Nature within the urban landscape is simultaneously close at hand and hidden from view — a paradox of proximal obscurity. Yet its myriad forms are as diverse in kind as their human denizens. City parks, urban farms, back yards, forest preserves, vacant lots, and green rooftops — all these and more comprise the spaces of urban nature.

Despite the ubiquity and diversity of urban nature, it remains largely invisible to and thus unappreciated by many city dwellers. We are much more likely to assume nature exists “out there,” away from our cities and suburbs — especially in remote places characterized by few people and sublime landforms. An implicit corollary to that is that the city is unnatural.

Yet the recent coinage of the seemingly oxymoronic phrase urban wilderness signals that we have begun to re-envision the role of nature within metropolitan landscapes. This nature is almost always hybrid in character, a product of human design and action even when appearing “natural” in outward form. Consider our location right here, along the southwestern rim of Lake Michigan — where the surveyor’s grid was laid down upon the marshy prairie, a river’s current audaciously reversed, and lakefront parkland perched atop thousands of tons of landfill.

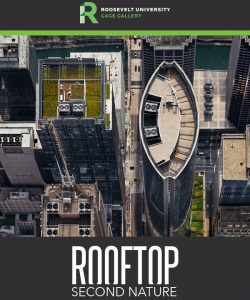

The intersections of the made and the natural can be apprehended in such settings . . . if one observes carefully, knows where to look, and possesses a spirit of exploration. The dramatic roofscapes by Brad Temkin in Rooftop: Second Nature are striking visual compositions that reveal the city from a different and unfamiliar angle, as well as information-rich object lessons in how green infrastructure enhances urban sustainability.

The intersections of the made and the natural can be apprehended in such settings . . . if one observes carefully, knows where to look, and possesses a spirit of exploration. The dramatic roofscapes by Brad Temkin in Rooftop: Second Nature are striking visual compositions that reveal the city from a different and unfamiliar angle, as well as information-rich object lessons in how green infrastructure enhances urban sustainability.

More broadly, though, this exhibit speaks to the vital role played by the environmental arts and humanities in envisioning a more sustainable future for humanity as well as for the millions of fellow species on our beautiful yet vulnerable planet. Thought-provoking ideas, artwork, architecture, poetry, stories, historical accounts, theater, music, and film are necessary complements to painstaking ecological analysis and pragmatic environmental policy.

Why? Because ideas and vision matter. Compelling narratives, whether literary or visual, can animate science, challenge our use of technology, inspire policy, and change hearts and minds. Such narratives must guide our thinking to ensure that social equity and environmental justice are not trampled in the relentless pursuit of short-term profits from, say, building oil pipelines across sources of drinking water in the Great Plains; or dumping the “overburden” of mountaintops into the creeks and rivers of Appalachian coal country; or selling more Pepsi or iPhones.

Skeptics of climate change cannot be persuaded by scientific data and evidence-based policy alone — certainly not when science itself is under unprecedented attack in our society; not when environmental laws are in imminent danger of being dismantled; not when the very status of an observed and documented fact is undermined by the brazen contempt for reason and unsettling embrace of doublespeak that now constitutes the discourse of the new administration.

In such fraught and perilous times, a sustainable future can only be achieved, let alone properly envisioned, with the full participation and engagement of the environmental arts and humanities.

By showing us the “second nature” of the urban landscape in these images of green rooftops, Brad Temkin’s art not only delights and inspires with unexpected manifestations of beauty, but also implicitly challenges us to consider what “first nature” is, and what sort of relationship we want with it — one which in we are conquerors . . . or stewards.

This is a slightly edited version of a short speech I gave at the opening reception for Rooftop: Second Nature on 9 Feb 2017 at Roosevelt University’s Gage Gallery, 18 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago IL. The Gallery is open 9am-5pm weekdays and 10am-4pm Saturdays.