Twenty-five years ago, I had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to travel to Antarctica as part of a scientific research expedition from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Taking a semester’s leave from my graduate studies at SUNY Stony Brook, I worked for two months as a field technician and writer-in-residence on a team researching the biogeochemistry of Lake Fryxell, a permanently frozen-over lake in Antarctica’s Dry Valleys. This extraordinary experience was memorable in many ways, including a brief three-day stopover in New Zealand, where we made our final preparations at the US Antarctic Program’s headquarters in Christchurch before flying to McMurdo Station on the Ross Ice Shelf.

Now as a mid-career academic seeking new challenges and opportunities beyond my Midwestern home at the southern rim of the Great Lakes — and having traveled outside the US (to Canada) only twice during this time — I decided to apply for a Fulbright Scholar fellowship to explore a distant locale that has always resonated powerfully in my memory. But this time, instead of a mere fleeting taste of Christchurch and a brief fly-over of the North and South Islands, I hope to spend several months in 2018 researching, writing, and living in New Zealand, based at Lincoln University a few kilometers outside of Christchurch, in order to enrich my understanding of urban river ecosystems as well as gain a much-needed global perspective on my scholarship and teaching.

Now as a mid-career academic seeking new challenges and opportunities beyond my Midwestern home at the southern rim of the Great Lakes — and having traveled outside the US (to Canada) only twice during this time — I decided to apply for a Fulbright Scholar fellowship to explore a distant locale that has always resonated powerfully in my memory. But this time, instead of a mere fleeting taste of Christchurch and a brief fly-over of the North and South Islands, I hope to spend several months in 2018 researching, writing, and living in New Zealand, based at Lincoln University a few kilometers outside of Christchurch, in order to enrich my understanding of urban river ecosystems as well as gain a much-needed global perspective on my scholarship and teaching.

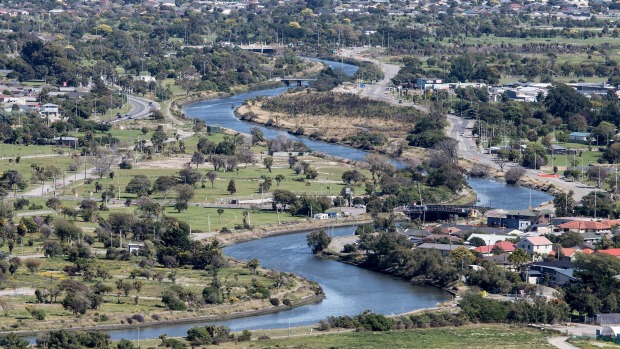

Objectives and Methodology: My proposed project focuses on the Otakaro-Avon River that flows through Christchurch, NZ, as a natural and human ecosystem undergoing stress and change. The Otakaro-Avon is an important focal point of urban sustainability planning and ecological restoration. Using the qualitative research framework of the environmental humanities, which blends insights and analytic methods from literary studies, environmental history, ecology, and other disciplines, I plan to undertake an ecocritical study of this urban river’s history, present condition, and future prospects in the context of urban redevelopment underway after the 2011 earthquake that devastated Christchurch and many of its suburbs. This place- and observation-based perspective on the Otakaro-Avon watershed merges humanistic scholarship with physical exploration of the river as a highly modified, impaired, yet still biologically rich ecosystem with great sociocultural significance.

I will examine a wide range of “water stories” focused on the river — from historical documents to scientific analyses to technical reports — as well as current representations of the river in post-earthquake planning documents and journalistic accounts; conservationist, community-based, and indigenous discourse; plans for memorials and sustainable redevelopment along the river; and works of literature, film, and online media. This research will influence the crafting of my own stories of the Otakaro-Avon River and its fluid future, based on my in-the-field observations and experiences, in both narrative forms suitable for general readers as well as in scholarly prose for academic audiences — much as I have done in my recent work on the Chicago River‘s history, ecology, and future sustainability.

Key questions to be addressed in this project include but are not limited to:

- How has the Otakaro-Avon River been utilized, modified, polluted, exploited, abused, defended, etc. over time? How does the history, quality, and character of the river inform people’s relationship to its present state and future prospects?

- In what ways is the river important, economically and culturally, to the Maori indigenous people (as mahinga kai, a food-gathering place) as well as New Zealanders of European descent? How do people in Otakaro-Avon River’s watershed connect to the waterway? What kinds of activities do they undertake in terms of recreation, industry, and conservation?

- What role do the river’s conservation and restoration have in the ongoing redevelopment of Christchurch’s Red Zone and within the city’s future sustainability?

- How do the above issues intersect with questions of environmental justice, especially with respect to toxic pollution, public access to water resources and open space, and iwi (indigenous people) living with the Otakaro-Avon River watershed?

As an interdisciplinary-minded scholar within the environmental humanities, I employ a qualitative research approach. Using the analytic tools of ecocriticism, I emphasize the close reading and analysis of individual texts, their relationships with one another, and their place in the broad contexts of scientific discourse, nature writing, environmental history, and sustainability. At root, my work starts from the premises that the urban environment (both built and natural) is a worthy object of study; that natural resources are imperiled and therefore in need of protection and conservation; and that humanistic inquiry about the myriad relationships between humanity and nature in cities can foster, in the long run, ecological awareness and environmental progress.

Academic and Professional Context: Urban rivers are many things simultaneously: corridors of biodiversity, green infrastructure for storm water retention, transportation arteries for commerce, waste sinks, places of human recreation, and sites of environmental restoration. This partial list illustrates their dual nature: waterways in cities are all too often heavily polluted, modified, and abused ecosystems that bear scant resemblance to their former selves. They function as receptacles of waste and servants of commerce/industry, at the expense of water quality and biodiversity; and in many cases, city dwellers are physically as well as culturally cut off from access to waterways.

Yet urban rivers also harbor tremendous renrenga ropi (biodiversity) and exhibit a capacity to connect citizens to the natural world that exists cheek-by-jowl with the built environment as well as to their cities’ natural and cultural histories. In this sense, damaged urban water systems are pathways of connection that can foster a sense of place vital to building an environmental ethic of care among city dwellers.

Geographers, urban ecologists, environmental scientists, and sustainability scholars are assessing waterways as a critical component of urban ecosystems. Given that cities consume energy and resources from far beyond their geographic boundaries and produce high levels of waste as well as greenhouse gases, their future sustainability depends upon large-scale actions such as repairing water/wastewater infrastructure, conserving energy, improving transportation access and efficiency, enhancing biodiversity, and reducing material waste.

Such goals are complicated and made urgent by the destructiveness of natural disasters. The 2011 Christchurch earthquake provides a monumental challenge as well as golden opportunity for inclusive and socially just urban planning that embraces environmental sustainability as a central goal. Unsurprisingly, the Otakaro-Avon River is prominent within this planning and rebuilding process (and illustrative of its many challenges).

More broadly, urban rivers provide a specific context for assessing the impacts of global urbanization on human relationships to nature. As of 2015, over 50% of the world’s population is urban; in the US and NZ, that figure is 82% and 86%, respectively, according to the World Bank. A consequence of this is a pervasive (though hardly universal) alienation from the natural world of urban citizens. River systems constitute important natural resources where people can have direct and meaningful contact with nature close to where they live.

The stories we tell about cities and rivers are a means of grappling with the ideas and questions noted above. While the natural and social sciences generate vital empirical data on urban rivers, the role of the arts and humanities is uniquely critical to understanding urban waterways and our relationships to them. Our “water stories” are both a means of representing our values and history as well as a method of critique. The fundamental power of storytelling within human experience points to the impact of artistic expression and humanistic analysis on understanding the importance of waterways within urban ecosystems and human communities.

Significance of Study: Understanding the role of water in urban ecosystems is vital to improving the resilience of cities (e.g., protecting people and property from floods and other environmental disasters) and making them more sustainable (e.g., improving water retention and quality through expansion of green infrastructure). Cities are where most people in the world now live, a trend that will continue in coming decades as we grapple with the impacts of climate change, water quality degradation, toxic pollution, and environmental injustice. As a vital resource for all human communities, water is an important node of inquiry within environmental science and, more broadly, sustainability studies.

Urban rivers (and their watersheds, which include tributaries, wetlands, and estuaries) are ideal barometers of the ecological and socio-cultural health of our cities as well as our attitudes about and connections to the natural world. The Otakaro-Avon River is one of New Zealand’s most polluted waterways and, at the same time, one of its most important — both ecologically and symbolically — given the high number of people who live and work within its watershed and its centrality within the city’s earthquake recovery process.

Enhancing our knowledge, awareness, and appreciation of the river’s status and value is vital to its remediation and restoration as a living ecosystem that is not just an integral part of Christchurch’s green infrastructure, but also a significant thread within the city’s historical and cultural fabric. My research will explore how stories have defined the Otakaro-Avon River thus far, and how new ones might shape its sustainable future.

Why New Zealand? As an island country distinguished by highly diverse ecosystems, small and large cities, a vibrant indigenous culture, famously productive agricultural lands, longstanding conservation values, and threatened ecosystems and natural resources, New Zealand is a remarkable laboratory for exploring questions of environmental sustainability in the early 21st century.

Possessing a uniquely complex postcolonial mix of people from indigenous Maori (tangata whenua), European, and trans-Pacific Island cultures, New Zealand is progressive in its formal and structural recognition of indigenous rights, which has important implications for urban sustainable development and environmental conservation. More locally, Christchurch is a vitally important urban center: not only is it the biggest city on the South Island (pop. ~366,000), but its ongoing efforts to recover from the devastating earthquake in 2011 make it a test case for how cities can respond to natural disasters and seize opportunities to improve the sustainability of urban infrastructure, revitalize waterways, increase open space, enhance biodiversity, and involve the citizenry within the ongoing planning and reconstruction process.

Lincoln University: An incredible wealth of people and resources exist in and around Christchurch that would be invaluable to me as a scholar and writer. The Faculty of Environment, Society, and Design and its Department of Environmental Management at Lincoln University — a land-based institution located near Christchurch with a phenomenal array of environmental academic programs and research centres — offer an interdisciplinary community of scholars and teachers dedicated to environmental research and sustainability education.

LU’s Centre of Land, Environment, and People (LEaP), which is closely affiliated with the aforementioned Faculty, provides an intellectual home for research and collaboration with scholars and students from diverse disciplines spanning the natural/social sciences, the humanities, and various technical fields. Additionally, the Waterways Centre for Freshwater Management, a research collaboration between LU and the University of Canterbury, has published a wealth of technical reports on water resources throughout the Christchurch metro area and the Canterbury region, and would be an invaluable resource for advice and collaboration.