If you had met Millie Bryson for the first time in the last few months of her life, it would have been easy to underestimate her. She was 98 years old, blind, hard of hearing, and increasingly forgetful. She lived in a humble and charmingly disordered house that hasn’t changed much over the last few decades. She moved around gingerly, by feeling her way along furniture and walls, and she slept a lot. One of the surest signs to me that she was finally slowing down in her late 90s was that she stopped following every inning of every game of her beloved Chicago Cubs.

But such observations would belie my Grandma Millie’s many accomplishments and talents, as well as the humor, passion, knowledge, and wisdom she shared over the course of her long and influential life.

First and foremost, Millie Bryson was a true force of nature possessed of both tremendous energy and a winning personality. Fiercely independent and strong-willed, she had a quick wit and delightful laugh — qualities she retained even after going blind late in life. And she was smart. A sharp thinker, an avid reader, a skilled crossword puzzle-solver, she had brains to go along with her impressive command of the English language.

Speaking of English, Gram was a stupendously energetic talker. She perfectly embodied the phrase “having the gift of gab.” In her prime, which lasted from the moment she started talking to well into her 90s, Gram could pretty much dominate any conversation she happened across. Once she became partly deaf in her later years, she could turn her hearing aids down low and happily keep on going and going without ever being troubled by an audible interruption.

I’ll never forget one summer when she was in her 80s and my wife and I drove her up north to Michigan for one of her final visits to the Bryson summer home. For about nine straight hours, she talked non-stop, including through the two meals we took along the way. I don’t think Laura and I spoke more than ten words the entire trip. After we arrived and the evening wore on, she began a violent and loudly percussive series of coughs and throat clearings that went on well into the middle of the night. “I don’t understand why my throat is so sore,” she said, much to our amusement. “I must have caught a little bug or something.”

Gram’s passion for conversation bespeaks her role as the oral historian of the family. She was the repository of family lore, and with her amazing memory could recite dialogue from a 1930s afternoon gathering word-by-word at the drop of a hat. Besides her vast knowledge of Bryson and Hicks genealogy, she possessed a seemingly limitless supply of fascinating family stories, as well as an arsenal of memorable sayings that usually surfaced spontaneously within the appropriate social context. A few chestnuts from these aphorisms include:

“First the worst, second the same, last the best of all the game.”

“Wish in one hand and spit in the other, and see which one gets filled up faster.”

“Why? You want to know why? Because the boat leaves Friday, that’s why.”

“What for, you ask? For cat’s fur, to make you kitten britches.”

Millie also was a terrific musician who was born into a musical family — her father, Leslie Hicks, played banjo and guitar in Charlie Formento’s Dance Band during the Depression years here in Joliet. Gram became an accomplished pianist who could sight-read expertly. She had a lovely alto voice and was equally at home singing in the church choir or directing it. She instilled a profound and lasting love of music within her family, and was a nifty dancer to boot.

Faith and church involvement were foundational to Gram’s life. Long a member of First Baptist Church on Joliet’s East Side, she was a founder and charter member of Judson Memorial Baptist Church on the West Side in 1955. For decades she was a respected leader in church affairs at Judson, particularly music, education, governance, and mission outreach. Millie played organ and piano, directed the choir, served as deaconess, taught Sunday School, raised money for mission work, led women’s Bible studies, and performed countless other services for the church community. She lived her faith through deeds more than words, and many of us benefitted from her example.

Gram was an amazing cook who was generous with her skills, knowledge, and recipes for those eager to learn (including my mother). Family dinners at her home on Oneida Street were legendary. She routinely prepared elaborate meals singlehandedly in her miniscule kitchen, and she was a skilled confectioner of pies, cakes, rolls, donuts, cookies, and a special chocolate sauce.

Besides her cooking, she was an expert seamstress. For many years she made her kids’ outfits as well as most of her own clothes. I have it on good authority that her embroidery work was nothing short of exquisite.

More significant than these many talents is that she stepped up when she was needed. As the Bryson matriarch and a beloved mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother, Millie was utterly devoted to her family. For over two decades she took care of elderly relatives in her small home even as she raised her own children. Most people would find this difficult to do for 24 days, if not 24 hours — she did it for 24 years.

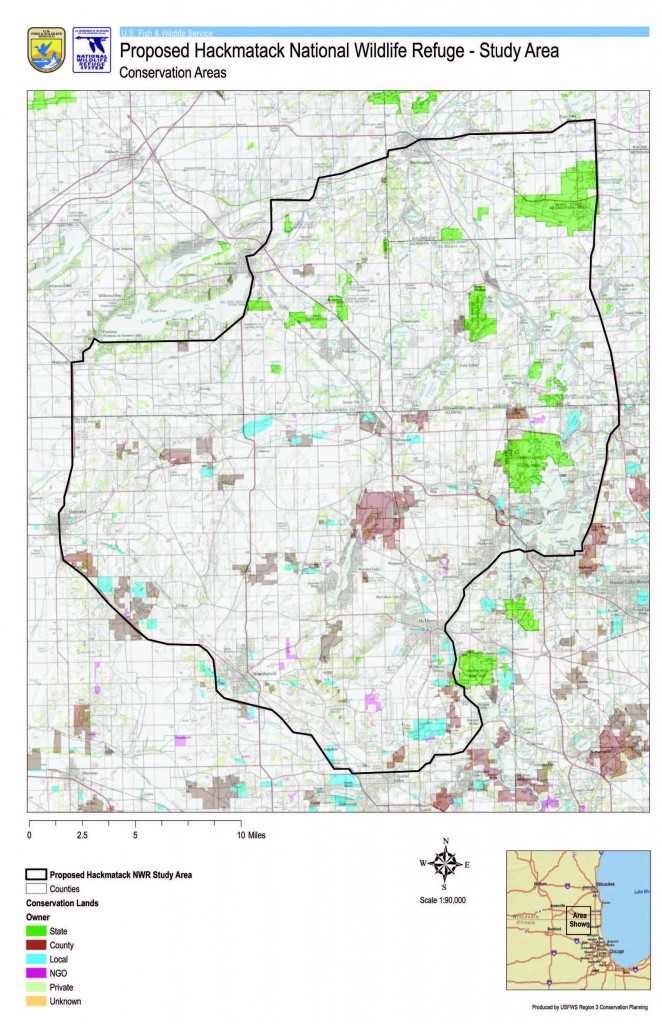

As that previous example shows, Millie often sacrificed her own comforts and conveniences for the sake of others. She could see the bigger picture and act accordingly. Consider that tiny kitchen I mentioned before. Back in 1960, she and my Grandpa Abe decided to use the money they had long saved for a kitchen expansion/remodel to instead purchase a small rustic cabin in the north woods of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. No-one could deny that a talented and hard-working cook like Millie surely deserved a bigger and better theater for her daily labors. But to my knowledge, she never regretted that decision for a second.

Ever since, the Bryson cabin at Crooked Lake has been a treasured vacation site for four generations of the Bryson and Laury families. And though she was city bred and couldn’t swim a stroke, Gram came to enjoy camping out, and learned how to handle a canoe in rough water and pitch a tent in the rain.

Speaking of dealing with adversity, Gram knew the meaning of devotion, heartbreak, and deferred gratification. By this I mean she was a Cub fan. I’m talking Hack-Wilson-is-your-favorite-Cub-of-all-time type of Cub fan. Gram dated her devotion to baseball to the summer of 1929, when she began hanging out with the menfolk at picnics listening to ballgames on the radio. It wasn’t very lady-like behavior according to some tongue-waggers, but Millie didn’t truck with convention if it didn’t suit her. She followed her beloved Chicago Cubs on the radio “through thin and thin,” as she often noted wryly — year after disappointing year, decade after excruciating decade, century after spirit-crushing century.

She borrowed this memorable phrase “though thin and thin” many years ago from her soon-to-be son in law of 50+ years — Everett Laury of Danville, Illinois — who uttered it upon meeting Millie at her house for the first time. From that point on, once she knew Ev was a fellow Cub fan, he was A-OK in her book. Another special moment in her baseball life was when Cubs radio announcers Pat Hughes and Ron Santo paid a lengthy tribute to her on the air during her 90th birthday. I’ll never forget the look on her face as she listened to their humorous patter, and then said, “Gee, that was dandy!”

Many times over the past few years, when I would bring my two daughters over to her house for a visit, Gram would say to me, “Oh, I don’t know why I keep hanging around so long. I’m just a burden to people. What do I have to live for at this point? Why am I still here?”

For me, the answers to her rhetorical questions came easy. To hear the Cubs play another game, and maybe, just maybe, win the pennant at long last. To share love. To teach us. To bring joy. To appreciate an earthly life well lived, and anticipate the eternal life to come.

Speech delivered at the memorial service for Millie Bryson (1914-2012) held at Judson Memorial Baptist Church, Joliet, IL. (pdf version)