For the last several months, the Great Lakes Commission and the US Army Corps of Engineers have been conducting parallel studies on the feasibility of re-separating the Great Lakes and Mississippi River watersheds here in the Chicago Region. This challenging process is motivated by the threat of Asian Carp moving northward from the Illinois Waterway system through the Chicago and/or Calumet Rivers and into the Great Lakes.

While the Corps’ study is wide-ranging and focused on the Asian Carp threat throughout the Mississippi River and Great Lakes basins — and thus on a much slower timetable, to the frustration of many environmentalists and regional governmental leaders — the Great Lakes Commission has just released its full report, “Restoring the Natural Divide,” to the public. As noted here by the Chicago Tribune’s Andrew Stern and Sandra Maler,

Keeping the invasive Asian carp out of the Great Lakes will involve re-reversing the flow of the Chicago River — an engineering marvel completed a century ago through a complex network of rivers, canals, and locks, a new study said on Tuesday.

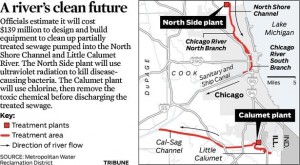

The study proposed three options to separate the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River basin near Chicago and keep Asian carp and other invaders out but all three would require re-reversing the flow of Chicago river which now carries Chicago’s treated waste water away from its Lake Michigan drinking water.

“Physically separating the Great Lakes and Mississippi River watersheds is the best long-term solution for preventing the movement of Asian carp and other aquatic invasive species, and our report demonstrates that it can be done,” said Tim Eder, executive director of the Great Lakes Commission, sponsor of the study with several other interest groups.

The prolific Asian carp have populated the Mississippi River and many of its tributaries and now threaten the $7 billion fishery in the lakes, which contain one-fifth of the world’s fresh surface water and supply 35 million people with drinking water.

The invasions by Silver and Bighead carp, first introduced to control algae in commercial fish ponds, have prompted promotional efforts to catch them as a source of cheap protein or for sport fishing, but their populations have exploded.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is conducting its own long-term study on possible separation of the watersheds that is due to be completed in 2015, has erected electric underwater barriers at a canal bottleneck near Chicago to try to keep the carp at bay, but some marine experts fear the carp may have already bypassed the barriers.

Several states bordering the lakes have demanded stronger action and have filed a suit against the Army Corps calling for quick action to erect separation barriers and speed up its study.

Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette, who is pursuing the states’ lawsuit, praised the Commission’s study, saying “with thousands of jobs and a spectacular ecological resource at stake, we can no longer afford to wait for the federal government.”

Commercial shippers and the recreational and tour boat industries have opposed closing locks and dams between the two watersheds, saying it would destroy their businesses. Previous federal court rulings have also noted closing locks permanently would worsen flooding during storms.

Four Indiana congressmen issued statements objecting to the economic cost to the northwest corner of the state if plans are undertaken to permanently divide the two watersheds. . . .

Environmental groups backed the separation plans, with Marc Smith of the National Wildlife Federation saying the study “puts solutions on the table that are both feasible and affordable.”

The Commission’s 18-month-long study estimated the total cost of erecting barriers to achieve ecological separation and measures to address water quality, flood prevention and alternative transportation at up to $9.5 billion.

The least costly option, the “Mid System” approach, would cost between $3.3 billion and $4.3 billion and involve erecting four barriers including one near the existing O’Brien Lock nearly Lake Calumet. At that point, a facility could be built to transfer cargo between river barges and trains, trucks, or lake-going boats. A second barrier on the Chicago River could be equipped with a system to lift and transfer recreational boats from one side to the other.

Another option would place five barriers in waterways closer to Lake Michigan, and a third would place one barrier further downstream. Both pose significant transportation and flood management challenges, raising the costs to more than $9.5 billion, the study said.

The study projected a two-phase implementation of the plans with an initial target to erect barriers by 2022. Flood protection depends in part on completion by 2029 of a $3.7 billion system of tunnels and reservoirs designed to divert Chicago area’s stormwater, a project begun in the early 1970s.

Besides Asian carp and its ability to scour the lakes’ food supply and out-compete other fish species, the Army Corps has identified 39 other invasive species — 10 poised to enter the lakes and 29 ready to invade the rivers — that could traverse the two watersheds and threaten the ecological balance. Those include fish such as the northern snakehead, plants such as the water chestnut and mat-forming hydrilla, and crustaceans such as the spiny water flea.

A total of 180 non-native aquatic species are established in the Great Lakes, and 163 are established in the Mississippi River basin.

What will be interesting to see is how the Great Lakes Commission’s report impacts the current dialogue about the best way to proceed in keeping the Asian Carp at bay while simultaneously assuring the economic and environmental sustainability of the Great Lakes-to-the-Gulf of Mexico shipping connection. In the meantime, I recommend the Report’s extensive website, which also features abundant video and image resources.

Sandra receives some worrying results and is thrust into a period of medical uncertainty. Thus, we begin two journeys with Sandra: her private struggles with cancer and her public quest to bring attention to the urgent human rights issue of cancer prevention.

Sandra receives some worrying results and is thrust into a period of medical uncertainty. Thus, we begin two journeys with Sandra: her private struggles with cancer and her public quest to bring attention to the urgent human rights issue of cancer prevention.