Please share this pdf version of the event flier!

Please share this pdf version of the event flier!

Category: Politics

Seeking Volunteers for Voter Registration Drive on 2/12

Remembering Lee Botts (1928-2019), Environmental Activist, Champion of the Great Lakes and Indiana Dunes

While Millennials and Gen Zers are leading the way on climate change activism and environmental justice here in 2019, their passion for change and stalwart efforts against seemingly insurmountable barriers are inspired by and built upon the efforts of previous generations of environmental advocates. On such champion — local conservationist, activist, writer, editor, film documentarian, and policymaker Lee Botts (1928-2019) — died this past Saturday in Oak Park, IL.

According to the tribute to Botts posted in the Hyde Park Herald, for which she wrote a garden column in the late ’50s and later served as editor from 1966-69:

“Lee Botts was editor of the Herald during the late 1960s implementation of the urban renewal plans,” said Herald Chairman Bruce Sagan, who has owned the newspaper since 1953. “Her objective journalism was a crucial component of the civic discussion during that complex history.”

In 1968, she joined the staff of the Open Lands Project in Chicago. From 1971 to 1975, she was the founding executive director of the Lake Michigan Federation, which is today the Alliance for the Great Lakes. Under Botts’ leadership, the new organization persuaded Mayor Richard J. Daley to have Chicago become the first Great Lakes city to ban phosphates in laundry detergents, led U.S. advocacy for the first binational Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in 1972, was a key advocate for the landmark federal Clean Water Act of 1972 and played a key role in persuading Congress to ban PCBs via the 1974 Toxic Chemicals Control Act.

After a short stint with the Environmental Protection Agency Region 5 office in Chicago, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to head to the Great Lakes Basin Commission in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1977. After the agency was eliminated from the federal budget, Botts held a research faculty appointment at Northwestern University from 1981 to 1985.

She joined the senior staff of Mayor Harold Washington in 1985, organizing the city’s first-ever Department of the Environment. In 1986, with Washington’s endorsement and support, Botts ran for the board of the Metropolitan Sanitary District of Greater Chicago but lost by 2%.

Botts relocated to Northwest Indiana in 1988, where she became an adjunct professor at a local college and joined various boards and committees. While living in Gary’s Miller Beach neighborhood, she began advocating for an idea she’d first written about a quarter-century earlier: the Indiana Dunes Environmental Learning Center, which she helped found in 1997.

An independent non-profit located within Indiana Dunes National Park, the Dunes Learning Center offers year-round environmental education programs and overnight nature-camp experiences for grade-school students and teachers. Today, nearly 10,000 students come to the center each year from school systems throughout Indiana, Michigan and Illinois. Botts initially chaired the institution’s board of directors.

For many years, Botts suggested that the modern history of the Indiana Dunes region could become an engaging documentary film. With director Patricia Wisniewski, she began working on making “Lee’s dunes film” in 2010, writing the film’s script, conducting many of the interviews, leading the fundraising effort and traveling to promote the project, even after she was no longer able to drive her own car.

“Shifting Sands: On The Path To Sustainability” was released in 2016 and won a regional Emmy Award. To date, it has been broadcast on more than 70 public-television stations, included in several major film festivals and screened by scores of local citizens’ groups and public libraries throughout the states bordering Lake Michigan.

Botts was awarded a citation from the United Nations Environmental Program for making a difference for the global environment in 1987, the 2008 Gerald I. Lamkin Award from the Society of Innovators at Purdue University Northwest and honorary doctorates from Indiana University and Calumet College of St. Joseph. She was inducted into the Indiana Conservation Hall of Fame in 2009.

A person who did any one of the above accomplishments would rightly be lauded for the impact of their work on behalf of people and the environment. The fact that Lee Botts did all this and more — through her own will, dedication, and fierce advocacy as well as her ability to connect and collaborate with others — is nothing short of astounding.

See these sources for more information on Lee Botts:

Environmentalist and former Herald editor Leila “Lee” Botts dies at 91 (Hyde Park Herald)

Lee Botts’ children reflect on her life as pioneering environmentalist, advocate for the Great Lakes (The Times, NY Indiana)

Environmentalist, journalist and documentarian Lee Botts of Gary dead at age 91 (Post-Tribune)

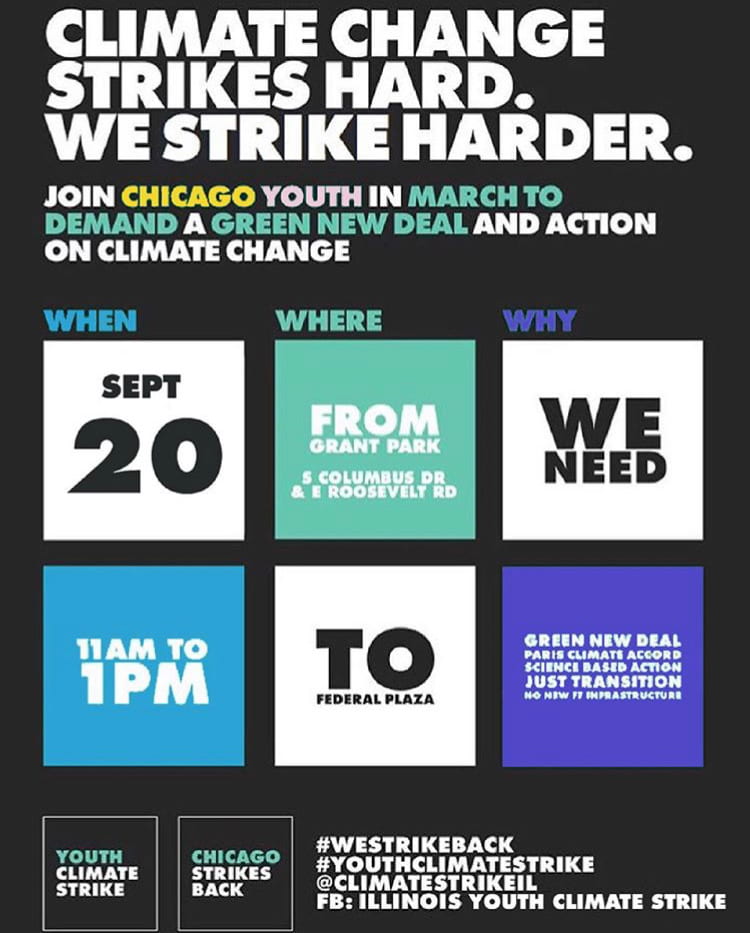

Chicago Youth Climate Strike: Fri 9/20/19 in Grant Park

Join members of RU Green, the Math Club, and others in an all-ages Chicago Youth Climate Strike march in Grant Park in downtown Chicago this Friday 9/20/19 in solidarity with climate strike marchers all over the world. Options for meeting:

Join members of RU Green, the Math Club, and others in an all-ages Chicago Youth Climate Strike march in Grant Park in downtown Chicago this Friday 9/20/19 in solidarity with climate strike marchers all over the world. Options for meeting:

- 10:30am WB Lobby, 425 S. Wabash Ave., then walk with RU Green to Grant Park

- 11:00am, south end of Grant Park (Roosevelt & Columbus)

RU students, want to help make signs? Join RU Green outside the CSI office (WB 3rd floor) on Wed 9/18 @5pm. Bring your own poster-making supplies if you have ’em (supplies limited).

Questions? Email RU Green prez Samantha Schultz (sschultz10@mail.roosevelt.edu).

Planning for Environmental Justice: Kim Wasserman @RooseveltU, Wed 9/26

Save the Fen at Joliet Junior College: An Open Letter

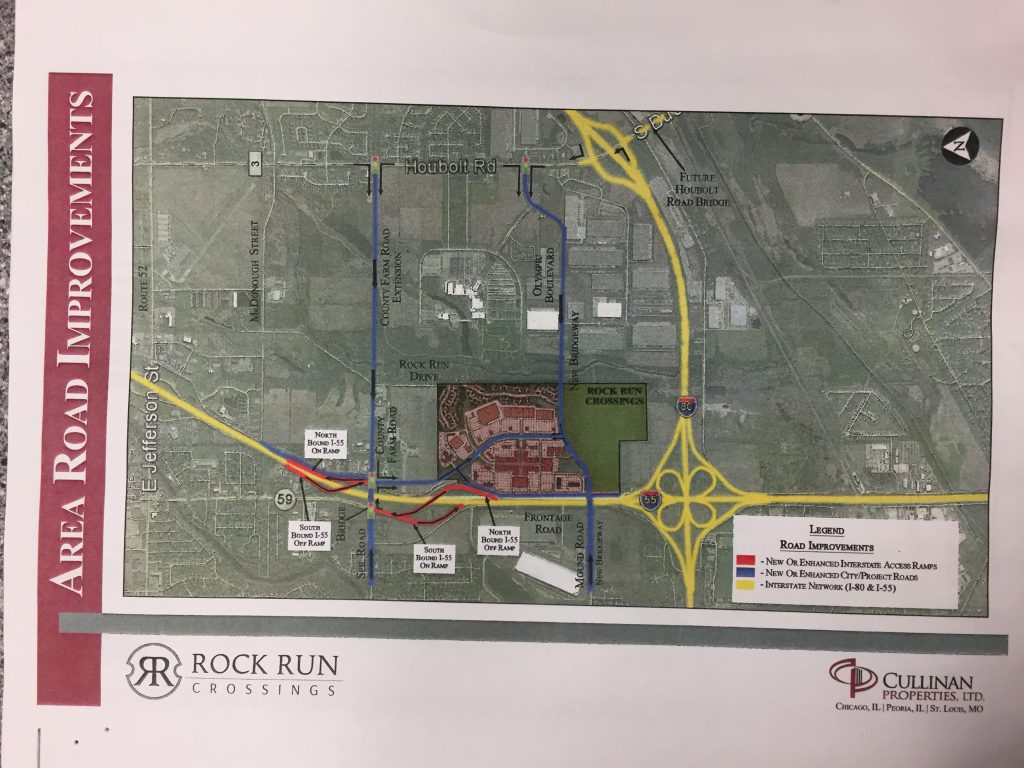

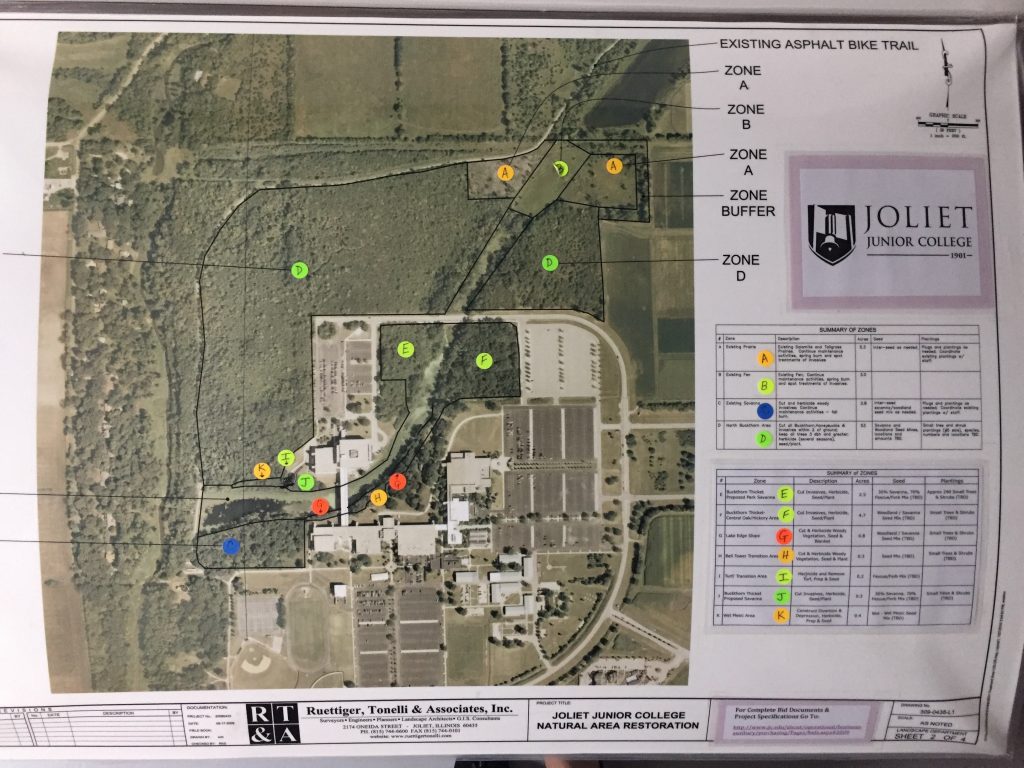

This is an open letter I wrote recently to the leadership of Joliet Junior College in my hometown of Joliet, Illinois. The issue at hand is a future road extension, proposed by a mall developer, that would bisect the protected natural areas of the JJC Campus and compromise a rare type of Illinois wetland. The proposed roadway has galvanized support for the JJC Fen and associated natural areas on campus and in the Joliet community, as the College’s Board of Trustees debates how to proceed.

13 June 2017

Dear President Judy Mitchell and Board Chairman Bob Wunderlich –

I write to you today as a citizen of Joliet, a longtime environmental educator, and the son and grandson of JJC graduates. My overall message to you and your colleagues on the JJC Board of Trustees is simple: I strongly support the view of the JJC Natural Areas Committee and numerous faculty, students, alumni, and community members that the JJC Fen and associated open/natural areas must be protected from the proposed road extension by Cullinan Properties.

Since its settlement began in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Illinois has lost over 90% of its natural wetlands to agricultural and urban development. In the meantime, it has built what must be millions of miles of roads, many of which are deteriorated and no longer in use. In short: we have enough roads. We cannot afford to lose yet more high quality wetlands.

As the above map illustrates, the proposed County Road Extension is neither the shortest nor the most convenient traffic route from the adjacent I-55 and I-80 interstates to Cullinan’s proposed “mixed-use lifestyle center” — yet even if it were, it would not be the best route. As the great writer, ecologist, and conservationist Aldo Leopold famously wrote in his 1949 book A Sand County Almanac, “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise” (pp. 224-5).

The importance of JJC’s high quality open spaces, biodiversity, water quality, landscape aesthetics, and overall campus sustainability far outweigh the supposed advantages of this road extension, which serves no other purpose than to direct traffic to a shopping center that could otherwise take several other perfectly viable alternative routes that are faster and more direct.

As the College mulls over the tempting overtures of Cullinan Properties and decides whether to protect this ecologically and educationally valuable ecosystem, or to allow its fragmentation and ultimate degradation, I urge you and your colleagues to take a long view of the matter. A perspective informed by environmental sustainability inspires us to ask careful questions about the road, the character of the campus, and the institutional mission — questions that relate not just to the issues of the day, but those decades into the future.

We now live in a world of rapid urbanization, climate change, and accelerating species extinction. A century from now, I highly doubt that the leaders, faculty, students, and alumni of JJC will look favorably upon a decision in 2017 to disturb and degrade its coveted and protected natural areas with a road built exclusively to service a single shopping center. In fact, given the economic vagaries that occur over a mere 20-30 years, let alone a century, it’s questionable said development will even be operating that far into the future. (The example of the Jefferson Square Mall, built in 1975 with great fanfare and now vaporized from the landscape a mere 40 years later, comes to mind, though there are many others one could cite.)

However, I do think that the future stewards of America’s first and oldest community college (founded 1901) would be rightly proud in the year 2117 that its leaders in the present day chose to maintain the ecological and aesthetic integrity of the campus ecosystem by conserving its tranquil and species-rich open space, protecting the water quality of its beautiful lake and stream, and ensuring the opportunities of generations of students to study field-based biology and ecology in the extraordinary “living classroom” provided by one of Illinois’ most rare and endangered wetlands, a fen.

As a graduate of the local public schools (JT West class of 1985), a current resident of Joliet, and now a professor of sustainability studies at Roosevelt University in Chicago, I have developed a close relationship over the past 12 years with many students and faculty at JJC. I can attest from my vantage point in the regional higher ed community that JJC’s commitment to environmental sustainability – embodied in its native woodland, prairie, and wetland ecosystems; its 1998 Natural Areas Resolution; its LEED-Platinum greenhouse facility and widely-praised arboretum; its progressive academic programming; and its campus sustainability leadership – is the envy of many colleges and universities in the Chicagoland region.

Consequently, harming the fundamental character of the campus’ rare and biodiverse ecosystems would not just diminish the quality of the College’s outdoor learning laboratories; it would also directly contradict JJC’s professed commitment to sustainability and potentially erode its hard-won reputation among its institutional peers.

As a local citizen who cares deeply about and greatly appreciates JJC’s remarkable history and unique educational mission, I ask that you heed the recommendations of the Natural Areas Committee and protect said Natural Areas, including the fen, from any present or future road development.

Yours sincerely,

Mike Bryson

Resident of Joliet, IL

Professor & Director of Sustainability Studies, Roosevelt University

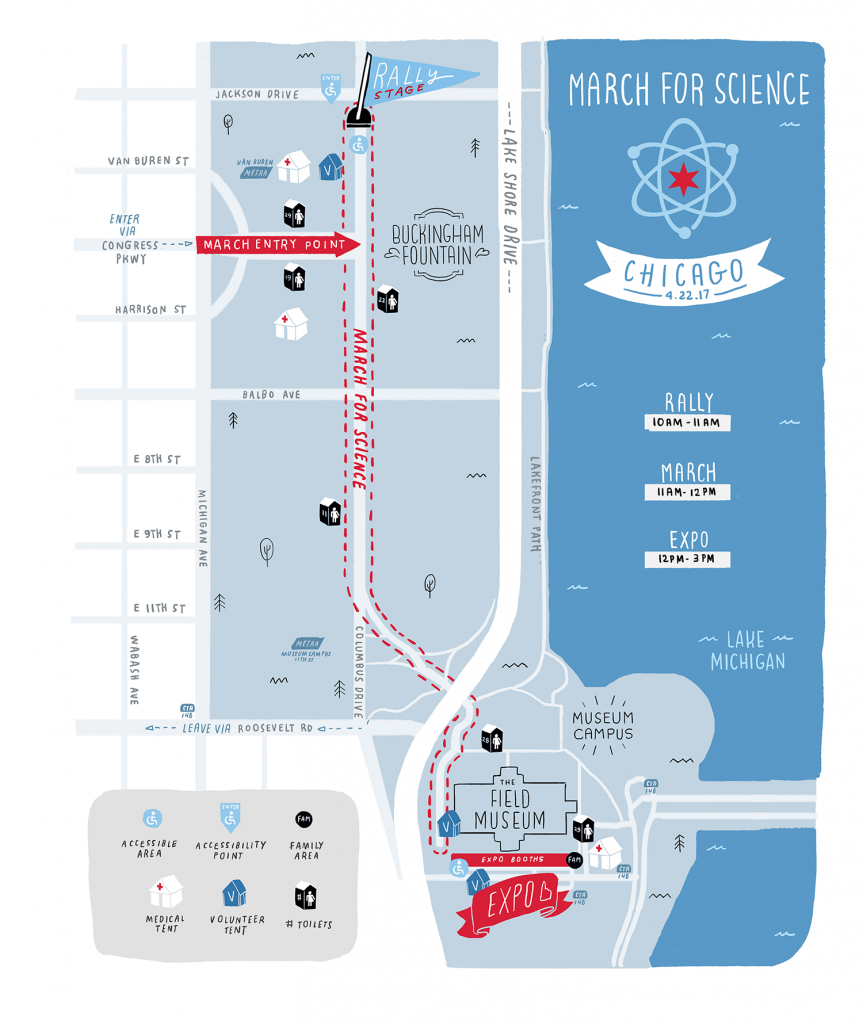

Earth Day 2017: Mapping the March for Science in Chicago! #MFSChi @sciencemarchchi

March for Science in Chicago on Earth Day 4/22

Join faculty and students from Roosevelt’s SUST program and the Department of Biology, Chemistry, and Physical Science as we in the RU community march for science! We’ll meet in the WB Lobby at 9:00am, after which we’ll walk over to Grant Park in time for the 10am rally that kicks off the day’s events. After a round of speakers, participants will march at 11am from Grant Park to the Museum Campus for a cool science expo planned for 12-3pm outside the Field Museum. Official visitor and registration details here.

Join faculty and students from Roosevelt’s SUST program and the Department of Biology, Chemistry, and Physical Science as we in the RU community march for science! We’ll meet in the WB Lobby at 9:00am, after which we’ll walk over to Grant Park in time for the 10am rally that kicks off the day’s events. After a round of speakers, participants will march at 11am from Grant Park to the Museum Campus for a cool science expo planned for 12-3pm outside the Field Museum. Official visitor and registration details here.

Introducing “Rooftop: Second Nature” — Remarks at the Opening Reception, 9 Feb. 2017

Nature within the urban landscape is simultaneously close at hand and hidden from view — a paradox of proximal obscurity. Yet its myriad forms are as diverse in kind as their human denizens. City parks, urban farms, back yards, forest preserves, vacant lots, and green rooftops — all these and more comprise the spaces of urban nature.

Despite the ubiquity and diversity of urban nature, it remains largely invisible to and thus unappreciated by many city dwellers. We are much more likely to assume nature exists “out there,” away from our cities and suburbs — especially in remote places characterized by few people and sublime landforms. An implicit corollary to that is that the city is unnatural.

Yet the recent coinage of the seemingly oxymoronic phrase urban wilderness signals that we have begun to re-envision the role of nature within metropolitan landscapes. This nature is almost always hybrid in character, a product of human design and action even when appearing “natural” in outward form. Consider our location right here, along the southwestern rim of Lake Michigan — where the surveyor’s grid was laid down upon the marshy prairie, a river’s current audaciously reversed, and lakefront parkland perched atop thousands of tons of landfill.

The intersections of the made and the natural can be apprehended in such settings . . . if one observes carefully, knows where to look, and possesses a spirit of exploration. The dramatic roofscapes by Brad Temkin in Rooftop: Second Nature are striking visual compositions that reveal the city from a different and unfamiliar angle, as well as information-rich object lessons in how green infrastructure enhances urban sustainability.

The intersections of the made and the natural can be apprehended in such settings . . . if one observes carefully, knows where to look, and possesses a spirit of exploration. The dramatic roofscapes by Brad Temkin in Rooftop: Second Nature are striking visual compositions that reveal the city from a different and unfamiliar angle, as well as information-rich object lessons in how green infrastructure enhances urban sustainability.

More broadly, though, this exhibit speaks to the vital role played by the environmental arts and humanities in envisioning a more sustainable future for humanity as well as for the millions of fellow species on our beautiful yet vulnerable planet. Thought-provoking ideas, artwork, architecture, poetry, stories, historical accounts, theater, music, and film are necessary complements to painstaking ecological analysis and pragmatic environmental policy.

Why? Because ideas and vision matter. Compelling narratives, whether literary or visual, can animate science, challenge our use of technology, inspire policy, and change hearts and minds. Such narratives must guide our thinking to ensure that social equity and environmental justice are not trampled in the relentless pursuit of short-term profits from, say, building oil pipelines across sources of drinking water in the Great Plains; or dumping the “overburden” of mountaintops into the creeks and rivers of Appalachian coal country; or selling more Pepsi or iPhones.

Skeptics of climate change cannot be persuaded by scientific data and evidence-based policy alone — certainly not when science itself is under unprecedented attack in our society; not when environmental laws are in imminent danger of being dismantled; not when the very status of an observed and documented fact is undermined by the brazen contempt for reason and unsettling embrace of doublespeak that now constitutes the discourse of the new administration.

In such fraught and perilous times, a sustainable future can only be achieved, let alone properly envisioned, with the full participation and engagement of the environmental arts and humanities.

By showing us the “second nature” of the urban landscape in these images of green rooftops, Brad Temkin’s art not only delights and inspires with unexpected manifestations of beauty, but also implicitly challenges us to consider what “first nature” is, and what sort of relationship we want with it — one which in we are conquerors . . . or stewards.

This is a slightly edited version of a short speech I gave at the opening reception for Rooftop: Second Nature on 9 Feb 2017 at Roosevelt University’s Gage Gallery, 18 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago IL. The Gallery is open 9am-5pm weekdays and 10am-4pm Saturdays.

All I Want for the Holidays is a MAP Grant

To the Roosevelt University Community: please help pressure our Illinois legislators to fund MAP grants for our students!

To the Roosevelt University Community: please help pressure our Illinois legislators to fund MAP grants for our students!

On Wednesday, Dec. 14, from 11:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. during the Winter Brunch, please stop by and sign the “All I Want for the Holidays is a MAP Grant” banner. Take a selfie and post to social media with #MAPMatters. We will share images of this signed banner with our state representatives and senators.

Thank you for your advocacy efforts!

For more information, contact Jennifer Tani, Assistant Vice President, Community Engagement (jtani@roosevelt.edu).