Leaving a Roosevelt Legacy

Donor SpotlightA t Roosevelt University, more than 90% of students receive financial aid as they work toward a college degree. Two new named scholarships will sustain the legacies of Roosevelt trailblazers and support the next generation of students.

LeArthur Dunlap

Determined to make a difference

Before attending Roosevelt University, LeArthur Dunlap (BA Political Science, ’49) was among the first African American sailors allowed to join the Navy after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

At Cape May where he served, African American sailors were required to sleep on the cement floor of the hangar deck, as there were no sleeping facilities for sailors of color, and were not allowed to eat in the mess hall with the White sailors.

Determined to make a difference, Dunlap staged a protest and soon found himself meeting with Naval Captains — arrangements were made for housing, and the African American sailors were allowed to eat in the mess hall. He was honorably discharged from the Navy in January 1946.

After graduating from Roosevelt, Dunlap attempted to find a teaching job, but it was difficult because of intense racism. Dunlap had heard that France was a haven for African Americans escaping racism; in February 1949, he boarded the Queen Elizabeth to start his journey to Cherbourg. With a few dollars in his pocket and his guitar, he found jazz venues to play, with many who became jazz legends.

Dunlap joined the U.S. Army Reserve in 1949 and began working for the State Department. He continued to serve his country until his retirement in December 1983.

Dunlap’s distinguished career included working with several intelligence and international security agencies. He became the Federal Aviation Agency security ambassador to Africa, and regularly traveled to the Ivory Coast, Senegal, Gabon and Benin. He became an expert in terrorism and traveled the world training airport security on how to handle bombs.

Established in remembrance of his accomplishments, the LeArthur Dunlap Scholarship will award $1,000 each year to an African American student with a background in ROTC or who is a veteran.

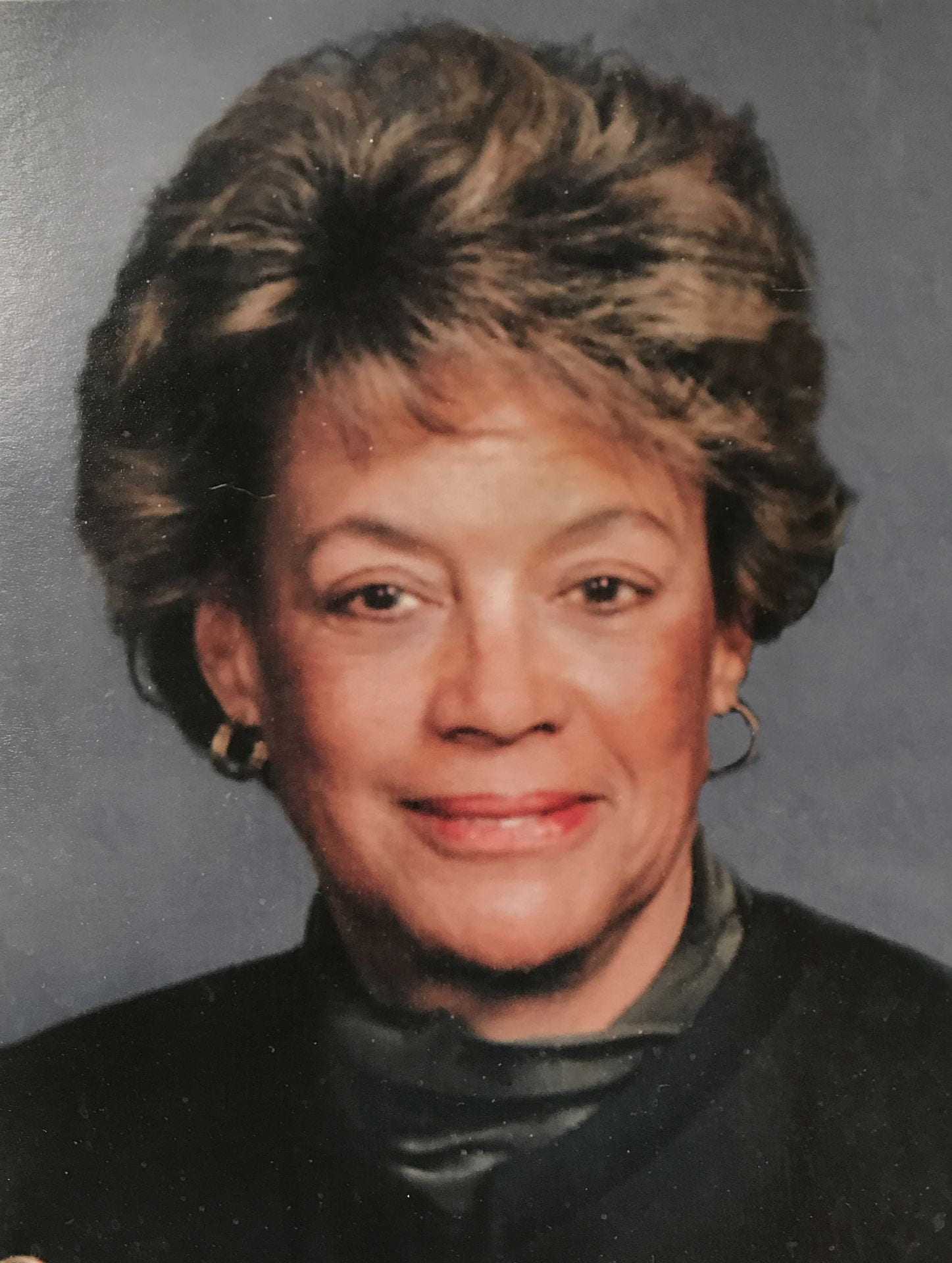

Dr. Juliann Bluitt Foster

“It’s not enough to be the first”

When Dr. Juliann Bluitt Foster became a dentist, there were few women and even fewer African American women in the profession. She told the Tribune in 1988 that she went into dentistry because she wanted “to do something I could believe in, to be independent, to have a challenge and to do something that was different for a woman. I liked science and working with my hands.”

Dr. Bluitt Foster mentored students as a long-time administrator at Northwestern University’s dental school. She was the first woman to be president of the American College of Dentists and the Chicago Dental Society. For 28 years, Dr. Bluitt Foster served on the board of directors for Health Care Service Corporation, the parent company of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois.

Dr. Bluitt Foster often said that “It’s not enough to be the first; it’s just really important not to be the last,” Dr. Theresa Gonzales told the New York Times.

In 1973, she married Roosevelt alum Roscoe Foster (BS Biology, ’52), who practiced orthodontics in the Kenwood Hyde Park neighborhood for 30 years. Like Juliann, Roscoe earned his degree in dentistry from Howard University. He loved languages, particularly Spanish, which he studied throughout life, stamp collecting and classical guitar. He passed away in 2014.

To honor the pair’s achievements and values, the Roscoe C. Foster Jr. and Juliann Bluitt Foster Scholarship will benefit students who are “academically deserving and financially needy.” The scholarship will help sustain the success of students for years to come.

For more information about establishing a named scholarship, contact director of development Jared Fritz-McCarty at jmccarty@roosevelt.edu.

More in this section

In Memoriam | Summer 2023

Roosevelt University extends its deepest sympathy to the loved ones of recently deceased alumni and friends.

Building community one glass floor at a time

Nathaniel Thomas lived his freshman year in the Wabash Building, which he describes as “a big, blue, beautiful skyscraper.”