pdf version

pdf version

Category: Science

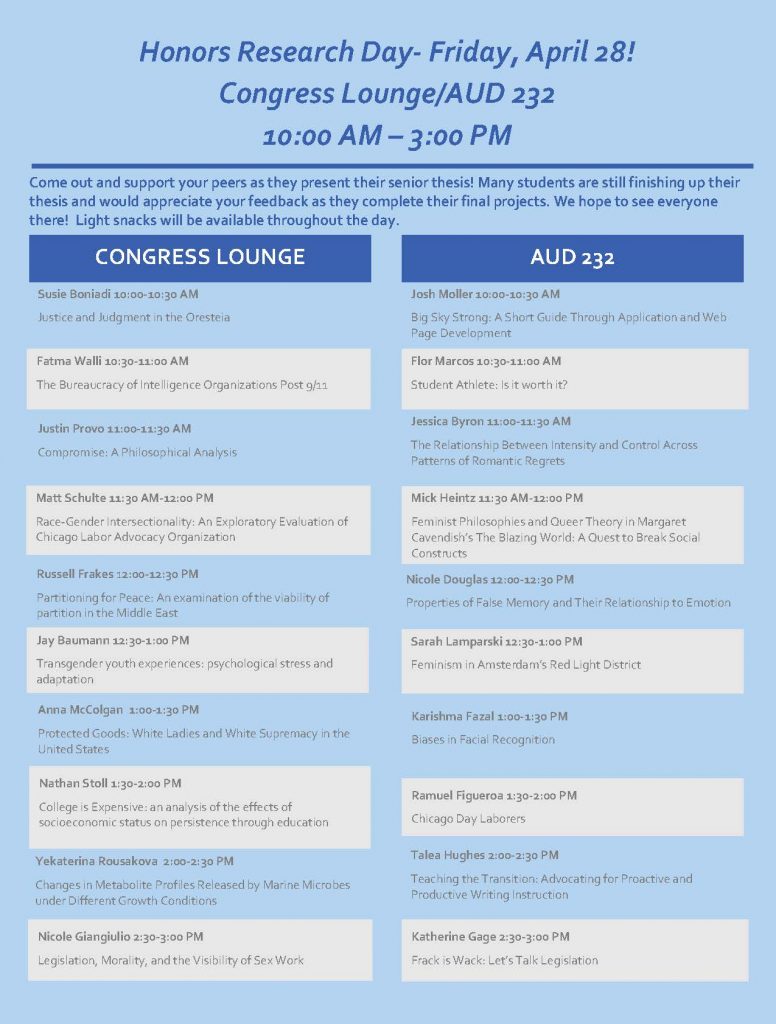

Today is Honors Research Day @RooseveltU’s Chicago Campus

Also see the pdf version of this image.

Also see the pdf version of this image.

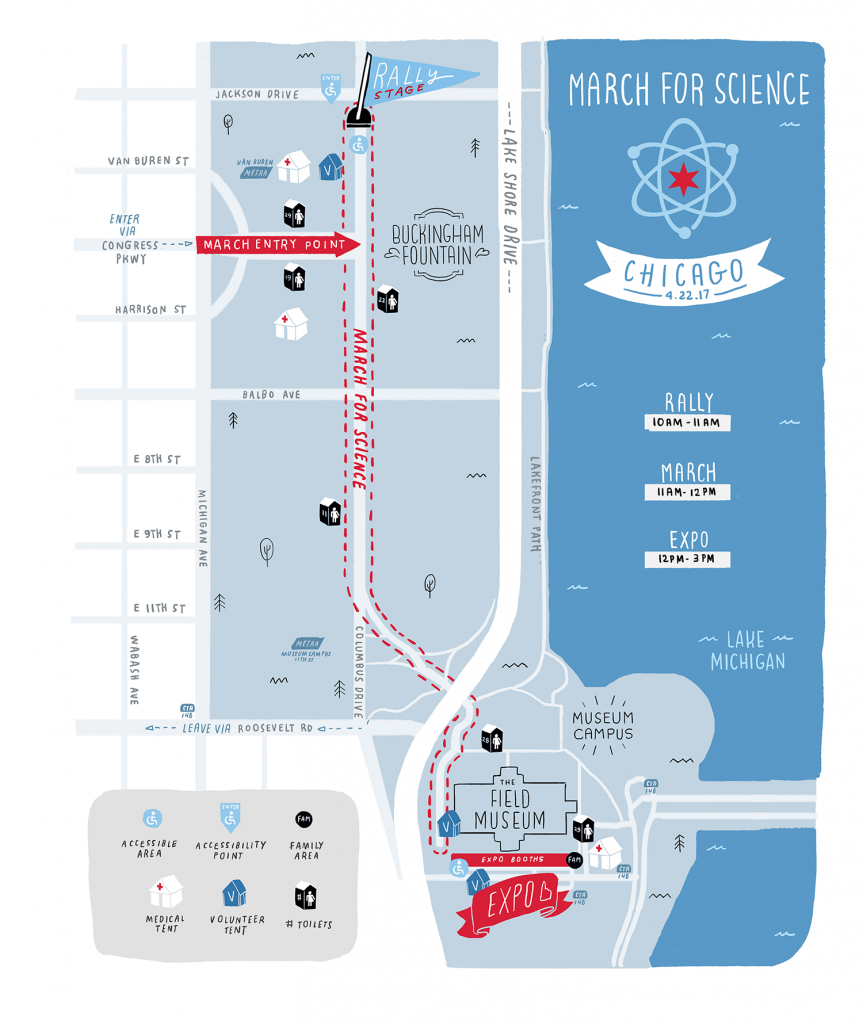

Earth Day 2017: Mapping the March for Science in Chicago! #MFSChi @sciencemarchchi

March for Science in Chicago on Earth Day 4/22

Join faculty and students from Roosevelt’s SUST program and the Department of Biology, Chemistry, and Physical Science as we in the RU community march for science! We’ll meet in the WB Lobby at 9:00am, after which we’ll walk over to Grant Park in time for the 10am rally that kicks off the day’s events. After a round of speakers, participants will march at 11am from Grant Park to the Museum Campus for a cool science expo planned for 12-3pm outside the Field Museum. Official visitor and registration details here.

Join faculty and students from Roosevelt’s SUST program and the Department of Biology, Chemistry, and Physical Science as we in the RU community march for science! We’ll meet in the WB Lobby at 9:00am, after which we’ll walk over to Grant Park in time for the 10am rally that kicks off the day’s events. After a round of speakers, participants will march at 11am from Grant Park to the Museum Campus for a cool science expo planned for 12-3pm outside the Field Museum. Official visitor and registration details here.

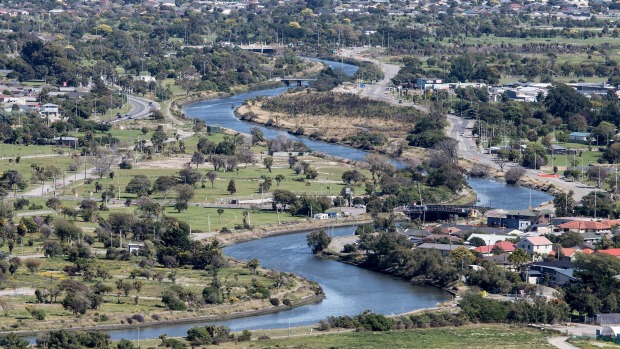

Water Stories: Narrative, Urban Sustainability, and the Fluid Future of the Otakaro-Avon River in Christchurch, New Zealand

Twenty-five years ago, I had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to travel to Antarctica as part of a scientific research expedition from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Taking a semester’s leave from my graduate studies at SUNY Stony Brook, I worked for two months as a field technician and writer-in-residence on a team researching the biogeochemistry of Lake Fryxell, a permanently frozen-over lake in Antarctica’s Dry Valleys. This extraordinary experience was memorable in many ways, including a brief three-day stopover in New Zealand, where we made our final preparations at the US Antarctic Program’s headquarters in Christchurch before flying to McMurdo Station on the Ross Ice Shelf.

Now as a mid-career academic seeking new challenges and opportunities beyond my Midwestern home at the southern rim of the Great Lakes — and having traveled outside the US (to Canada) only twice during this time — I decided to apply for a Fulbright Scholar fellowship to explore a distant locale that has always resonated powerfully in my memory. But this time, instead of a mere fleeting taste of Christchurch and a brief fly-over of the North and South Islands, I hope to spend several months in 2018 researching, writing, and living in New Zealand, based at Lincoln University a few kilometers outside of Christchurch, in order to enrich my understanding of urban river ecosystems as well as gain a much-needed global perspective on my scholarship and teaching.

Now as a mid-career academic seeking new challenges and opportunities beyond my Midwestern home at the southern rim of the Great Lakes — and having traveled outside the US (to Canada) only twice during this time — I decided to apply for a Fulbright Scholar fellowship to explore a distant locale that has always resonated powerfully in my memory. But this time, instead of a mere fleeting taste of Christchurch and a brief fly-over of the North and South Islands, I hope to spend several months in 2018 researching, writing, and living in New Zealand, based at Lincoln University a few kilometers outside of Christchurch, in order to enrich my understanding of urban river ecosystems as well as gain a much-needed global perspective on my scholarship and teaching.

Objectives and Methodology: My proposed project focuses on the Otakaro-Avon River that flows through Christchurch, NZ, as a natural and human ecosystem undergoing stress and change. The Otakaro-Avon is an important focal point of urban sustainability planning and ecological restoration. Using the qualitative research framework of the environmental humanities, which blends insights and analytic methods from literary studies, environmental history, ecology, and other disciplines, I plan to undertake an ecocritical study of this urban river’s history, present condition, and future prospects in the context of urban redevelopment underway after the 2011 earthquake that devastated Christchurch and many of its suburbs. This place- and observation-based perspective on the Otakaro-Avon watershed merges humanistic scholarship with physical exploration of the river as a highly modified, impaired, yet still biologically rich ecosystem with great sociocultural significance.

I will examine a wide range of “water stories” focused on the river — from historical documents to scientific analyses to technical reports — as well as current representations of the river in post-earthquake planning documents and journalistic accounts; conservationist, community-based, and indigenous discourse; plans for memorials and sustainable redevelopment along the river; and works of literature, film, and online media. This research will influence the crafting of my own stories of the Otakaro-Avon River and its fluid future, based on my in-the-field observations and experiences, in both narrative forms suitable for general readers as well as in scholarly prose for academic audiences — much as I have done in my recent work on the Chicago River‘s history, ecology, and future sustainability.

Key questions to be addressed in this project include but are not limited to:

- How has the Otakaro-Avon River been utilized, modified, polluted, exploited, abused, defended, etc. over time? How does the history, quality, and character of the river inform people’s relationship to its present state and future prospects?

- In what ways is the river important, economically and culturally, to the Maori indigenous people (as mahinga kai, a food-gathering place) as well as New Zealanders of European descent? How do people in Otakaro-Avon River’s watershed connect to the waterway? What kinds of activities do they undertake in terms of recreation, industry, and conservation?

- What role do the river’s conservation and restoration have in the ongoing redevelopment of Christchurch’s Red Zone and within the city’s future sustainability?

- How do the above issues intersect with questions of environmental justice, especially with respect to toxic pollution, public access to water resources and open space, and iwi (indigenous people) living with the Otakaro-Avon River watershed?

As an interdisciplinary-minded scholar within the environmental humanities, I employ a qualitative research approach. Using the analytic tools of ecocriticism, I emphasize the close reading and analysis of individual texts, their relationships with one another, and their place in the broad contexts of scientific discourse, nature writing, environmental history, and sustainability. At root, my work starts from the premises that the urban environment (both built and natural) is a worthy object of study; that natural resources are imperiled and therefore in need of protection and conservation; and that humanistic inquiry about the myriad relationships between humanity and nature in cities can foster, in the long run, ecological awareness and environmental progress.

Academic and Professional Context: Urban rivers are many things simultaneously: corridors of biodiversity, green infrastructure for storm water retention, transportation arteries for commerce, waste sinks, places of human recreation, and sites of environmental restoration. This partial list illustrates their dual nature: waterways in cities are all too often heavily polluted, modified, and abused ecosystems that bear scant resemblance to their former selves. They function as receptacles of waste and servants of commerce/industry, at the expense of water quality and biodiversity; and in many cases, city dwellers are physically as well as culturally cut off from access to waterways.

Yet urban rivers also harbor tremendous renrenga ropi (biodiversity) and exhibit a capacity to connect citizens to the natural world that exists cheek-by-jowl with the built environment as well as to their cities’ natural and cultural histories. In this sense, damaged urban water systems are pathways of connection that can foster a sense of place vital to building an environmental ethic of care among city dwellers.

Geographers, urban ecologists, environmental scientists, and sustainability scholars are assessing waterways as a critical component of urban ecosystems. Given that cities consume energy and resources from far beyond their geographic boundaries and produce high levels of waste as well as greenhouse gases, their future sustainability depends upon large-scale actions such as repairing water/wastewater infrastructure, conserving energy, improving transportation access and efficiency, enhancing biodiversity, and reducing material waste.

Such goals are complicated and made urgent by the destructiveness of natural disasters. The 2011 Christchurch earthquake provides a monumental challenge as well as golden opportunity for inclusive and socially just urban planning that embraces environmental sustainability as a central goal. Unsurprisingly, the Otakaro-Avon River is prominent within this planning and rebuilding process (and illustrative of its many challenges).

More broadly, urban rivers provide a specific context for assessing the impacts of global urbanization on human relationships to nature. As of 2015, over 50% of the world’s population is urban; in the US and NZ, that figure is 82% and 86%, respectively, according to the World Bank. A consequence of this is a pervasive (though hardly universal) alienation from the natural world of urban citizens. River systems constitute important natural resources where people can have direct and meaningful contact with nature close to where they live.

The stories we tell about cities and rivers are a means of grappling with the ideas and questions noted above. While the natural and social sciences generate vital empirical data on urban rivers, the role of the arts and humanities is uniquely critical to understanding urban waterways and our relationships to them. Our “water stories” are both a means of representing our values and history as well as a method of critique. The fundamental power of storytelling within human experience points to the impact of artistic expression and humanistic analysis on understanding the importance of waterways within urban ecosystems and human communities.

Significance of Study: Understanding the role of water in urban ecosystems is vital to improving the resilience of cities (e.g., protecting people and property from floods and other environmental disasters) and making them more sustainable (e.g., improving water retention and quality through expansion of green infrastructure). Cities are where most people in the world now live, a trend that will continue in coming decades as we grapple with the impacts of climate change, water quality degradation, toxic pollution, and environmental injustice. As a vital resource for all human communities, water is an important node of inquiry within environmental science and, more broadly, sustainability studies.

Urban rivers (and their watersheds, which include tributaries, wetlands, and estuaries) are ideal barometers of the ecological and socio-cultural health of our cities as well as our attitudes about and connections to the natural world. The Otakaro-Avon River is one of New Zealand’s most polluted waterways and, at the same time, one of its most important — both ecologically and symbolically — given the high number of people who live and work within its watershed and its centrality within the city’s earthquake recovery process.

Enhancing our knowledge, awareness, and appreciation of the river’s status and value is vital to its remediation and restoration as a living ecosystem that is not just an integral part of Christchurch’s green infrastructure, but also a significant thread within the city’s historical and cultural fabric. My research will explore how stories have defined the Otakaro-Avon River thus far, and how new ones might shape its sustainable future.

Why New Zealand? As an island country distinguished by highly diverse ecosystems, small and large cities, a vibrant indigenous culture, famously productive agricultural lands, longstanding conservation values, and threatened ecosystems and natural resources, New Zealand is a remarkable laboratory for exploring questions of environmental sustainability in the early 21st century.

Possessing a uniquely complex postcolonial mix of people from indigenous Maori (tangata whenua), European, and trans-Pacific Island cultures, New Zealand is progressive in its formal and structural recognition of indigenous rights, which has important implications for urban sustainable development and environmental conservation. More locally, Christchurch is a vitally important urban center: not only is it the biggest city on the South Island (pop. ~366,000), but its ongoing efforts to recover from the devastating earthquake in 2011 make it a test case for how cities can respond to natural disasters and seize opportunities to improve the sustainability of urban infrastructure, revitalize waterways, increase open space, enhance biodiversity, and involve the citizenry within the ongoing planning and reconstruction process.

Lincoln University: An incredible wealth of people and resources exist in and around Christchurch that would be invaluable to me as a scholar and writer. The Faculty of Environment, Society, and Design and its Department of Environmental Management at Lincoln University — a land-based institution located near Christchurch with a phenomenal array of environmental academic programs and research centres — offer an interdisciplinary community of scholars and teachers dedicated to environmental research and sustainability education.

LU’s Centre of Land, Environment, and People (LEaP), which is closely affiliated with the aforementioned Faculty, provides an intellectual home for research and collaboration with scholars and students from diverse disciplines spanning the natural/social sciences, the humanities, and various technical fields. Additionally, the Waterways Centre for Freshwater Management, a research collaboration between LU and the University of Canterbury, has published a wealth of technical reports on water resources throughout the Christchurch metro area and the Canterbury region, and would be an invaluable resource for advice and collaboration.

SUST Symposium 3.1 (Spring 2016) Today at RU

Today, April 27th, is officially my favorite day of the semester: Symposium Day! Please join me at today’s Sustainability Studies Program at Roosevelt University for a special afternoon Symposium of student projects and research from 2:30-5:30pm in RU’s LEED Gold-certified Wabash Building at 425 S. Wabash Ave. in downtown Chicago (room 1214).

Students in Roosevelt’s SUST program will give presentations about their recent campus sustainability projects, internships, and research experiences in a forum that is open to all RU students, faculty, and staff as well as the general public. The Symposium also will be videoconferenced via Zoom, so you may attend online or by phone, if you wish (see below).

I’m exceedingly proud of all of these students and the work they’ve done this semester. Break a leg, everyone!

Featured Student Speakers

Members of SUST 390 Sustainable Campus (honors) — From Plan to Action: Moving Sustainability Forward at RU

Members of SUST 390 Sustainable Campus (honors) — From Plan to Action: Moving Sustainability Forward at RU

Students in the Spring 2016 honors seminar “Sustainable Campus” will start our Symposium with a series of group presentations on their campus sustainability projects undertaken this spring to help advance RU’s Strategic Sustainability Plan across several fronts. Teams will discuss their initiatives in four areas: general education curriculum (Nicole Kasper & Kurt Witteman), food waste reduction (Michael Gobbel & Tom Smith), student orientation (Jessica Heinz, Claudia Remy, & Moses Viveros), and bottled water policy (Ashley Nesseler, Lacy Reyna, & Brandon Rohlwing). And if you think they look happy in this photo, wait until they’re done presenting today.

Lindsey Sharp — A Key to Unlocking Species Diversity at Lolldaiga Ranch

Lindsey Sharp — A Key to Unlocking Species Diversity at Lolldaiga Ranch

Lindsey is a senior SUST major and returning adult student who was awarded the prestigious Travis Foundation Scholarship this fall at RU, a competitive award given to 16 students each year. The scholarship enabled her to continue her studies as well as pursue a Spring 2016 internship at the Field Museum of Natural History, which she reported on recently here. Her project focuses on the preparation and identification process of specimens collected during field research in the Eastern Province of Kenya. The results of the identification process were also analyzed in order to determine the area’s population of rodent species, which can be compared to earlier samples gathered from the area in order to determine changes in biodiversity over time. Her talk will discuss her everyday work at the lab in the larger context of mammal ecology, biodiversity conservation, and the value of museum collections research.

Cassidy Avent — Summer at SCARCE: An Environmental Education Internship Experience

Cassidy Avent — Summer at SCARCE: An Environmental Education Internship Experience

Throughout the summer of 2015, SUST senior Cassidy Avent had the opportunity to work as an intern for an environmental NGO known as School and Community Assistance for Recycling and Composting Education (SCARCE). Her summer included working at the SCARCE office in Glen Ellyn IL, giving environmental education presentations at schools and community events, participating in teacher workshops, and many other fulfilling activities. Within this presentation she discusses her experience at SCARCE along with all of the valuable information and insights she gathered while interning at such a fascinating place.

Tiffany Mucci — Midewin: One Land’s Story of Recovery and Renewal

Tiffany Mucci — Midewin: One Land’s Story of Recovery and Renewal

SUST senior and returning adult student Tiffany Mucci, who has served as the Assistant Editor of the SUST at RU Blog this academic year, explores Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie as a living example of both the challenges we face in restoring and managing our native landscapes, and the resiliency of nature. Her presentation will highlight this site’s history as one of our nation’s most productive ordnance complexes to ever exist, and reveal its present-day designation as a protected tallgrass prairie ecosystem under the U.S. Forest Service. From seeding, to frogging, to corralling the newly-adopted buffalo of Midewin, she’ll relate what goes into “making a prairie” in the 21st century.

Lacy Reyna — Temporal Distribution of Bryophytes in Cook County, IL

Lacy Reyna — Temporal Distribution of Bryophytes in Cook County, IL

Senior science major and honors student Lacy Reyna, a double major in biology and psychology and RU’s 2015 Lincoln Laureate, worked in the botany division of the Field Museum while enrolled in the museum-based SUST 330 Biodiversity course this past fall with Lindsey. Using collections data from various institutions including the Field Museum, her research done in collaboration with FMNH scientists documents the shift in bryophyte species in Cook County across time. Her talk provides potential explanations for the shifts in species populations as well as discusses the importance of museum collections for biodiversity conservation.

Come join us to learn about and celebrate these students’ work! This event is free and refreshments are provided. Kindly RSVP to Mike Bryson (mbryson@roosevelt.edu) your plans to attend. Videoconferencing will be made available via Zoom. Hope to see you there! And if you need further incentive to attend, just check out past Symposia from 2013-15.

Essential Information

- Date / Time: Wednesday, Apr. 27th, 2015 / 2:30-5:45pm

- Agenda: Refreshments served and pleasant hobnobbing begins at 2pm; presentations start promptly at 2:30pm; event concludes ~ 5:30pm (with more chit-chat and eating)

- Place: RU’s Wabash Building, 425 S. Wabash Ave., Chicago IL, room 1214

- Zoom Videoconferencing: Can’t attend in person? See below!

- RSVP: SUST Director Mike Bryson (mbryson@roosevelt.edu)

Zoom Videoconference Information

- Join from PC, Mac, Linux, iOS or Android: https://roosevelt.zoom.us/j/368245293

- Or iPhone one-tap: 14086380968,368245293# or 16465588656,368245293#

- Or Telephone:

+1 877 369 0926 (US Toll Free) or +1 888 974 9888 (US Toll Free)

Meeting ID: 368 245 293

Links to past Symposia

- Symposium 1.1 (Fall 2013): Alison Breeding, Kyle Huff, Ron Taylor

- Symposium 1.2 (Spring 2014): Colleen Dennis, Jordan Ewbank, Mary Beth Radeck

- Symposium 2.1 (Spring 2015): Melanie Blume, Rebecca Quesnell, Mary Rasic, Emily Rhea

Interdisciplinarity, Sustainability, & Service Learning

A little while back, I was asked by some of my environmental studies colleagues outside of RU to briefly describe my take on interdisciplinary scholarship in under 200 words. Here’s what I came up with:

An interdisciplinary scholar can speak different disciplinary languages, recognize how they work together, and use that facility to say something unique in the process. Interdisciplinary scholarship is about integration: fitting things together in a complementary, cohesive, creative fashion so that the whole is niftier than the mere sum of its parts. I’ve sung in choirs where men and women blend the different pitches and timbres of their voices in 4, 6, even 8 part harmony. At its best, interdisciplinary work is like that: creating beautiful music from difference, even the occasional dissonance, such as in the give-and-take dialogue of interdisciplinary team-teaching. While most university landscapes remain dominated by disciplinary silos, interdisciplinary teaching and scholarship open up new ground for discovery and connect faculty and students working on problems of mutual interest.

The last few years I’ve taught in and directed the Sustainability Studies program here at Roosevelt, the curriculum for which was designed in a consciously interdisciplinary fashion to integrate methods and insights from the natural and social sciences as well as the arts and humanities. My own academic background in biology and literature, as well as my many years of working within a multidisciplinary faculty teaching general education to returning adult students in RU’s College of Professional Studies, means I have keen interest in integrating knowledge and research methods from the humanities and natural sciences — something that is an excellent fit within the inherently interdisciplinary endeavors of environmental studies and the newly emerging sustainability studies. In a previous post, I reflect on the relevance/importance of the arts and humanities to matters of environmental science and policy.

Another thought is that service learning provides a powerful vehicle for interdisciplinary teaching and learning — both within the context of a single (potentially interdisciplinary) class as well as in the collaboration of two or more courses from different academic departments. A fascinating model for this is the Sustainable City Year Program, pioneered recently by the University of Oregon and spun off in various ways by other US colleges and universities. This is an action-oriented and sustainability-directed approach to interdisciplinary learning and scholarship that can be tailored to the particular strengths and capacities of a given university.

Sustainability and Biodiversity at the Field Museum

Last Monday, as a warm 60+ degree (F) day enveloped downtown Chicago in a splendid preview of spring, my students and I hiked from Roosevelt’s Gage Building in the Loop to the lakefront, where we strolled southward to that great edifice of natural history and biodiversity, the Field Museum. Once there, we met up with Carter O’Brien, the Museum’s sustainability manager (who basically created the job over a number of years after spearheading the FMNH’s recycling program). Carter gave us a comprehensive walking tour of the museum’s grounds, community garden, and loading dock.

Along with many of staff and researchers at the FMNH, Carter has spearheaded the museum’s efforts to green its practices in energy consumption, waste management, food service, recycling, transportation, exhibit design, and gardening. Despite being an institution dedicated to studying and conserving the world’s rich trove of biodiversity, the Field Museum until recently was not at all sustainable in its own operations, an irony not lost on environmental advocates such as Carter and many of his museum colleagues. Now the FMNH is a recognized leader in transforming old buildings into sustainably-managed facilities, as it recently garnered a LEED Gold rating on its operations and maintenance from the US Green Building Council, only the 2nd existing museum building in the US to do so, and it has just received a $2 million grant to redevelop its grounds within Chicago’s famed Museum Campus in ways that enhance biodiversity, water conservation, and public education.

Carter brought us inside through the seemingly ancient (and surprisingly small) loading dock, thorough a phalanx of heavy doors, narrow passageways, and claustrophobic elevators (all part of the FM’s 19th Century charm), and to the Botany research division, one of the four major research/collections areas of the museum. There we met up with the equally ebullient Dr. Matt Von Konrat, who has many titles at the museum but is best known as an early land plant botanist (which means he studies mosses and liverworts both here and abroad) and the Head of Botanical Collections at the museum.

Dr. Von Konrat was kind enough to set up a sampling of preserved plant specimens from the Museum’s vast collection, which when arrayed on a huge wooden table represented a journey of 500 million years of land plant evolution. Many of these examples had special significance as type specimens, which are recognized as being archetypal examples of the species that are used for benchmarking certain key identifying characteristics.

One plant, a particularly tiny moss, held special significance in a recent court case about Burr Oak Cemetery scandal in the far South Side Chicago neighborhood of Dunning. Cemetery caretakers dug up several hundred human remains and dumped them in a mass grave in order to sell additional plots in the cemetery over a several year period. The moss was part of forensic evidence analyzed by Dr. Von Konrat that proved the involvement of cemetery employees in this heinous crime. The story illustrates the profoundly important role that environmental evidence can play in forensics, and the potential value in aligning the study of botany (and sustainability) with that of criminal justice.

After both of these splendid tours, my students and I ventured forth into the public area of the museum — its exhibits, naturally! — where we inspected the notable (and LEED Gold certified) conservation exhibit, Restoring Earth, which documents FMNH efforts to conserve natural and human communities in South America as well as restore local prairie, woodland, and wetland ecosystems here in the Chicago region.

Water, Climate Change, Science, & Literature

This month one of Chicago’s public radio stations, WBEZ (91.5 FM), has kicked off a fascinating and timely series about water, science, and the humanities. It’s called After Water, and according to the series’ website, the project asks “writers to peer into the future—100 years or more—and imagine the region around the Great Lakes, when water scarcity is a dominant social issue. It’s a cosmic blend of art and science . . . [that will feature] stories, research, photos and more.”

Kicking off the series this week was a Morning Shift conversation on WBEZ with my longtime Roosevelt colleague, Dr. Gary Wolfe (the guy who hired me, by the way), one of the world’s foremost authorities on the literature of sci-fi and fantasy. Gary was in the house to talk about the emergent genre of “cli-fi,” or fiction about climate change, and its relation to water issues. Not only was Gary completely at home in this milieu due to his many years’ experience doing his own radio show in Chicago, “Interface,” but this gig was an apt follow-up to his teaching of a Special Topics SUST 390 seminar this past spring entitled “Sustainability in Film and Fiction.”

I look forward to following the stories and images within this unfolding After Water series, as it’s a great example of the need to integrate science and the humanities in constructing compelling narratives about the crisis of climate change, a subject I addressed briefly in this short essay from last summer.

June 2014 Guest Talks and Conference Presentations

The first part of June has been exceptionally chatty, academically speaking, as I think I’ve had my busiest week ever in my 20-year academic career giving presentations and hobnobbing with colleagues at other institutions. Thus far I’ve been right here in the Chicago area, though a nice little trip to New York City awaits later this week — which is exciting, since I haven’t been to New York since the fall of 2006 (for the SLSA Conference at NYU).

Last Sunday, as we flipped the home calendars to June, I drove out to Joliet Junior College, the nation’s oldest community college, to give a guest lecture entitled “Sustainability and the Future of Cities: Connecting Curriculum to Community” (pdf), as part of JJC’s three-day faculty retreat for the Grand Prairie Project — an effort to encourage the integration of sustainability across JJC’s curriculum led by my colleague, friend, and fellow Joliet public school alum Maria Rafac, an architectural technology prof at the college.

Then on Wednesday, June 4th, I collaborated with an RU professor, Aaron Shoults-Wilson, on a presentation (pdf) about sustainability/environmental science education at Roosevelt for a “Research and Education towards Sustainability Symposium” sponsored by the Institute for Environmental Sustainability at Loyola University in Chicago. This small gathering was especially interesting, since the IES was hosting a group of Vietnamese environmental scientists and educators from Vietnam National University. Learning about their work in Ho Chih Min City and other locations throughout Vietnam was utterly fascinating, and they in turn were extremely excited by the chance to explore Chicago and meet like-minded colleagues here in the US. I also got my first tour of Loyola’s new IES facility in my old neighborhood of East Rogers Park, opened in Fall 2013, which is quite impressive indeed.

Finally, on Thursday, June 5th, I gave my first talk at the Field Museum of Natural History along the downtown Chicago lakefront, as part of the museum’s Interchange monthly lecture series sponsored by the Dept. of Science and Education. These gatherings are internal to the museum, and provide a chance for researchers to present data and report on works in progress from all the various disciplines of the museum in a friendly setting that encourages active discussion and cross-disciplinary connections. My talk, “Reading the Book of Nature: May Theilgaard Watts’ Art of Ecology,” (pdf), reflected on how the arts and humanities complement scientific discourse, in this case within the context of urban ecosystems wherein live over 80% of Americans and more than 50% of people worldwide.

Later this week, I fly to New York City for the annual conference of the Association for Environmental Studies and Sciences, one of the academic tribes of which I’m an enthusiastic member. Hosted this year by Pace University in lower Manhattan, near the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, the conference theme is “Welcome to the Anthropocene: From Global Challenge to Plantery Stewardship.” This smallish conference of 500-600 attendees is always notable for its friendly and informal atmosphere, great spirit of convivial networking among colleagues from many different areas of academia (from the sciences to the social sciences to the humanities), and fun field excursions. My talk about my teaching experiences in a service-learning course at the Chicago Lights Urban Farm is part of a panel entitled “Innovative Pedagogies for Environmental Justice and Community Engagement.” I’m eager to hear what my fellow panelists have in store for our session!