This April is #RUEarthMonth2019, and there are lots of ways to go green at Roosevelt as part of our campus sustainability efforts — from recycling and composting promotional events to fun urban ag field trips to our annual sustainability symposium. We’ll add to and update this list as the month unfolds, so please check back frequently!

All Month — Participate in RU’s waste reduction efforts every day by using and promoting our new compost bins, which are now located literally everywhere. help us divert waste from the landfill and reduce our GHG emissions by rinsing out your recyclables and putting biodegradable waste in the compost. It’s easy and fun!

All Month — Environmental Justice and Policy online activism: Students, please take this 1-minute survey developed by the SUST 250 Sustainable University water team about bottled water usage here on campus. All, please read this environmental justice petition from our friends at the Southeast Environmental Task Force, where recent RU alum Yessenia Balcazar (BA ’18, Sustainability Studies) works as an EJ advocate; please sign and share as your conscience dictates.

Fri 4/19 & 4/26 — Field Trip to Washington Park Youth Farm with Windy City Harvest: Join SUST Prof Vicki Gerberich and students in her SUST 230 Food class on this urban ag field trip. Open to students, faculty, staff, & alumni. Small fee, big-time fun. Details here!

Mon 4/22 — Earth Day is here! Get outside if you can, rain or shine. Then, when you come back inside, join students from the SUST 250 Sustainable University class and RU Green as they promote our new composting initiative in that nexus of RU food consumption, the RU Dining Center, from 12-5pm. There may be prizes (or at least a pleasant endorphine rush) for tossing your stuff in the right bin. Plus, you can avoid otherwise unpleasant tasks by taking an Earth Day Quiz and reading these Earth Day Tips!

Tues 4/23 — RU Green Nature Outing: Join students from the environmental org RU Green on an urban nature adventure to McKinley Park, where they’ll help out the park by picking up litter and planting seeds, then have a nice little picnic. Meet at the SUST Lab, AUD 526, at 5pm; RSVP to RU Green president Samantha Schultz (sschultz10@roosevelt.edu).

Wed 4/24 — WB Rooftop Garden Work Day: Fresh air and fun! Get your hands dirty with those tireless and enthusiastic students from RU Green as they work on our 5th story Rooftop Garden from 5-6pm. Space is limited, so RSVP to RU Green president Samantha Schultz (sschultz10@roosevelt.edu) to save your spot. Bring extra oxygen for working at high altitude. (Just kidding. Work gloves would be good, though, if you’ve got ’em.)

Thurs 4/25 — Meet Recycling & Composting Expert Rebecca Quesnell: One of the living legends among the many SUST alumni working for positive change out there in this great big world of ours is Rebecca “Beeka” Quesnell (BA ’15 Sustainability Studies), who now works as the Sustainability Coordinator for Independent Recycling Services. That’s huge, because Independent collects RU’s recyclables at the Chicago Campus! Stop by the info table in the WB Lobby from 11:30am-2pm to chat with Beeka and current SUST students, get your burning questions about recycling/composting answered, and feel enlightened.

Thurs 4/25 — Meet Recycling & Composting Expert Rebecca Quesnell: One of the living legends among the many SUST alumni working for positive change out there in this great big world of ours is Rebecca “Beeka” Quesnell (BA ’15 Sustainability Studies), who now works as the Sustainability Coordinator for Independent Recycling Services. That’s huge, because Independent collects RU’s recyclables at the Chicago Campus! Stop by the info table in the WB Lobby from 11:30am-2pm to chat with Beeka and current SUST students, get your burning questions about recycling/composting answered, and feel enlightened.

Thurs 4/25 — RU Green Farmers Market Outing: Join those always-adventure-seeking students from RU Green on a jaunt to one of Chicago’s many urban farms and markets, Growing Home, at their Wood Street Urban Farm Stand. Meet at the SUST Lab, AUD 526, at 12:45pm; RSVP to RU Green president Samantha Schultz (sschultz10@roosevelt.edu) to let her know you’re coming.

Fri 4/26 — Field Trip to Growing Home Farm at 1pm. Because you really can’t go to Growing Home enough, can you? Yet another outstanding field trip opportunity with SUST Prof Vicki Gerberich and students in her SUST 230 Food class. Growing Home has been using urban agriculture as a catalyst for change for over a decade in Englewood, an underserved community on Chicago’s South Side. Open to students, faculty, staff, & alumni. Details and RSVP here!

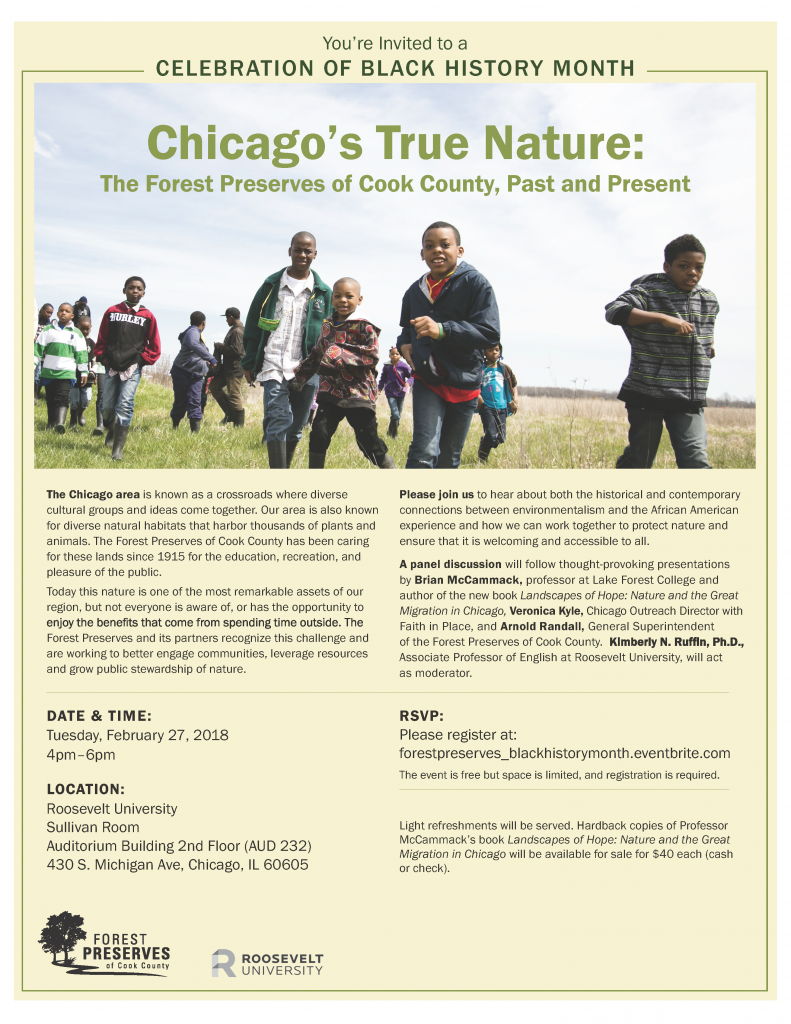

Sat 4/20 & Sat/Sun 4/27-28 — Earth Day Service Opportunities & Events throughout Chicago, sponsored by the Chicago Conservation Corps (C3) and other organizations. Check out the many events listed here by C3 as well as these by the Cook County Forest Preserves. Help clean up parklands, restore natural areas, and meet conservation-minded and nature loving sustainability nerds from across the city. Fun and rewarding in a deeply spiritual and dirt-under-your-nails kind of way!

Wed 5/1 — SUST Student Symposium: An annual festival of student creativity and action research that features four team presentations by RU undergraduate students in Prof. Mike Bryson’s SUST 250 The Sustainable University class. Food. From 2-4pm in WB 1214, teams will describe their work on campus sustainability projects on food waste reduction in the Dining Center, recycling/composting in the WB Dormitory, rooftop gardening, solar energy generation, and water conservation. Free food. From 4-5pm we’ll feature two individual presentations: SUST senior Bria Jerome will recount her adventures this spring as RU’s first-ever intern at Seven Generations Ahead in Oak Park and Chicago; and distinguished SUST alum Yessenia Balcazar (BA ’18) will talk about her path from RU to working with the Southeast Environmental Task Force on the front lines of the environmental justice on Chicago’s Far South Side. Did I mention food above? [Quite possibly.] Yes, refreshments will be served! RSVP to Prof. Mike Bryson (mbryson@roosevelt.edu) to feed your brain AND your belly.

Wed 5/8 — Bubbly Creek Clean-up: Join students in Prof. Mike Bryson’s SUST 250 Sustainable University class on the field trip to Canal Origins Park on Chicago’s Near Southwest Side, where we’ll continue our yearly tradition of picking up litter along the riverbanks of Bubbly Creek where it meets the South Branch of the Chicago River. Enjoy great views of the Chicago skyline, fresh air, and a gratifying sense of fun and companionship as we work together to clean up our adopted city park! Meet at 2pm in the WB Lobby; RSVP to Prof. Mike Bryson (mbryson@roosevelt.edu) with questions and to confirm attendance.

This event list will be updated throughout Earth Month and maybe a little bit beyond.