Forensic Files

Tim Mulholland (MSAF '18)by Katy Cesarotti

Who protects adults when they can no longer protect themselves?

As a Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE), Roosevelt alumnus Tim Mulholland (MSAF ’18) took on a pro bono case and delved into court records to investigate alleged elder abuse in the Oakland County Probate Court.

Driven to prevent what he calls “injustices that were done to defenseless people,” Mulholland dedicated hundreds of hours of volunteer labor to evaluate possible evidence of fraud committed by court-appointed guardians.

He contributed his findings to a series of articles by investigative reporter Gretchen Rachel Hammond, published the same day that the Michigan attorney fired three of the four professional guardians identified in Hammond’s reporting.

A social-justice education

“Forensic accountants inhabit a cloak-and-dagger corner of the accounting world,” wrote one Associated Press reporter. “Their job: respond at a moment’s notice when a client spots trouble.”

Certified fraud examiners like Mulholland resolve allegations from employee theft to embezzlement to money laundering, the crime made literal in Skylar White’s car wash in Breaking Bad. These financial experts have to sift through mountains of reporting documents and records in what Mulholland describes as a “very involved, unbiased and precise process.”

Tim Mulholland (MSAF ’18)

Tim Mulholland (MSAF ’18)

“Forensic accountants inhabit a cloak-and-dagger corner of the accounting world. Their job: respond at a moment’s notice when a client spots trouble.”

— Associated Press

Forensic accounting is Mulholland’s second career. On a field trip to the Chicago Board of Trade as an undergraduate, he fell in love both with the city and the exchange floor. He relocated to Chicago and worked his way up as a futures commission merchant and global financial market executive, interviewed frequently as an expert by news outlets like CNBC, Bloomberg News, Fox Business, Sky Business, BFM FM Kuala Lumpur and WGN News.

When he considered returning to school, Mulholland focused on accounting programs that would prepare him for the CPA exam; he only later became interested in forensic accounting. His decision came down to the University of Illinois and Roosevelt, and he chose Roosevelt for the close interactions between his cohort and faculty.

“The mood was very kind, and there were a lot of smiling faces,” Mulholland said of the University. “It was a community environment that I was proud to be a part of.”

Roosevelt is home to one of the few forensic accounting programs in Chicago, and he predicts that in the digital era the profession will only continue to grow. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that employment in the field will increase by 7% between 2018 and 2028, faster than the national average.

Then 60 years old, Mulholland was the oldest graduate student in the program. He believes that his experience helped him make the most of his time at Roosevelt. “Having worked many years, it helped to know why things mattered and why it’s important,” he said.

“Tim was one of the highly self-motivated, goal-oriented, and engaging students in our Graduate MSAF program, who was indeed inspiring to a number of his fellow students,” said Asghar Sabbaghi, the former dean of the Heller College of Business. “He was always excited about learning, particularly service-learning activities that would positively impact our community.”

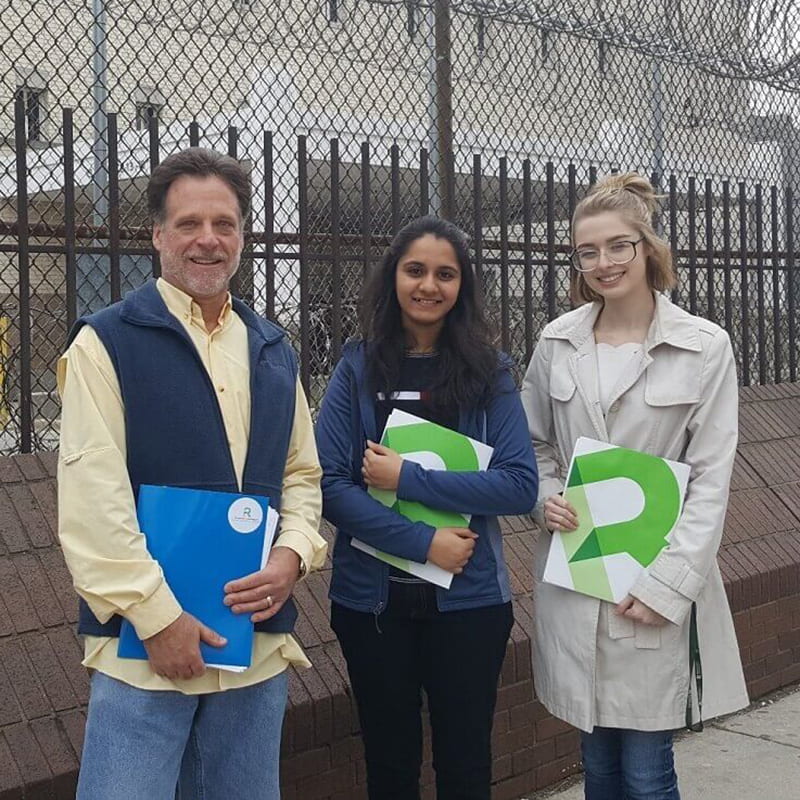

From the left: Timothy Mulholland, Sonali Patel, and Nicolette Marasa

While Mulholland was completing his master’s degree, Sabbaghi launched a financial literacy program in partnership with the Cook County Jail. Mulholland volunteered to lead workshops, where he worked closely with incarcerated people from the Mental Health Transition Center Program and the Thrive Program.

The capstone project helped Mulholland support the greater Chicago community through his education. “The dean said, ‘you have no idea how good you’re going to feel,’” recalled Mulholland. “It was a really rewarding experience to hopefully make a difference.” He cites Sabbaghi as one of his most positive and encouraging mentors.

Taking the first step

After graduation, Mulholland received his CFE designation and was eager to launch his forensic accounting career. He took Sabbaghi’s advice to heart: “Don’t worry about what’s going to happen. Take the first step and engage.” When a mutual acquaintance introduced him to Hammond, who was seeking a forensic investigator for her article, Mulholland volunteered.

Probate courts are intended to safeguard vulnerable citizens from exploitation. If a judge rules that senior citizens or adults with developmental disabilities cannot manage their day-to-day needs, the court will declare them an “incapacitated ward” and select someone to manage their care, appointing a public administrator if no family members can serve in this role.

Guardians manage the medical and residential needs of wards, determining where they live, coordinating their Medicare and Medicaid benefits, and controlling their visitation rights. In fewer cases, when a probate court judge decides a ward needs a professional to manage their estate, conservators are appointed to handle their finances. According to the Michigan State Court Administrative Office, as of December 31, 2018 there were 60,712 adults under guardianship in the state.

While legal guardians are appointed to protect the rights of their wards, they also have the power to erode them. Under guardianship or conservatorship, wards surrender access to their homes, bank accounts, credit cards and forms of identification like driver’s licenses or passports. They can no longer decide where they live or how they receive care.

Mulholland began working with Hammond in March 2019; five months later, he had dedicated at least 200 hours of pro bono work. “It was a case that nobody wanted to do — a lot of work and no pay,” Mulholland said. “I drew inspiration from Gretchen, who dedicated one and a half years to the case.”

Mulholland found that the records often lacked invoices and detailed billing. Even attorneys are not allowed to charge their legal hourly rate for their work as guardians, Mulholland found that line items were commingled, meaning that wards were paying as much as $100 an hour for guardians to handle their medical needs. In several cases, family members weren’t notified before cases went to court, or the judges overrode existing power of attorney and living wills.

Mulholland’s 30-page analysis recommended a formal audit of the Oakland County Probate Court process and four professional guardians, calling for greater transparency and additional subpoenaed records.

“It felt good to implement what I learned at Roosevelt,” Mulholland said.

While he worked largely on his own, he drew on the mentorship of Roosevelt professors Husam Abu Khadra and Donald Todd.

“Tim showed high professionalism and dedication in whatever he was doing,” said Abu Khadra, associate professor of accounting. “His interest in using his MSAF degree to benefit the public was always evident and supported by his recent work in the Oakland County pro bono case.”

Mulholland’s work helped him land his first paid client, an experience he hopes will help him launch his own practice in turn.

Now the lifelong learner is considering preparing for a CPA. He’s interested in serving as an outsourced chief financial officer, developing accounting systems for companies, and sharpening his due diligence skills to work on mergers and acquisitions and personal investments.

Mulholland’s advice to future graduates comes from Sabbaghi. “Get engaged,” he says. “Once you engage, then things start taking shape and start happening.”