Photographs by Brad Temkin

Photographs by Brad Temkin

February 9 – May 6, 2017

Opening reception and talk by Brad Temkin

Thursday, February 9th, 5-7 p.m.

Roosevelt University’s Gage Gallery

18 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago IL

(312) 341-6458

Statement from the Artist

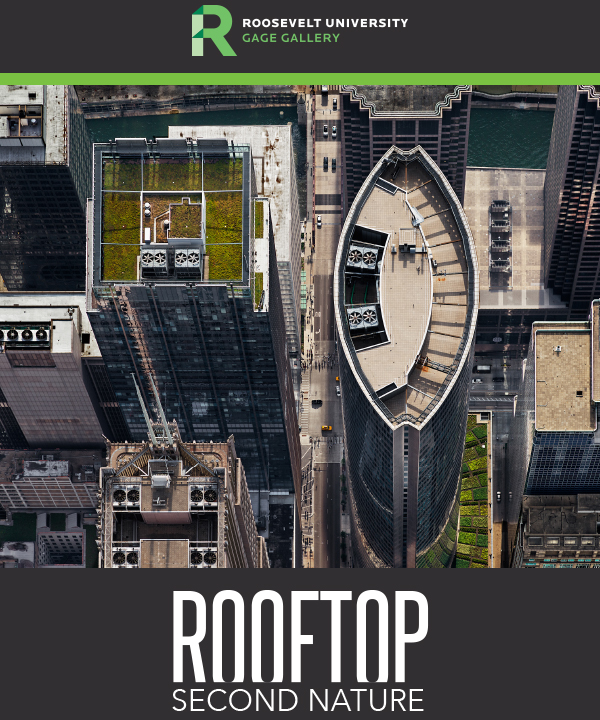

“Rooftop: Second Nature draws poetic attention to an important new movement to counter the heat island effect caused by city life. Green roofs reduce our carbon footprint and improve storm water control, but they do far more. They reflect the conflict of our existence, symbolizing the allure of nature in the face of our continuing urban sprawl.

“My images do more than merely document rooftop gardens. By securely situating the gardens within the steel, stone, and glass rectangularity of urban downtowns, I ask viewers to revel in their far more open patterns, colors, and connection to the sky. In this break, I see not merely beauty and dichotomy, but the framework for positive change.”

— Brad Temkin

On Urban Ecology, Green Rooftops, and the Sustainability of Cities

Exhibit Essay for Rooftop: Second Nature, Roosevelt University, Spring 2017

What does a sustainable city look like? Solar panel arrays, bike lanes along busy thoroughfares, and urban farms converted from vacant lots all come to mind; but the iconic symbol of the contemporary green metropolis is the green rooftop. Though mostly invisible to us at ground level, these living surfaces embody key chacteristics of the urban ecosystem even as they serve as sustainability badges of honor for environmentally-minded civic leaders.

The science of urban ecology demonstrates that cities are not mere technological constructions, distinct from and diametrically opposed to nature, but complex ecosystems constituted by energy flows and waste sinks, evolving communities of organisms, and habitats both natural and designed. The green rooftops that increasingly dot the skylines of 21st-century cities are engineered to serve specific ecological, economic, and/or aesthetic functions for the buildings they crown and the people who inhabit them. Such spaces are simultaneously technological and natural: well-ordered assemblages of soil, plants, and micro-organisms that soften the surfaces and round the edges of the rectilinear built environment.

Said rooftops also are prime examples of green infrastructure, a critically important element of the urban fabric. Parklands and nature preserves, wetlands and riparian zones, bioswales and rain gardens, farm lots and backyard gardens, and green rooftops — all comprise a city’s green infrastructure. These diverse physical spaces provide a myriad of ecosystem services: they conserve freshwater resources, reduce energy consumption, mitigate air and water pollution, create wildlife habitat, and enable our own physical contact with nature.

The dramatic images in Rooftop: Second Nature are striking visual compositions that reveal the city from a different and unfamiliar angle, as well as information-rich object lessons in how green infrastructure enhances urban sustainability. Within one roof’s environs, a diverse riot of native prairie plants is juxtaposed with the boxy lines of air conditioning units, while other images expand the frame beyond the rooftop’s edge to portray its larger context, such as Chicago’s street grid bisected by its namesake river.

Such visual elements evoke the entanglement of ecological cycles in which the roof participates. These living surfaces provide superior building insulation, thus reducing heating and cooling costs and, in turn, decreasing carbon emissions. Plants evapotranspire water, which cools the micro-climate of the building’s exterior, thus mitigating the urban heat island effect. Precipitation falling on these rooftops is not wasted as runoff to an energy-intensive sewer and wastewater treatment system; rather, it is captured in place, absorbed by the resident plant community, and returned to the atmosphere in a silent yet eloquent demonstration of the water cycle.

Brad Temkin’s photographs are densely layered with meaning and invite inquiry from the viewer: From what vantage point was that shot taken? What are beehives doing on a skyscraper roof? How is this largely unseen rooftop relevant to the river flowing only two blocks away? Who has access to these spaces, and what psychological benefits might accrue from exploring them? Such questions suggest the dynamic interplay between art and science within our perceptions of the sustainable city.

— Michael A. Bryson