This past Saturday, students in my SUST 220 Water and PLS 391 Natural Science seminars at Roosevelt University joined me for an urban ecology adventure on the Upper North Branch of the Chicago River. We convened mid-morning at Linné Woods, a woodland site locatedin the Cook County Forest Preserve system in Morton Grove, IL, where we met up again with Mark Hauser and Claire Snyder, naturalists from Friends of the Chicago River, for a water quality sampling session of the river where it flows past the lovely picnic grounds in Linné Woods.

While this was the second go-round for my 220 Water students on field sampling (our first session was further downstream on the North Branch, at West River Park in Chicago), the students from my natural science seminar were new to this exercise; however, after three weeks of being introduced to issues and concepts in urban ecology (from biodiversity to climate change), they were ready to get out in the field and get their hands dirty.

Breaking up into different teams, we measured key chemical indicators such as temperature, turbidity, pH, dissolved oxygen, nitrate, phosphate, and total dissolved solids; and wading into the river with D-nets to scrape up mud in search of macro-invertebrates (worms, leeches, crawfish, snails, damselfly nymphs, etc.), we also garnered a biological snapshot of the river’s relative quality.

Taken together, these two approaches give us an in-the-moment (chemical) and over-the-longer-term (biological) assessment of the ecological health of the North Branch. This is because while the chemical profile of a river can change day to day — even hour by hour — depending upon the weather and various inputs into the watercourse, the biological community in the river’s benthos is stationary; and some of organisms that live there have been there awhile.

Our quality results were decidedly mixed.The chemical profile we established had some indicators looking rather good, such as a low nitrate reading of 1.3ppm and a fairly neutral pH of 6.5; turbidity levels were also reasonable. The low nitrate reading makes sense, given that in this area of the northern suburbs north of Dempster Ave. (Glenview, Golf, Morton Grove), communities use a separate sewer system, so wastewater treatment plants are not burdened by high inputs of stormwater run-off, and the waterways do not received Combined Sewage Overflows as they do in older suburbs and the city. Moreover, there is not much, if any, agricultural land in this part of the river’s watershed, meaning that fertilizer run-off from farm fields is not an issue.

On the other hand, phosphate levels were rather high at 0.7ppm and the all-important indicator of dissolved oxygen was fairly low (at 7ppm and 60% saturation), posing challenges for many types of organisms to thrive in the river’s watercolumn and benthos. All in all, we calculated a “Quality Index” grade of 68% on our collective chemical analyses, or if you’re using a letter-grade system, D-plus. Nothing to write home about, despite the lovely, even bucolic, scenery in this part of the Chicago River which follows its natural watercourse and winds through forest preserve land. This assessment was echoed rather closely by our macro-invertebrate survey, which identified 8 different taxa of organisms, ranging from several that are “modertely intolerant to pollution” to four that are “fairly” to “very tolerant” of impaired water quality. Our Water Quality index of 2.6 was on the low end of “fair” in terms of biological diversity (call it a C-minus).

Finally, our group waded into the stream and use measuring tape, rules, a stopwatch, and a collection of sticks to calculate the stream flow rate. The trick here is to stake out a place where the width and depth of the river is known, and then release the sticks in the current. Students time how long it takes each stick to travel a given distance (here, 40 feet) and then calculate the stream flow (cubic feet/second) accordingly. Our result: a stream flow rate of 98 cubic feet per second.

Curious readers can review our original field data sheets and calculations here; and for photos of our water sampling activities, see this online slideshow.

- Linne Woods water chemistry data 2012-10-20 (pdf)

- Linne Woods macro-invertebrate data 2012-10-20 (pdf)

- Linne Woods streamflow data 2012-10-20 (pdf)

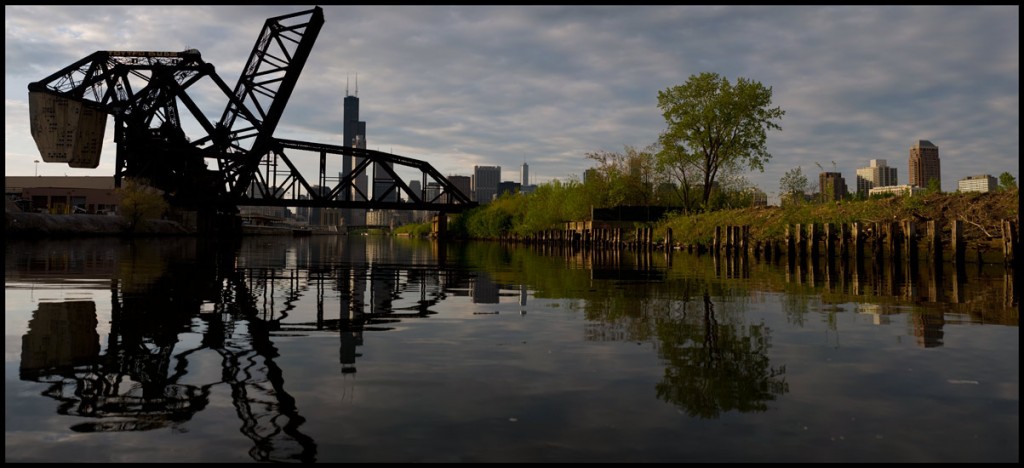

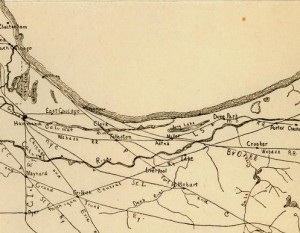

After a picnic lunch, we used several of our vehicles to shuttle our group up to our canoe launching spot five river miles north, at Blue Star Memorial Woods in Glenview. Here we met up with Dave Rigg and his fellow volunteer canoe guides from Friends of the Chicago River, who would lead us on an intimate exploration of the water, woodlands, and wetlands of the West Fork of the Upper North Branch of the Chicago River — one of the most scenic and naturalistic stretches of the entire Chicago River system. Dave and Co. gave the many inexperienced but enthusiastic paddlers in our group a paddling lesson, and once outfitted with our safety gear, paddles, and a canoe partner, we hit the water for what would be a two-hour downriver journey in utterly perfect October weather.

The majority of this trip runs through forest preserve property, with the notable exception of the Chick Evans Golf Course that straddles the river where the North Branch splits into its Middle and West Forks. The result is that we traveled along the natural course of the stream, mostly unchanged from before the time of European settlement, with all its twists and turns and with a wide buffer zone of floodplain forest. The heavily vegetated riverbanks proved to be a stunning contrast to the reinforced concrete and rusty steel that encases much of the Chicago River further south in the watershed.

Besides navigating all the twists and turns of a sometimes narrow and always lovely river channel, as well as ducking under overhanging branches, we had to negotiate two portages — the first for a couple of large downed trees, the second for a dam that is slated by the Cook County Forest Preserve for future removal, since it no longer serves a practical purpose and has deleterious impacts upon the river’s flow, water quality, and recreational value.

These proved to be an interesting and fun challenge, though — especially given our previous contemplation of the long portages done by explorers and Native Americans between the West Fork of the South Branch, through the wetlands of Mud Lake, to the Des Plaines River (a place now commemorated by the Chicago Portage Historic Site).

More photos of our canoe trip can be seen in this online slideshow. In the near future, I’ll post some additional comments about the state of the river and its surrounding landscape that we observed on this trip.