The Leading Edge of Social Justice

A Look Back at Roosevelt Historyby Lynn Y. Weiner, Professor of History Emerita

During a student demonstration on “D-Day,” blondes were barred from the library to highlight the absurdity of racial discrimination.

Seventy-five years ago, Roosevelt University was created as an act of courage when President Edward Sparling, faculty, staff and students walked out of the Central YMCA College of Chicago to protest restrictive admissions policies based on race, nationality and religion.

Roosevelt led the way in American higher education, not only by its early commitment to equal opportunity, but also by the pioneering diversity of its community. Roosevelt University was one of the first fully integrated colleges in the United States, one of the first with an integrated faculty and Board of Trustees, and one of the first to promote social justice and human rights as core missions.

Student Lily Sachs Rose, a refugee from Nazi Germany, was there in 1945 when students walked out to support the new college. She remembered being “totally caught up in the idea of what was possible in this country. To have this experiment in education — it didn’t matter what color you were, your religion, the shape of your eyes. I can’t imagine anything else in my life that was so exciting, so large.”

After 75 years, Roosevelt continues to honor the courage of the founders with a deepened commitment to educational opportunity, academic excellence and social justice.

Over 5,000 students — a fourth of them veterans — poured into the newly acquired Auditorium Building in the fall of 1947.

An Act of Courage in 1945

The new Roosevelt College opened in September 1945 in a hastily remodeled office building on Wells Street and another building for the music school. Roosevelt founders had two months to prepare for fall classes. They purchased used chairs, desks, lab equipment, books and blackboards. Students, faculty and staff pushed carts piled high with supplies through Chicago streets and worked alongside carpenters, electricians and painters. There was no endowment, but donors, big and small, provided the initial funding for the college. Marshall Field III supplied the first payroll.

The college constitution mandated representation on the Board of Trustees from labor, capital, management, cooperatives, the press and faculty. Board membership was integrated by gender, race and religion. Founding trustees included the chair, Edwin Embree, a friend of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and leader of the Rosenwald Foundation. Pioneering African American chemist Percy Julian was named vice-chair and became one of the first black trustees of a majority-white college.

On November 15, 1945, Eleanor Roosevelt dedicated the new college “to the enlightenment of the human spirit through the constant search for truth, and to the growth of the human spirit through knowledge, understanding and good will.”

The new college faculty and staff was one of the most diverse in the United States. Edwin Turner, director of physical education and athletics, coached every sport at Roosevelt and was the nation’s first black coach at an integrated school. President Sparling worked with the American Friends Service Committee to relocate Japanese Americans from wartime internment camps, and many came to study at Roosevelt. His administrative assistant Mary Sonoda, who had been in a California internment camp, said that Roosevelt was exciting “because everyone believed in the principle on which the school was founded.”

EARLY FACULTY

Sociologist Rose Hum Lee, the first Asian to chair a sociology department

Political scientist Tarini Prasad Sinha

Modern dancer Sybil Shearer

Education professor Frances Horwich, who as “Miss Frances” created one of the first children’s TV shows, Ding Dong School

Economist Abba Lerner

Dalai Brenes, chair of modern languages

Sociologist St. Clair Drake

Linguist Lorenzo Turner

Chemist Edward Chandler, the second African American to earn a PhD in chemistry

Eleanor Roosevelt attended Roosevelt University’s 10th anniversary dinner with trustee Percy Julian (left) and President Sparling (right).

Even more diverse than the faculty, students were described by one reporter as “Chinese, Japanese, Negroes, Levantines, Jews, Catholics and Down East Yankees.” Over 1,200 students from 40 states and 15 countries crowded into classrooms on September 24, 1945. Dozens of national reporters visited this “model of democracy in education.”

Within a year, to accommodate rapidly growing numbers of students, Roosevelt purchased the Auditorium Building on Michigan Avenue. Over 5,000 students — about a fourth of them veterans — registered for classes in the new building in the fall of 1947. “We want to open still wider the door of educational opportunity to thousands of young people of all races and creeds and from all walks of life,” President Sparling said.

“We want to open still wider the door of educational opportunity to thousands of young people of all races and creeds and from all walks of life.”

— Edward Sparling

First President of Roosevelt University

Labor education class, 1940s

The Little Red Schoolhouse

Roosevelt’s curriculum reflected its mission of inclusion. A labor education division offered noncredit courses to over 10,000 union members during the first decade. Classes were offered at night for working students. Faculty enthusiastically organized interdisciplinary “informal education” institutes focused on such topics as race relations and public health. Arts and Sciences students were required to take a year of international language or culture study of a non-English-speaking country.

Faculty and students examined professional and social issues through multiple and often conflicting perspectives. The first faculty established a conservative caucus and a liberal caucus, but as economics professor Sara Landau wrote in 1948: “There is assurance that your colleagues who are different also respect you as an individual and as a fellow citizen. Students too differ with each other and with some of us from time to time. But freedom from fear is here, and freedom of speech is here, and freedom of assembly is here.”

“Freedom from fear is here, and freedom of speech is here, and freedom of assembly is here.”

— Sara Landau

Roosevelt economics professor

The Seditious Activities Committee of the Illinois State Legislature investigated Roosevelt in 1949, and though no evidence was found of subversion, Roosevelt was labeled as “the little red schoolhouse.” In response to the investigation, the New Republic reported that “the only subversive activity at Roosevelt College is democracy — real democracy, the kind you can live, not the kind you just talk.”

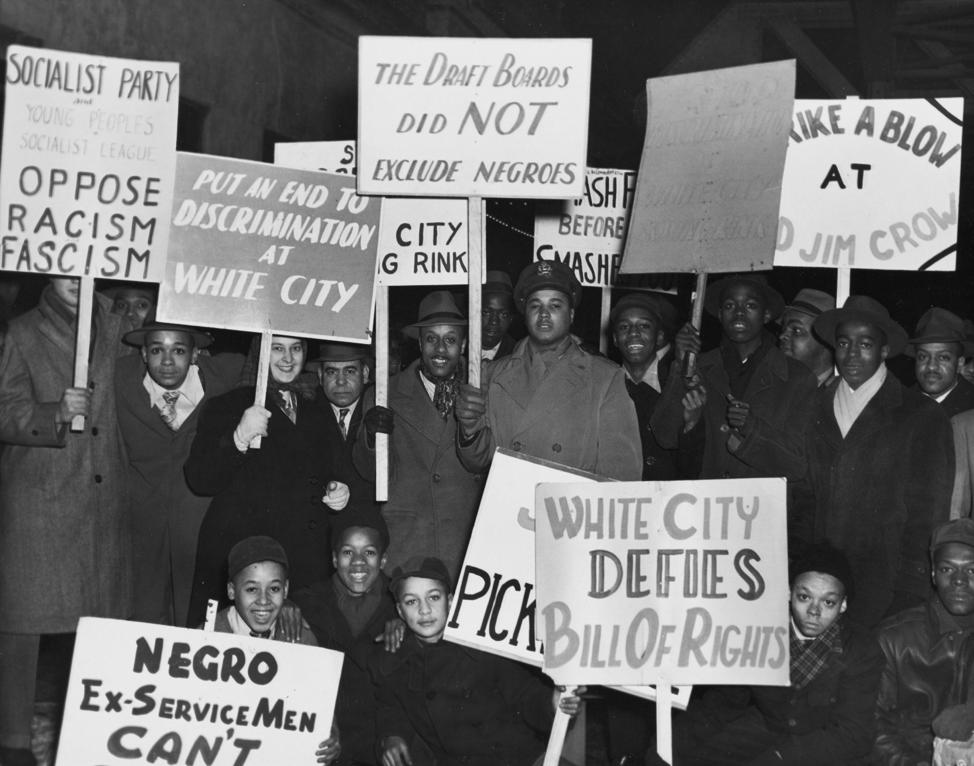

Roosevelt College students joined with protestors at the White City Roller Rink to demonstrate against racial discrimination in 1949. Credit: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-019601.

Training Ground for Activists

In 1948, Roosevelt students, including future Chicago Mayor Harold Washington, helped form Beta Sigma Tau, the nations’ first interracial and multi-religious fraternity. A student Social Action Training Group picketed against racial discrimination at White City Roller Rink, restaurants and retail stores. Students voted to bar the American Red Cross from campus in protest of the policy of segregating blood by race, and with faculty organized a campaign against restrictive real estate covenants in Chicago.

During the 1950s, students organized a public awareness event to highlight the absurdity of racial discrimination. On “D-Day” (Discrimination Day), students barred access to the library, elevators and other locations to blondes, short women and men with mustaches. In 1957, Roosevelt presented civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. with a Founders and Friends Award for his service to the “principles of American democracy.”

In the 1960s and early 1970s, students protested the military draft and Vietnam War and demonstrated for a black studies program. The Chicago Women’s Liberation Union held meetings at Roosevelt, and women’s studies classes were offered beginning in the early 1970s. LGBTQ issues first emerged with an article in the Torch in 1972 on gay militancy, and panels from the AIDS memorial quilt were displayed at Roosevelt in 1987.

A Global Education

The curriculum continued to reflect issues of social justice. Study abroad courses included travel to Tanzania to examine links between food and poverty, travel to Guatemala to study social diversity, and travel to London to learn about comparative criminal justice.

Lakers on a study-abroad trip to Tanzania.

Faculty developed new majors in social justice studies, sustainability studies, and women’s and gender studies. Continuing the legacy of “informal education,” centers and institutes brought outstanding speakers to campus. These include the Mansfield Institute for Social Justice and Transformation, Center for New Deal Studies, the Montesquieu Forum, the Joseph Loundy Human Rights Project, and the St. Clair Drake Center for African and African American Studies, which in the 1990s partnered with Chicago public housing to mentor students.

The Gage Gallery was founded in 2001 to exhibit documentary photography with social justice themes.

And Justice For All

Today the Roosevelt community continues its engagement with social justice. In 2016, President Ali Malekzadeh initiated an annual conference on the American Dream. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg sold out the Auditorium Theatre in 2017 as the keynote speaker.

Students speak out in support of Monetary Assistance Program (MAP) grants, which make it possible for many Illinois students to attend universities.

Student organizations advocate for environmental justice, reproductive rights, voting rights, state funding for education, LGBTQ+ rights and income equality. There are also groups supporting Latinx, African American and international students, among others.

The Center for Arts Leadership in the Chicago College of Performing Arts hosts a social justice residency, and the Women’s Leadership Council, founded in 2019, is dedicated to the empowerment of women as leaders in business and public life.

Student activism continues. Students recently demonstrated for state educational funding grants. Journalism students traveled to Flint, Michigan to report on the water crisis. Education major Jazmine-Marie Cruz organized the 2019 Women’s March in Chicago, and later became the first recipient of the Illinois Human Rights Commission Millennial Activism Award.

The Future of Inclusive Education

In 2019, Roosevelt initiated a collaboration with Robert Morris University Illinois — an institution committed to inclusive education — with a student housing partnership. In March, with approval from the Higher Learning Commission, Robert Morris became a part of Roosevelt University.

The combination of the two universities builds on historic missions of diversity, access to education, and welcoming first-generation students. The expanded Roosevelt University, now 75 years old, continues its founding legacy of educating engaged and knowledgeable citizens who thrive in a diverse and changing world.

Lynn Y. Weiner is professor of history emerita at Roosevelt University, where she also served as dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and University historian. She is the coauthor of the photo history Roosevelt University (Arcadia Publishing, 2014) and author of “Pioneering Social Justice” in Chicago History magazine (Summer 2019).

More in this section

Standing up for what is right

The Untermyer Award honors Long’s many proclivities: nominees are professors who are prolific in their subject area, are innovative in the classroom and combine their teaching with activism.

Our Ted Talk: Remembering President Emeritus Theodore Gross

Ted Gross was a great leader. A man with transforming ideas, which he enthusiastically shared. He had great expectations for us. Above all, his legacy was defined by hope.

The City and The American Dream

Cities have served as key sites of economic innovation and growth, cultural self-expression, and central American ideas, such as the melting pot. This makes the city an ideal lens through which to think about the American dream, especially at Roosevelt University in the heart of Chicago.