Opera’s leading role in transforming gender identity in the arts

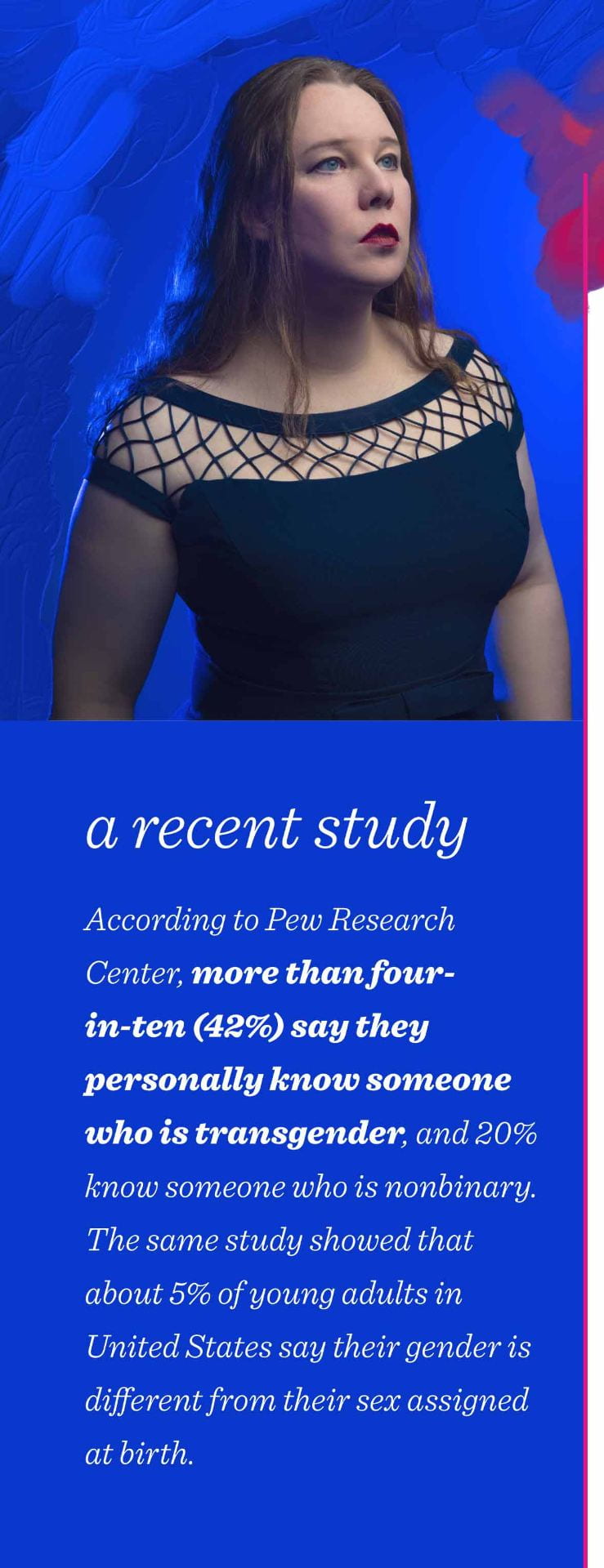

Lucia Lucas is a force—both on stage and off. Her Heldenbaritone voice is rich, deep, powerful and made to project over the orchestra into the upper reaches of the balcony. In April, the Roosevelt graduate made history during her debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago as the first openly transgender person to perform there in a leading role.

“Someone had to be the first trans person on Lyric’s stage, so my presence is significant, but it will only be truly great when it happens again … and again, until it is no longer unique,” she said recently.

By far, this is not the first or only major career accomplishment for Lucas. In 2019, Lucas became the first transgender opera singer to have a leading role on an American stage with the premiere of Mozart’s Don Giovanni at the Tulsa Opera. While preparing for the role, the documentary The Sound of Identity was shot to capture her groundbreaking performance. Also in 2019, she became the first trans opera singer at the Met in her role as Angelotti in Puccini’s Tosca. In January 2023, Lucas added to her Met repertoire by playing Gretch in Umberto Giordano’s Fedora—also noteworthy because it was the first time in 25 years that the theater has presented the show. In 2022, Lucia and co-author Noam Brusilovsky’s production of Working on the Role, which was based on Lucas’s life, won the War Blind Prize, or Hörspielpreis der Kriegsblinden, the most prestigious award for authors of German-language radio plays. In 2022, she also was featured on GRAMMY.com’s TRANScendent Sounds.

While in Chicago this spring, Lucas took some time to discuss her journey during a day off between Lyric performances. She starred as B in the world premiere of Proximity, a trio of interwoven new works that take a somber look at how climate change, gun violence and the longing for connection in a world awash with technology impacts the individual and society. In each of composer Caroline Shaw and co-librettist Jocelyn Clarke’s Four Portraits, Lucas bears witness to the isolating effects of technology. In “The Phone,” Lucas sings a mournful “Hello. Can you hear me?” as she tries to connect with her partner on the other end of a cell phone. In “The Train,” she searches for community with fellow CTA passengers who are all glued to their phones while trying to keep their footing on an L-train as it stops and starts below the city streets. In “The Car,” Lucas follows the voice of the vehicle’s ethereal-voiced navigation system as it directs her, sometimes comically, toward home. Lastly, in “The Forest,” Lucas seems to connect with her partner on a bench in the woods, but wonders aloud, “Is this a ghost story?”

With a fierce innate drive to succeed, Lucas is intense, detail-oriented and persistent. Once she decides to do something, she’s committed. “I can be focused to a fault,” said Lucas.

Now living in Karlsruhe, Germany with her wife, opera singer Ariana Lucas, Lucas grew up in Sacramento, California. Her father, a civil engineer, and her mother, a retired electrical engineer, gave her educational, brain-based toys as a child, which, she said, continues to give her analytic mind a workout and help her build a systematic approach to tackling new roles. She still enjoys puzzles.

While neither parent sings, they did encourage Lucas to study music. She played a number of instruments throughout school and sang in high-school musicals. While attending college at California State University-Sacramento, she remembers asking the opera director about performing. He offhandedly dismissed her, saying he didn’t have time to listen to an audition. A few weeks later, she approached him again.

“I remember him looking down at his watch, saying, ‘Alright, I have five minutes,’” she recalled. “I went up to his studio and sang half a song. He asked if I had ever studied privately. I hadn’t. He asked if I had any interest in that, and I said maybe. I ended up in his voice studio class and he put me in all of the shows.” She graduated from California State University in 2005 with a double major in French horn and voice performance.

While still in California, Lucas read an article in Opera News about Roosevelt’s faculty. She auditioned and was accepted to Roosevelt’s Chicago College of Performing Arts Master of Music program, and later to its Professional Opera Diploma program.

Collaborative teaching environment

One of the advantages of studying at a small conservatory with a number of noteworthy teachers is its collaborative environment. Lucas studied with David Holloway, Judy Haddon, Mark Crayton, Richard Stilwell, Scott Gilmore (who was instrumental in her move to Germany) and Dana Brown. Three of those teachers—Holloway, Haddon and Stilwell—came to Roosevelt at the peak of their careers and had performed, sometimes together, on the stage of the Met. According to Jared Fritz-McCarty, assistant vice president of advancement, each was recruited to Roosevelt because of their talent and their connections to each other.

Brown, DMA and associate professor of opera and vocal coaching, recalls Lucas as being a forward-thinking student who was interested in fully preparing herself for career success.

“Even while getting her master’s degree, she never doubted her own ability and treated herself as a professional,” Brown said. “The fact that Lucia is willing to talk about her experiences in opera (not simply just coming out as transgender) speaks volumes about the honesty with which she approaches her work. Our work at RU with diverse students begins with how students see themselves and pose questions about the status quo. We strive to give them the confidence to articulate their ideas and passions; we then create projects around those ideas.”

Stilwell, now retired, recalled that Lucas was an exemplary student. “Lucia quickly learned the basics needed for a career in opera; that is, how to sing with a bright, forward technique, using good breath support and control,” he said recently. “I remember that she was industrious, always willing to take on challenges, and contributed often to the musical scene of CCPA. Lucia was a complete joy to teach, so when she started having success after success, I was not at all surprised.”

Holloway, also retired, happened to be director of the Santa Fe Opera Apprentice Program when Lucas was at Roosevelt and introduced her to its program. In summer 2008 and 2009, Lucas was chosen for one of the coveted 38 spots from a very large international pool of applicants. The program acts as a bridge between the conservatory and professional life and, according to Lucas, was very helpful to her career.

After earning a Master of Music in Voice Performance in 2007, for which she received a half scholarship, Lucas went on to earn a Professional Diploma in Opera in 2009. Diploma students receive a full tuition waiver and a stipend during the two-year program, which is underwritten by the Chicago Opera Theater. “I’m very grateful for the help I received from the University and Chicago Opera Theater,” Lucas said. “Full-time students have virtually no time to work outside their busy study and performance schedule, so scholarships can make a tremendous difference to not only the student directly but also, eventually, to the world of opera by training new talent.”

As a professional diploma student, Lucas sang with the Chicago Opera Theater and remembers going to area schools to sing to students as part of community outreach. “Kids would hear our vocal projection and ask, ‘Where’s your microphone?’ It was fun and it was cute, but in the long run, introducing opera to young people one school at a time is not the best way to fill theater seats. It needs to be scaled-up dramatically,” she said.

One way to fill seats and broaden audiences’ world view is to increase diversity in both casting and content, or, as London-based English National Opera Chief Executive Stuart Murphy once remarked, “We want our stage to be as diverse as our city.”

“More representation on stage means more representation in the audience,” Lucas said. “If you put trans people on your stage, you just might see trans people show up in your audience because they want their community to succeed. I think that that goes for any community.”

Fritz-McCarty, who also is a fellow alumnus of Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts, attended the premiere of Proximity and shared that “The diversity represented in Proximity’s cast and audience was simply beautiful; however, it unfortunately is not representative of a typical opera experience. To witness individuals of all identities — of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age and so on — come together in one place showed the desire people have to support works in which they see themselves represented.”

Lucas believes that if young people participate in what makes it to the stage, their desire for relevant content will change the art form. “If opera doesn’t grow and change with the times, people will go elsewhere for their art. You can’t argue with sold tickets.

“It takes people to risk things to move anything forward,” she continued. “My credo is ‘Be who you needed when you were younger.’ I want people who happen to be trans to pursue whatever they want and be able to say to friends and family, ‘I’m trans,’ and have them reply, ‘Great. What are your pronouns?’”

Lucas believes the institution of classical music has a social responsibility to create new works that provide a platform for new voices. “I am happy to promote companies who take a strong stance in embracing diversity. The Lyric Opera Chicago, the Met and the English National Opera are companies that come to mind that further enhance diversity, equity and inclusivity through their actions and policies.”

Pandemic’s Upside

When Covid-19 hit in spring 2020, all businesses, whether a restaurant, a theater or a school, had to find new ways to deliver their goods to the public when customers couldn’t be present. According to Lucas, when the delivery methods changed, so did operas’ content.

“One of the wonderful things about performing new music is we don’t have to worry about how things were done before: it’s a wide-open canvas,” she said.

During the first summer of the pandemic, George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police drew massive public outrage and a general awareness of the inequalities underrepresented communities face. “In so many cases, the way people are treated differently continues to be chilling—and we’re only seeing those cases captured on video,” Lucas said. “Every industry has had to take a look at how they treat people and determine how they can better serve their constituents. By questioning and addressing our biases, not just in policing but in every sector, we can do better for our communities.”

When Lucas came out in 2014, there were no other openly trans people in opera. The general theater director where she was performing at the time was concerned about her voice possibly changing. Lucas had done her homework and knew that transitioning would not affect her voice. “I told him, for better or worse, it won’t change. I have recorded my voice every single month since the year 2000 and have noticed no change.”

People have asked what effect being trans has had on her life, to which Lucas replies: none. “Being trans doesn’t have much to do with my daily life at all. Singing is what impacts my life all the time. It tells me when to eat, when to sleep, where to travel, where to live. Opera rules my life.”

While Lucas has chosen to navigate the complexities of her pioneering role openly so that those who come after her can do so more easily, she believes it’s more important to be known for her operatic career, talent and persona than as a trans opera singer.

“I want to be sure I’m very, very prepared so that there’s lots of positive representation so trans people can keep getting employed and won’t have to give up their passion to live their authentic life. By being extremely prepared, I want to show opera companies, or performing arts companies, that if they only have one experience with a trans performer, it is positive. That’s what drives me.

“I also believe that for any artist, the more open they are about themselves, the better their art is going to be. Many times, the term ‘gender dysphoria’ is used to describe the unease a person feels when their biological sex doesn’t match their gender identity. Conversely, I like to describe my feeling after transitioning as ‘gender euphoria.’ Especially when I first came out, I had this nice calm feeling. The way I feel now reflects an internal energy that comes from feeling good about myself, and when a person feels good about their life, it’s projected on stage. I definitely think that positive energy is really great for performing. So, now when I play masculine characters on stage—which I do for probably 95% of my roles—I’m in character. I’m acting. What’s freeing is that when I’m offstage, I no longer have to act. It allows me to save all my acting energy for the stage.”

Commenting on the political controversy surrounding the rights of the trans community, Lucas wishes people would concern themselves more with their own lives and less with other people’s. “It takes way more energy to hate than to simply ignore,” she said. “And I’d be perfectly happy with people ignoring me. If somebody sees me and hears about my story, they can say they don’t get it and move on. I don’t need them to like me. I don’t need more friends. But for someone to use extra energy to make my life more difficult, I find that a waste of time. Instead of trying to impose your views and ideas and beliefs on me, why not use that energy to make your own life better?”

Engaging with Students

Lucas likes it when companies pair performance pieces that feature people’s identities or community struggles with activism. The before-and-after talks of a performance are a good way to get the conversation going, she said. “It’s clear the Lyric invested time, energy and money into Proximity. With their careful attention to detail, they have done the whole project justice.”

With her engagement at the Lyric, performance majors got to attend a talk before the show on the first Friday in April.

“I hope I gave students and others attending the talk a realistic idea of what’s going on in the business right now, especially in light of the changes that have happened over the last few years,” she said. “I like to give actionable advice to students, things that they can actually do or try. If their goal is to be on stage after they graduate, how do they navigate that when they’re meeting resistance? How might they be able to jumpstart their career if it stalls at some point?”

For instance, when Lucas was a student, she wasn’t cast in an opera one semester, so she found a local group that was producing opera on a tight budget. That group’s conductor is now world-famous, and the two are still in touch. “You never know what’s going to happen when you put some energy towards something,” she said. “As a student, you meet classmates, and it can be really wonderful to see where their careers go. You may not grow in parallel; sometimes it might feel like people disappear from the business and then reappear, and then suddenly you’re crossing paths again. You really never know where those relationships are going to take you.

“We would love to think that our career path is a very long planned-out arc, but sometimes the right communication just happens at the right moment,” she continued. “Those connections are everything. Maybe you discover that you used to go to school together and they ask you to audition, or they may ask you for a recent recording. At the same time, there are gigs where I didn’t even know until after the show was over how I was chosen. Once, during an audition, I learned that a director had remembered me from a rehearsal six years earlier. You may not know for years how your pathways will reconnect.”

One of those connections for Lucas was made with renowned composer Tobias Picker. While serving as artistic director of [the] Tulsa Opera, Picker asked Lucas to audition for the title role in his forthcoming opera Lili Elbe, based on the life of the transgender painter who was among the earliest recipients of gender-affirming surgery (Eddie Redmayne received a Best Actor Oscar nomination in 2015 for portraying Elbe in The Danish Girl). Upon hearing Lucas sing, not only did Picker cast her in Lili Elbe (which premieres in October in St. Gallen, Switzerland), but immediately realized he wanted to engage her sooner as the lead in the Tulsa Opera’s Don Giovani.

With the 2019 premier of Mozart’s classic opera Don Giovani in Tulsa at age 38, Lucas became the first transgender opera singer to have a leading role on an American stage. James Kicklighter’s documentary film The Sound of Identity features Lucas and Picker talking about the groundbreaking production in which Lucas starred as the master of disguise—one of the opera canon’s best-known protagonists.

Two Operas at Once

So how does a singer rehearse for one opera while performing in another? Before and during her Proximity run, Lucas continued collaborating as a singer and as a dramaturge with Picker on Lili Elbe by recording the scores for him and returning them; she sings, he adjusts. After working together on its score over the past 10 months, Lucas said the opera is almost complete. “In my experience, this type of collaboration and time commitment is fairly common for a world premiere,” she said. “In comparison, I did work on another world premier that had lots of last-minute changes, but I don’t think Lili Elbe will be that way. Proximity, for instance, was very, very organized from the beginning.”

Similar to her onstage Don Giovani character, Lucas doesn’t mind the public not recognizing her off stage. “If people do not look down at their program booklet to see my name and headshot, they might not realize who I am in street clothes,” she said.

For instance, last January in her role as Gretch in Umberto Giordano’s Fedora at the Met, she played an old Russian soldier with lambchop sideburns and a mustache. After the performance, most stage door fans didn’t recognize or acknowledge her. “It doesn’t really bother me. I think it’s reasonable for people not to notice me off stage.”

There are the moments, however, when she does get the spotlight. “But I don’t need that all the time. My career is going well,” she said.

She credits some of her grounding to performing on major stages throughout Europe since 2009. “As an artist living in Germany, singing opera is considered a normal profession—we’re part of the economy. And producing art is seen as a valid job, which is humbling.”

But Lucas still gets a thrill before stepping out on stage, especially when making a debut at a world premiere. To keep herself in check, especially if her adrenaline level is too high, she practices alternate nostril breathing to equalize her energy. “If I’m too excited, I can drop my heart rate 20 beats per minute in just a couple of seconds, and it also gives me better breath control,” she said.

Reflecting on her career, from the time she spent studying at Roosevelt to where she is now making history on the world’s stages, Lucas said simply, “I still think it’s pretty cool that I get to sing for a living.” ●

More in this section

President’s Perspective – Spring 2021

There is no getting around the fact that we are currently a deeply divided nation. But this is hardly the first time America has been divided.

Psychology Alum Helps Black Women Reclaim Joy

Melisa Alaba considers herself a breakthrough coach. As the founder of Vision Works Counseling and Coaching, she leads a team of therapists — all Black women — who coach women of color through emotional issues.

What Historical Pandemics Teach Us About COVID-19

Bygone plagues call to mind ghastly historical dramas and Monty Python skits, ostensibly far removed from the sanitized comforts of modernity. However, the COVID-19 pandemic actually bears a striking resemblance to many historical plagues.