Inside Out

Harold Washington’s Stamp on Chicago EducationA Conversation with Dr. Al Bennett

Six months into Mayor Washington’s second term, Chicago was simmering with frustration over education. The teacher strike dragged on for a record-breaking 19 days. Parents and union members marched in the streets to demand teacher raises, smaller class sizes, more resources.

Washington decided to hold an education summit that would explore ways to improve Chicago Public Schools. He invited over 500 parents, educators and local leaders to discuss solutions as equals.

At first, attendees doubted anything would come from the conversation. A month later, Washington’s untimely death would tragically cut short his tenure. But the plans for democratic education took root: in 1988, the Chicago School Reform Act established a new way to bring communities inside schools.

As the Harold Washington Professor of Public Policy and professor of education, Dr. Al Bennett has long been a proponent of this inside-out approach. Bennett reflected on the mayor’s legacy of democratic education and populism in honor of his centennial birthday.

What was it like to be in the city when Harold Washington was campaigning for mayor? What were Chicagoans thinking and feeling?

The prevailing notion was that Harold Washington talked to the Black community — the Black community could support a candidate who could win. Chicago was late into this game in terms of having African American mayors. Gary, Indiana had a Black mayor sooner than we did, in 1968.

Traditionally, if you became the Democratic candidate to run for mayor, all the Democratic aldermen would support you. For Harold Washington, that was no longer the case. In his first election, he almost lost to Bernie Epton, who by all accounts was not a qualified candidate. Many of his Democratic colleagues voted for Bernie Epton instead of him. Significant numbers of Black aldermen and local leaders did not support his candidacy.

Think about Harold Washington’s mindset when he almost lost to a Republican in the city of Chicago. You have to believe that at some point, he thought, Why am I doing this to myself? I had a nice Congressional seat. The tenor of the times was that citizens of Chicago couldn’t accept an African American mayor. It was a very small margin of victory the first go-round. I have to believe that he had to keep his eye on the prize.

“The tenor of the times was that citizens of Chicago couldn’t accept an African American mayor. I have to believe that he had to keep his eye on the prize.”

— Dr. Al Bennett

When Washington was elected, the city council bifurcated. These fissures occurred into his first term, when a group of white aldermen blocked every proposal that Washington made. The Vrdolyak group, led by former alderman Ed Vrdolyak, coalesced in total opposition. The Vrdolyak group didn’t allow Washington to move forward until his second election, which ended prematurely

How did Harold Washington’s beliefs influence your praxis and early career?

My first acquaintance with Harold Washington was when I was in graduate school. Bill Berry, the head of the Chicago Urban League, was a well-regarded statesman in the Chicago community. His niece and I were in graduate school at the same time, and so every Saturday, we would meet and I would get glimpses into how Mr. Berry was trying to influence Harold Washington to run for the office of mayor.

We had serious discourse on what it means to be an African American running for mayor in Chicago, the city of neighborhoods, and how difficult and challenging that would be. Bill Berry understood the complexity of it, but believed it was possible. And indeed, it became a reality.

Roosevelt University will establish the Harold L. Washington Hall of Honor in fall 2022. This permanent installation will recognize the lifetime achievements of Mayor Washington and other distinguished members of the University community.

“We hope students will be inspired by the greats who came before them,”

said trustee Patricia Harris.

“My whole work as the Harold Washington professor has been the desire to bring the University out to the community and the community in to the University.”

— Dr. Al Bennett

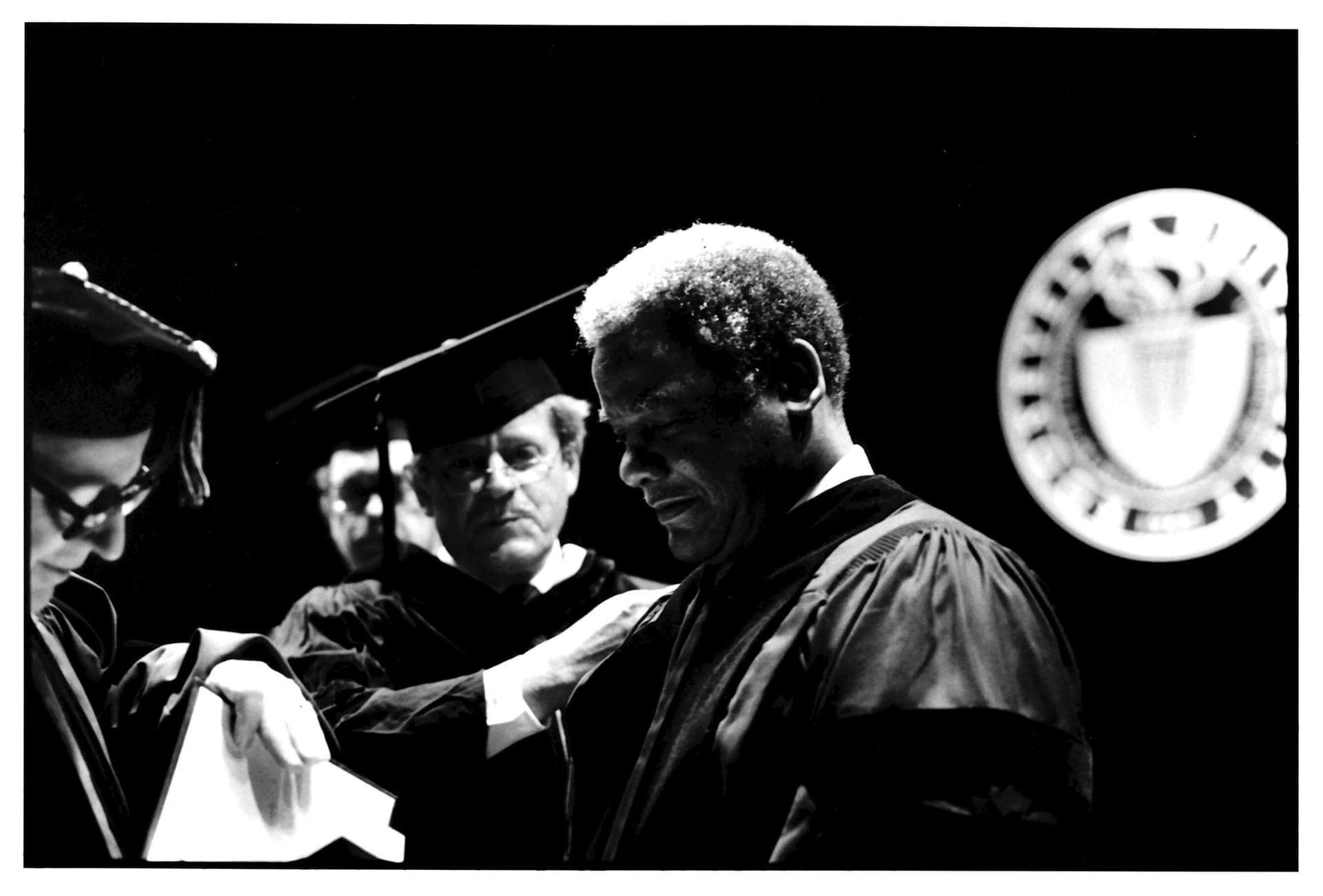

Harold Washington gives the Commencement address at his alma mater, Roosevelt University.

When I was at the Chicago Community Trust, our first initiative was to provide resources for individual local schools to make decisions about what they needed. This was a $5 million initiative, which at that time was quite a bit of money. We were able to implement the philosophy that local schools know what they need.

At the Consortium on Chicago School Research, we did a significant amount of research on principals, teachers and students. We were one of the first groups that came out without equivocation and say local school councils are working.

You also serve as the director of the St. Clair Drake Center for African American Studies, named for a founding Roosevelt professor. What connection do you see between the two men, and in your role?

My whole work as the Harold Washington professor has been the desire to bring the University out to the community and the community in to the University.

Universities are sometimes feared in the broader community because they are so formal and sometimes distrusted. Historically, universities have gone out in the community, gathered information, and published their findings without sharing and sometimes without the sensitivity needed.

Both St. Clair Drake and Harold Washington believed in the inside-outside notion. St. Clair Drake worked with students as well as those in the community who faced critical issues, and Harold Washington worked outside of the normal structures of politics to bring more people in.

My role balances the legacies of both. It’s important that the Drake Center not be considered solely a university operation.

Through the St. Clair Drake Center, you founded the Black Male Leadership Academy. How does the BMLA connect to Washington’s legacy? How would you describe the experience for participants and their families?

The Black Male Leadership Academy has brought Black boys into the Roosevelt University experience. It also connected people outside of the university, building networks that they otherwise would not build.

During the BMLA, we bring Black boys into the wonderful living quarters at Roosevelt and then take them to museums and baseball games. I have a colleague who takes our guys out to the community and talks about the history of its development. We’ll go to Grant Park, for example, and look at the Bean and talk about what happened here. We talk about who’s in, who’s out, and the power and politics of the city of Chicago.

That is democracy in action: putting the boys in spaces where they’re going to be comfortable and flourish. That’s Harold Washington.

Several of the moms weren’t sold on whether or not we would be able to protect their young boys, who had never been away from home before. I tell them that I will take care of your children the way I take care of mine. And I have 20-year-old twin boys — that’s the highest bar.

“That is democracy in action: putting the boys in spaces where they’re going to be comfortable and flourish. That’s Harold Washington.”

— Dr. Al Bennett

What’s especially important is the connectivity between and among black Boys. We know that some of these Black boys are in different gangs — that’s the reality of how Chicago is carved up. But you would be surprised at the level of support, camaraderie and friendships that cross all of that and make it irrelevant.

At the Chicago Community Trust, I learned that when you bring people into your house, you feed them. At the end of each BMLA summer institute session, we hosted a big banquet with the families of all of these young men. We break bread together and create bonds. The young men and their families could have conversations with the university president, something that they couldn’t imagine.

Professor Al Bennett and Marsha Howard (MPA ’95) at the Harold Washington Legacy brunch.

How do you see the legacy of Harold Washington’s achievements today?

For a time, we thought equality was the cornerstone. While that’s still there, we are now pushing issues of equity. How do we give people what they need to succeed when one size doesn’t fit all?

We struggle sometimes, in the broader community, to acknowledge and implement Washington’s vision of what and who we should be. You have to understand that it’s hard for Chicago, which views itself as a city of neighborhoods, to accept the fact that those neighborhoods have historically been a proxy for racism and exclusion.

“You can’t get discouraged, because the alternative is to do nothing, and we can’t do nothing. We have to celebrate our victories, take whatever failures we have, and try again.”

— Dr. Al Bennett

Our work is battling that history, which limits who we are, where we are, and where we go from here. We can’t ignore the fact that while people think fondly of the city neighborhoods, there are neighborhoods where until recently, and probably still, people of color are not welcome.

You can’t get discouraged, because the alternative is to do nothing, and we can’t do nothing. We have to celebrate our victories, take whatever failures we have, and try again.

I see Washington’s legacy every day at Roosevelt University as a social justice school. That’s what makes us who we are — pushing institutions to be more open and more equitable, doing research that supports that.

What we want to do is to push the rock up the hill a little bit more. It’s gradual, continuous work. Roosevelt faculty, staff and leadership continue to believe in just moving it forward.

Dr. Al Bennett is the Harold Washington Professor of Public Policy and professor of education at Roosevelt University. He arrived at Roosevelt as dean of the Evelyn Stone College of Professional Studies, working with adult students.

Previously, he worked for the Chicago Community Trust and Chicago Public Schools as director of program evaluation in the department of research and evaluation. He also served as the co-director of the Consortium on Chicago School Research.