sanitarium in nearby Winfield, Illinois. Awakening suddenly to the surprise of doctors and delight of his family, Dubkin built up his strength during a long recovery period by playing tennis — and such was his athleticism that he soon became a ranked player in the city public leagues.

From childhood onward, Dubkin worked a variety of jobs — from cleaning out taverns to driving a cab to starting his own businesses — to support himself and his family, and though a modest and relatively unassuming person in general, he possessed an undeniably entrepreneurial spirit. As a young man and aspiring author determined, in rather romantic fashion, to cultivate the attitude and garner the life experiences he felt were necessary to a writer, he left Chicago and traveled around the country by riding the rails, hobo-style. When he ran short of money, he would stop at a city of some size and drum up work as a reporter for one of the local papers for awhile, before catching another freight train for different pastures. In this way over a period of perhaps two years or so, he wrote briefly for papers such as the Times-Picayune in New Orleans and the Sacramento Bee, honing his journalism skills and soaking up impressions of different places and people. After his return to Chicago, he made the city his home the remainder of his life, despite the fact that his mother and six siblings all relocated to Los Angeles.

Dubkin once lost a job as Chicago Daily News reporter after blowing an assignment to cover a murder story (itself a fascinating and humorous anecdote he would later recount as the “Racine Case” in his two of his books) by watching squirrels in the attic of the primary suspect’s home while the latter returned to the scene of the crime and was caught by police. Ironically, he claimed to be grateful for being set free, as writing about human affairs bored him in comparison to his passion for chronicling the activities of the natural world. Yet the demands of paying the rent kept him hustling after work even as he nurtured his artistic inclinations and fascination with nature. After several months of fruitlessly searching for newspaper work, he started a one-man public relations firm which lasted a few years, and it was through his publicity work for a local radio station that he met actress and his future wife, Muriel Schwartz, at a radio industry party. During the early years of the Great Depression, he capitalized on (and further cemented) his intimate knowledge of Chicago’s streets and neighborhoods by working as a cab driver. In the 1930s, he started yet another business enterprise: a talent directory of Chicago stage and radio actors, which he updated and published yearly up through the mid-1950s.

Finally, from the late ’50s onward, he worked full-time as a reporter and columnist for Lerner Newspapers, which produced a diverse offering of neighborhood weeklies for various Chicago neighborhoods. This great variety of experiences and jobs exemplifies not just his industriousness and entrepreneurship, but also the scope and depth of his creative energies. While his day jobs limited his natural history and creative writing activities to being after-hours pursuits rather than his primary focus, they provided him a measure of middle-class economic stability and even supplied him with a narrative theme he would explore in several books — the ongoing tension between the impulse to observe and commune with urban nature and the demands of earning a living in modern America.

As his keeping of a childhood nature journal indicates, Dubkin carved out an early identity as a naturalist-writer, and his facility with language earned him a journalism gig as a young teenager when he started writing a weekly nature column in the Saturday children’s page of the Chicago Daily News. Not only did this employment eventually lead to life-long work in journalism as a reporter, columnist, and urban naturalist, it provided the occasion for a transformative meeting between young Dubkin and one of Chicago’s greatest historical figures. As Dubkin recounts, he would take his handwritten drafts to nearby Hull House to type them up, for the staff allowed him to use their office equipment. When one of these times the “head lady” asked him what he was working on, he stunned her by replying he was typing up his articles for the Daily News and showed her a copy of his latest column which he happened to have in his pocket for just such an auspicious occasion.

She read my article, which was about migratory instinct in birds. “Do you always write about nature?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, “I’m going to be a naturalist when I grow up.”

“Don’t you think you need a typewriter to be a naturalist?”

“Sure I do. And some day I’m going to be able to afford to buy one.”

She asked me where I lived, and after I told her she walked away. A few days later a man delivered a package to our house, addressed to me. Inside was a brand new typewriter from the kind lady at Hull House. Her name was Jane Addams. (My Secret Places 17)

Because his formal education was cut short, Dubkin never became a professional scientist as he once fantasized; instead of fretting over this missed opportunity, though, he transformed it into a narrative theme. His writings are peppered with amusing encounters between himself, as the amateur naturalist/narrator, and professional scientists from Chicago-area institutions. The contrasts he drew between the two perspectives illustrate not just his respect for (and, to some degree, insecurity about) the authority of science as arbiter of knowledge, but also his view that institutionalized science could be cold and detached.

Nevertheless, Dubkin was as much enthralled by science as he was by nature itself, and from an early age steeped himself in the writings of naturalists from Darwin to Ernest Thompson Seton. He also held scientists such as Darwin, Mendel, and Einstein in the highest regard — not just for their technical acumen and writing ability, but for their ability to think critically and experimentally, to “come to . . . [nature] with a question, with just the right question, and who have the kind of minds that know how to go about getting an answer” (Natural History of a Yard 55). Consequently, Dubkin always grounded his observations of the natural world in his extensive reading of both popular and technical scientific literature, which he accessed not through formal training but in the diverse collections of Chicago’s public libraries — his substitute for a university experience.

In contrast to his experiences with science, Dubkin’s literary ambitions were much more fully realized and he carved out a singular niche as an urban naturalist-writer. His early dreams of becoming a naturalist and a writer were fulfilled most resoundingly by his string of urban nature writing books, published between 1944 and 1972, which creatively fused autobiography and natural history. These works included The Murmur of Wings (1944), Enchanted Streets (1947), The White Lady (1952), Wolf Point (1953), The Natural History of a Yard (1955), and My Secret Places (1972). Dubkin was a dedicated and prolific writer who kept a daily journal throughout his life; wrote hundreds of letters to family and friends, most notably to his wife, Muriel, who was both his muse and sounding-board; published hundreds of newspaper columns and scores of book reviews; and developed a variety of creative projects that never saw the light of day, including novels and a natural history from the viewpoint of the family dog amusingly entitled “Letters from Pepsi.”

In contrast to his experiences with science, Dubkin’s literary ambitions were much more fully realized and he carved out a singular niche as an urban naturalist-writer. His early dreams of becoming a naturalist and a writer were fulfilled most resoundingly by his string of urban nature writing books, published between 1944 and 1972, which creatively fused autobiography and natural history. These works included The Murmur of Wings (1944), Enchanted Streets (1947), The White Lady (1952), Wolf Point (1953), The Natural History of a Yard (1955), and My Secret Places (1972). Dubkin was a dedicated and prolific writer who kept a daily journal throughout his life; wrote hundreds of letters to family and friends, most notably to his wife, Muriel, who was both his muse and sounding-board; published hundreds of newspaper columns and scores of book reviews; and developed a variety of creative projects that never saw the light of day, including novels and a natural history from the viewpoint of the family dog amusingly entitled “Letters from Pepsi.”

As a journalist, Dubkin worked for several papers penning nature columns over the course of his life, including that youthful gig the Chicago Daily News and a brief stint at the Chicago Tribune that ended abruptly when he offended the Tribune’s publisher, Robert R. McCormick, by impugning the character and motives of life-list-constructing “bird lovers” — one of whom was McCormick’s wife. Later on, from the late 1950s until his death in 1972, he maintained a long-standing position at Lerner Newspapers in Chicago as a news reporter and nature writer; his popular “Birds and Bees” column containing his folksy yet scientifically informed observations on urban nature ran for nearly 30 years, and enjoyed a wide and dedicated readership throughout the city.

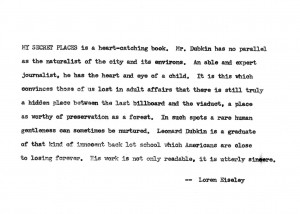

Once established as an accomplished naturalist-writer, Dubkin was in demand to pen reviews of books by his contemporary nature writers for such venues as the Chicago Tribune and the New York Times. He also maintained friendships and regular correspondence with important writers, naturalists, and scientists of his day, from legendary Chicago writer Nelson Algren to biologist and environmental writer Rachel Carson to anthropologist and essayist Loren Eiseley. In fact, it is Eiseley who penned what might be the most eloquent tribute to Dubkin’s skill and craftsmanship as a naturalist-writer. In a 1972 letter to Dubkin he included a carbon copy of a dust jacket blurb for Dubkin’s final book, My Secret Places:

Mr. Dubkin has no parallel as the naturalist of the city and its environs. An able and expert journalist, he has the heart and eye of a child. It is this which convinces those of us lost in adult affairs that there is still truly a hidden place between the last billboard and the viaduct, a place as worthy of preservation as a forest. In such spots a rare human gentleness can sometimes be nurtured. Leonard Dubkin is a graduate of that kind of innocent back lot school which Americans are close to losing forever. His work is not only readable, it is utterly sincere.[ii]

Eiseley concisely and poetically captures here several salient qualities of Dubkin’s perspective on nature and his literary voice. An esteemed member of the scientific establishment (an establishment that both inspired and intimidated Dubkin) and a writer who produced hard-to-categorize yet utterly compelling works that blended natural history, evolutionary theory, philosophy of science, and autobiography, Eiseley recognized not just the singularity of Dubkin’s unique perspective and literary ability but also the value of Dubkin’s lifelong efforts to bring the neglected yet fascinating manifestations of urban nature to light.

Notes

[i] The biographical information in this essay on Dubkin is culled from the author’s interviews with Dubkin’s daughter, Pauline Dubkin Yearwood, as well as from Yearwood’s short essay “Family Memoir: The Urban Nature Lover.”

[ii] This letter is part of the extensive manuscript collection of Dubkin’s writings and correspondence — including letters, journals, newspaper columns, book reviews, book manuscripts, fiction, poetry, and unpublished manuscripts — maintained by Pauline Dubkin Yearwood.

Works Cited

Dubkin, Leonard. Enchanted Streets: The Unlikely Adventures of an Urban Nature Lover. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1947.

—. The Murmur of Wings. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1944.

—. My Secret Places: One Man’s Love Affair with Nature in the City. New York: David McKay, Inc., 1972.

—. The Natural History of a Yard. Chicago: Henry Regnery Co., 1955.

—. Personal papers. Pauline Dubkin Yearwood, Chicago, IL.

—. The White Lady. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952.

—. Wolf Point: An Adventure in History. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1953.

Eiseley, Loren. Letter to Leonard Dubkin. 12 February 1972.

Yearwood, Pauline Dubkin. “Family Memoir: The Urban Nature Lover.” Chicago Jewish History (Fall 2005): 4-5.

—. Personal interview. 15 March and 18 April 2007.

* * *

This essay was written in August of 2008. It is an expanded version of the biographical information contained within my scholarly essay, “Empty Lots and Secret Places: Leonard Dubkin’s Exploration of Urban Nature in Chicago.” ISLE 18.1 (Winter 2011): 1-20.