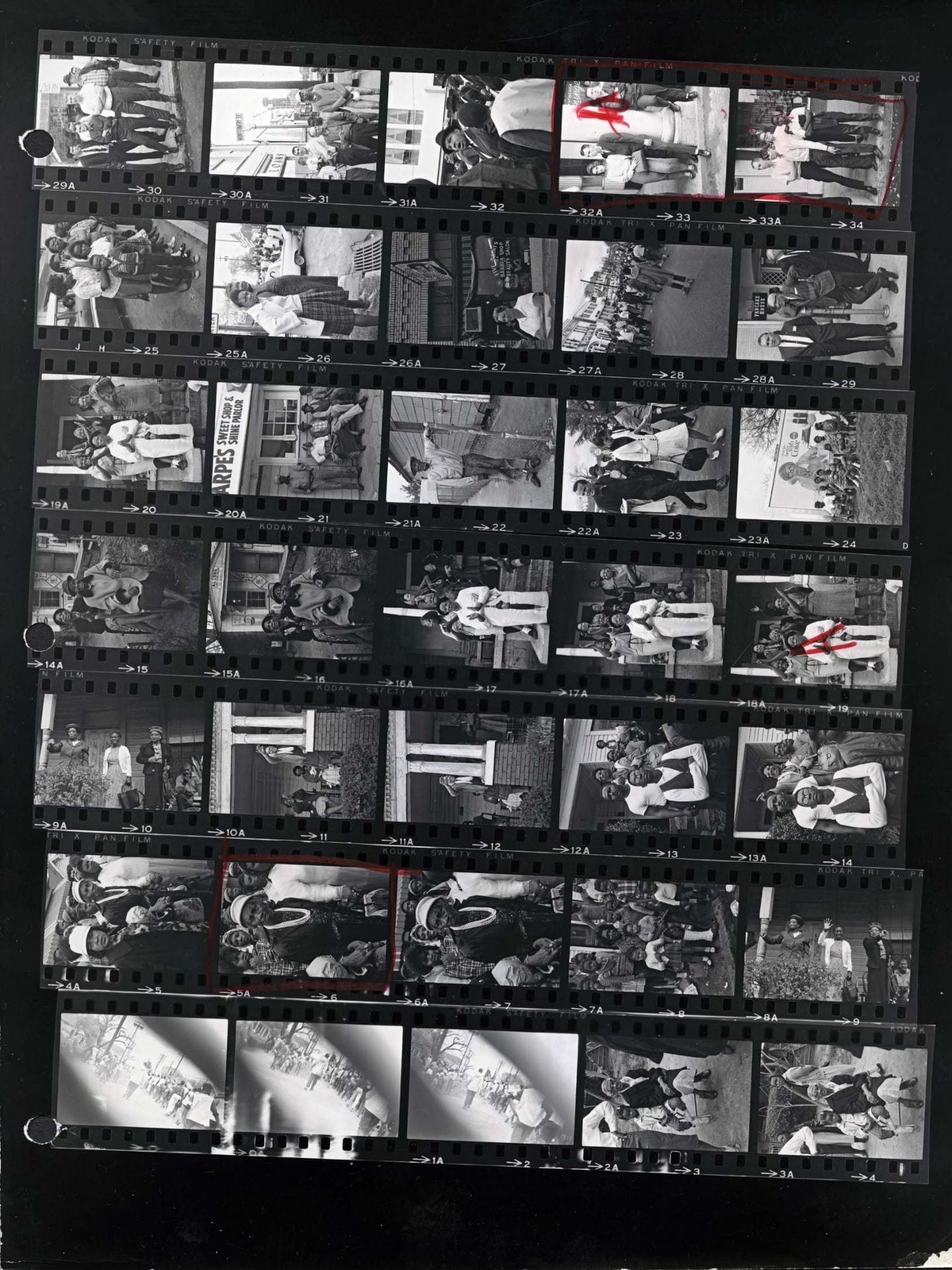

Steve Schapiro:

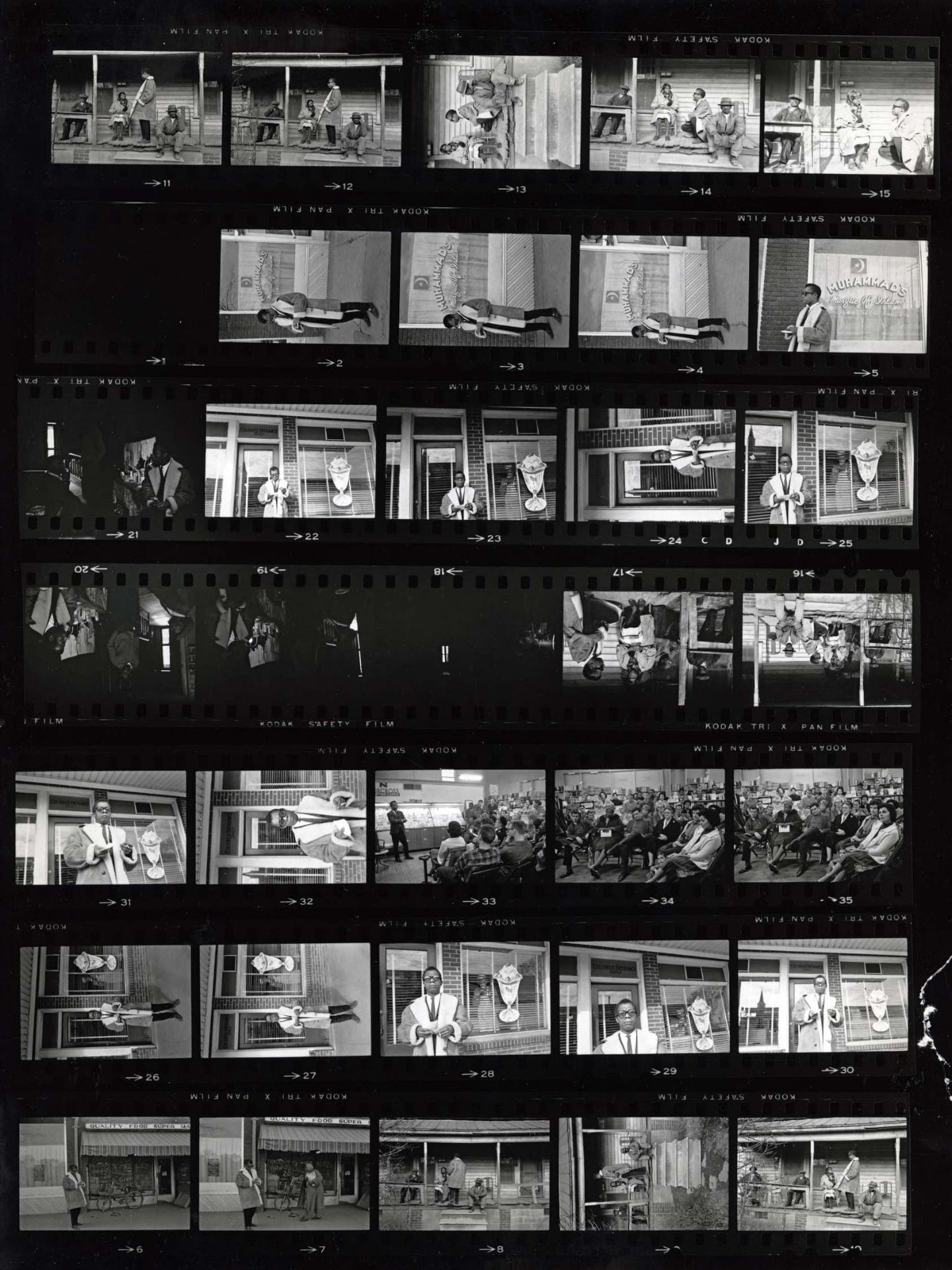

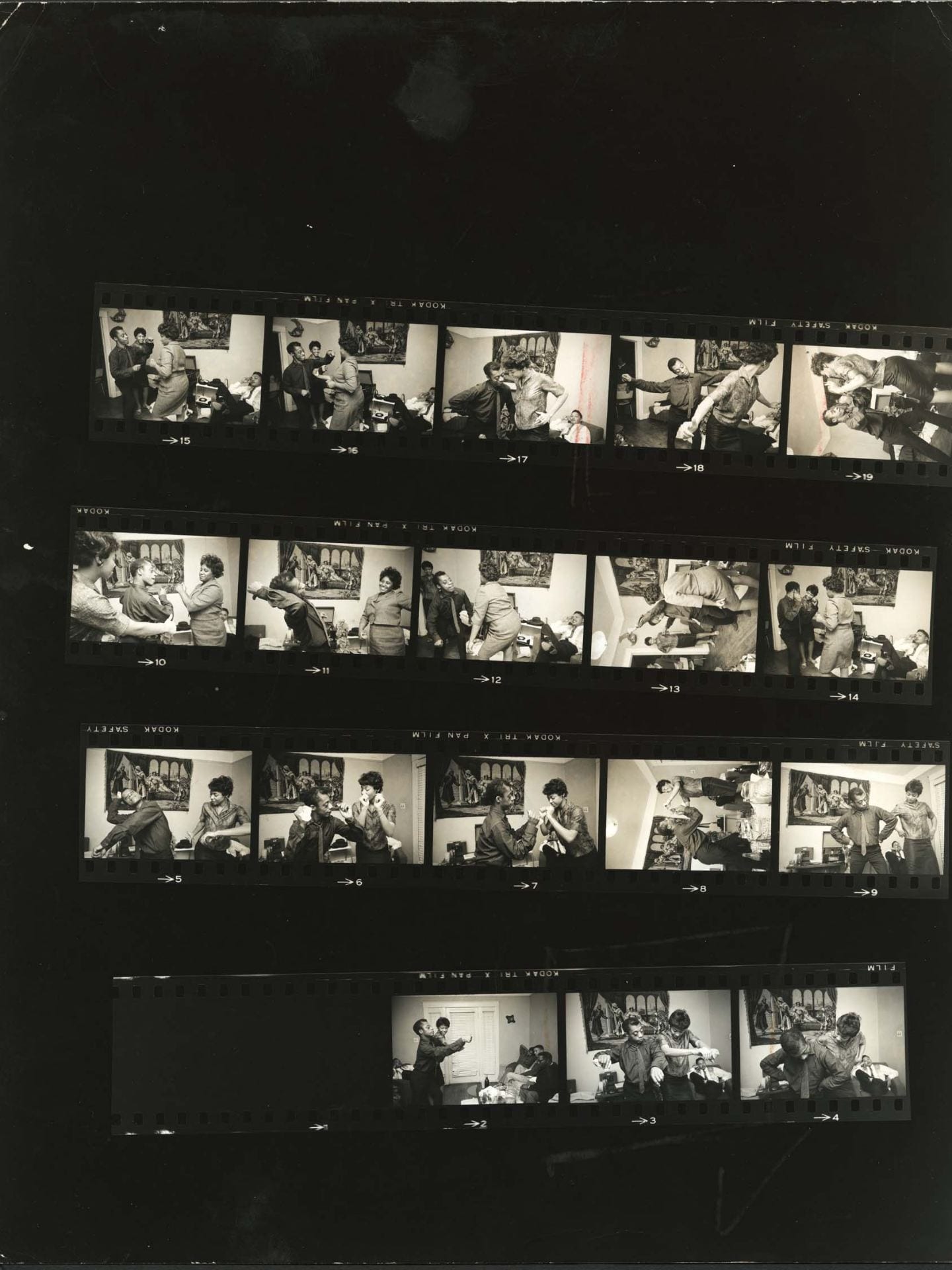

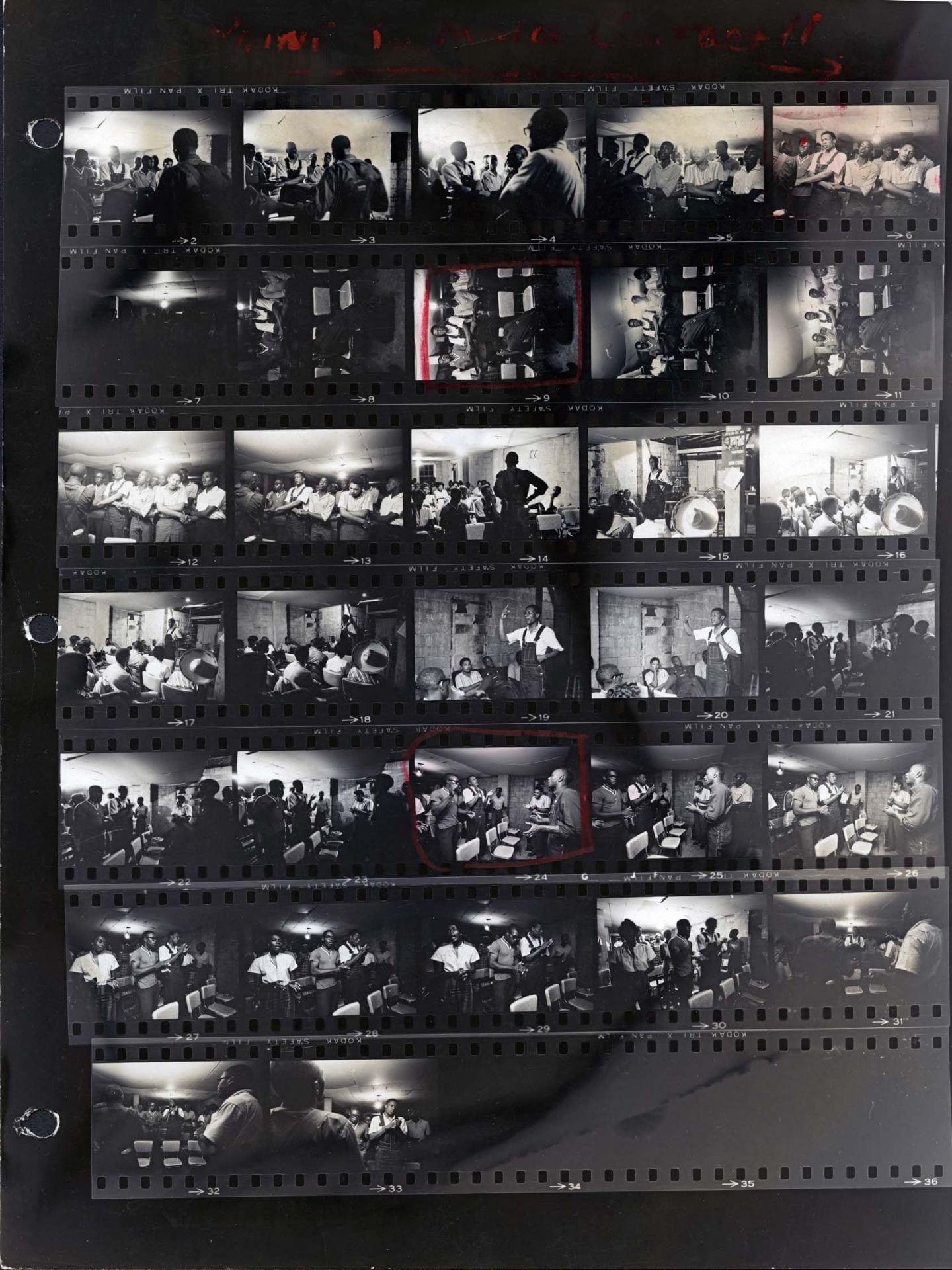

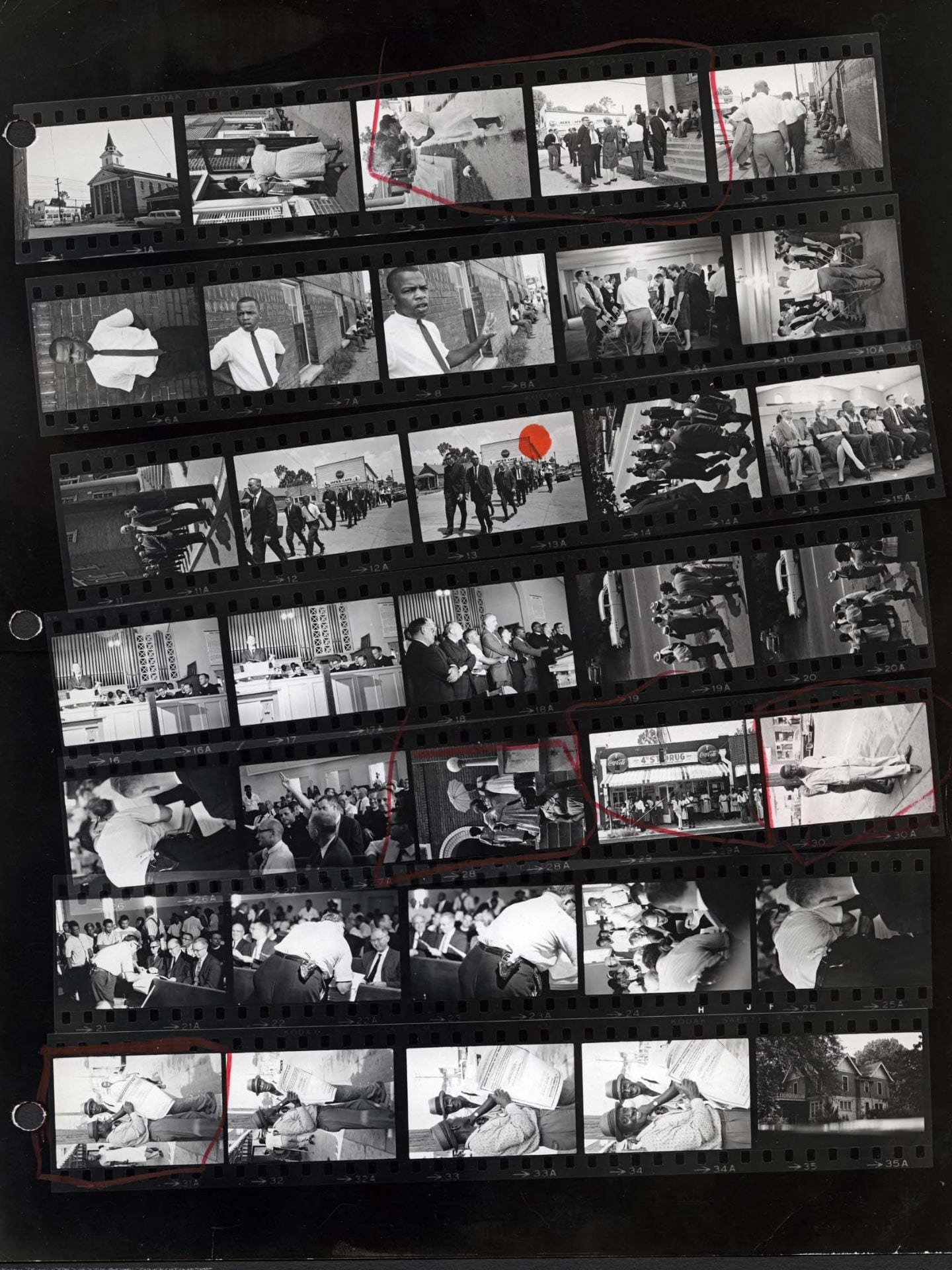

Civil Rights Era Contact Sheets

Gage Gallery Exhibition

by Erik S. Gellman

Associate Professor of History, UNC, Chapel Hill

Curated by Mike Ensdorf, Professor of Photography | Roosevelt University

Text and research by Erik S. Gellman, Associate Professor of History | University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Sponsored by Roosevelt University’s College of Arts and Sciences, with generous financial support from Susan B. Rubnitz and Elyse Koren-Camarra

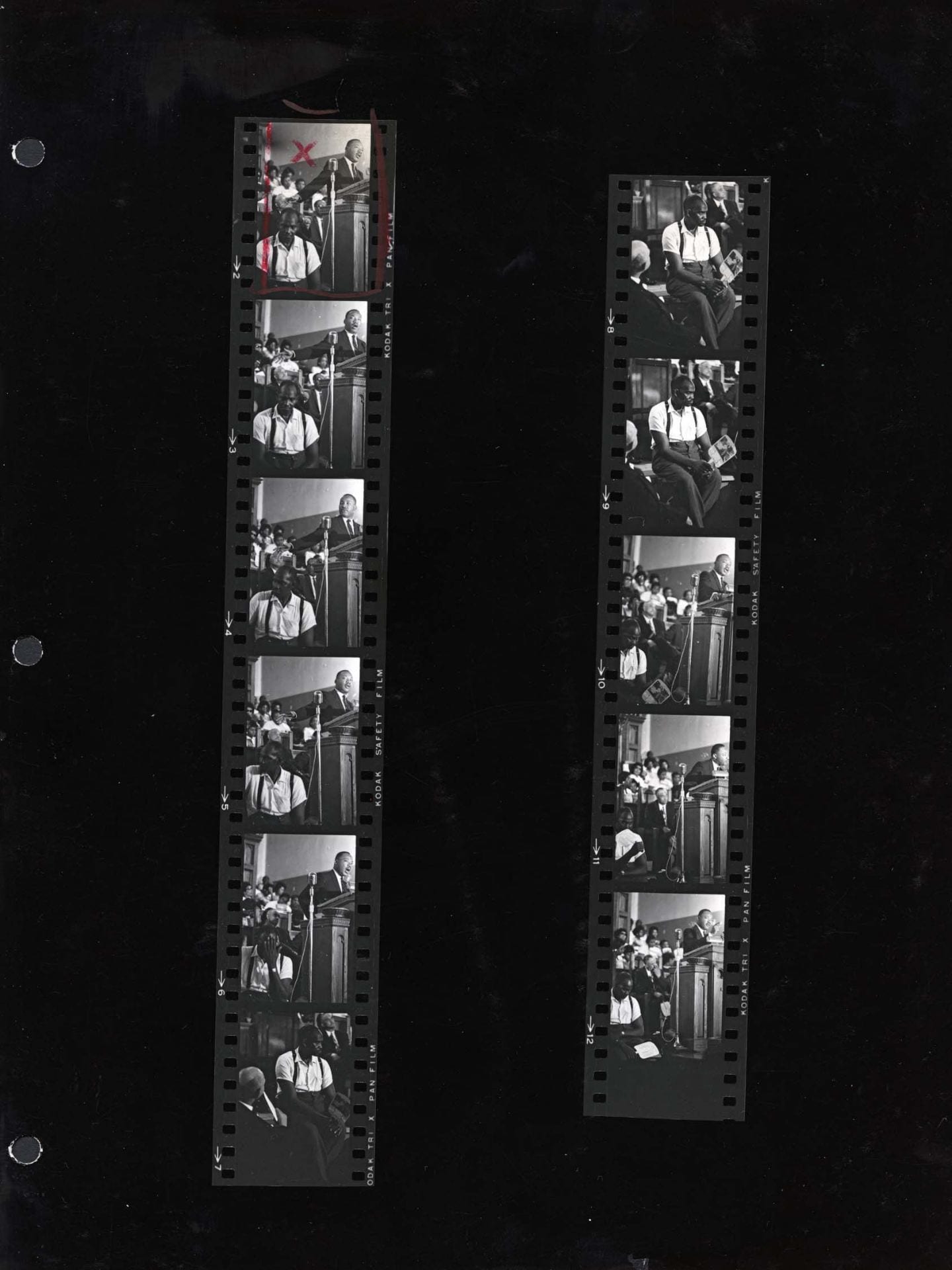

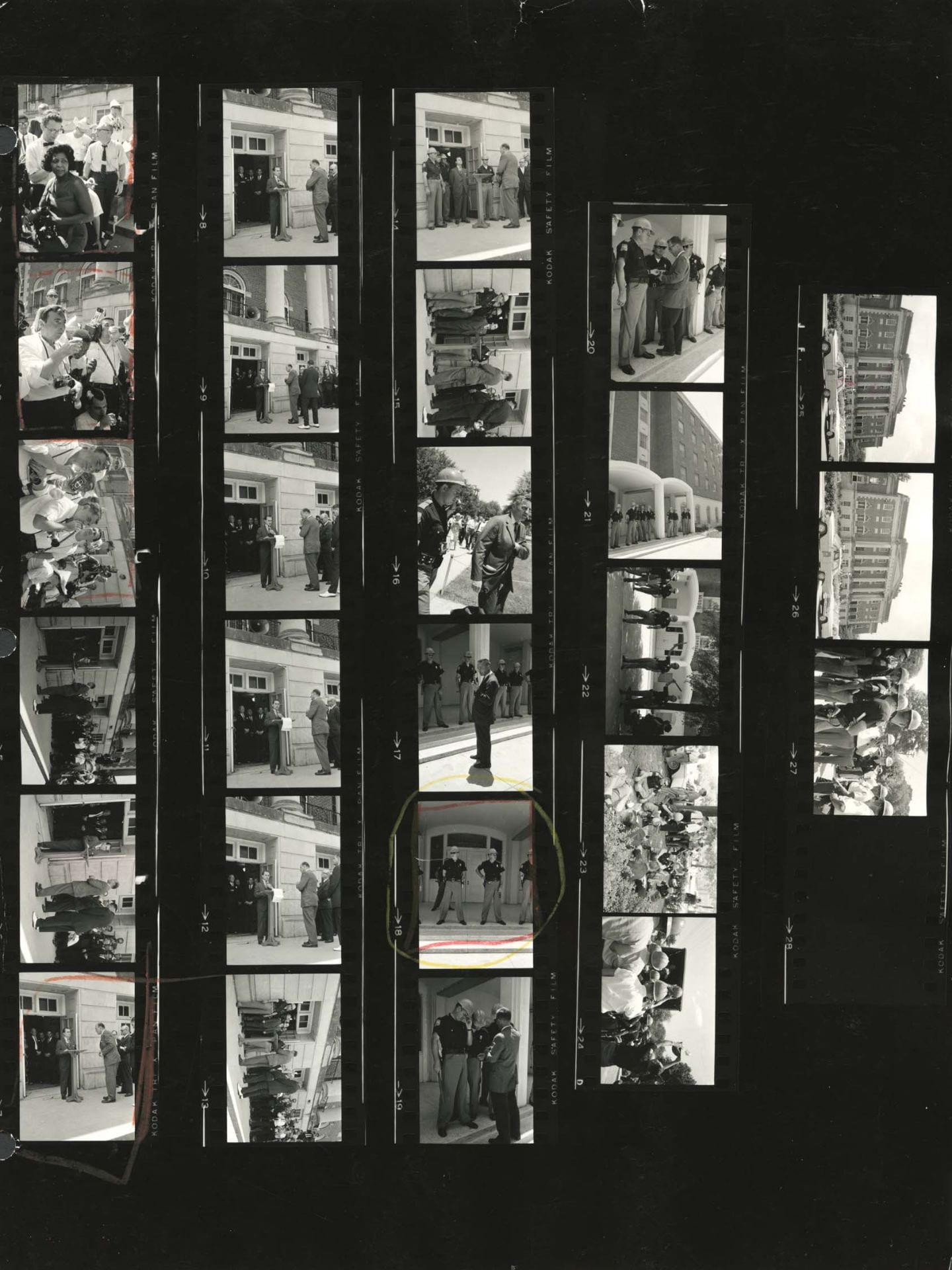

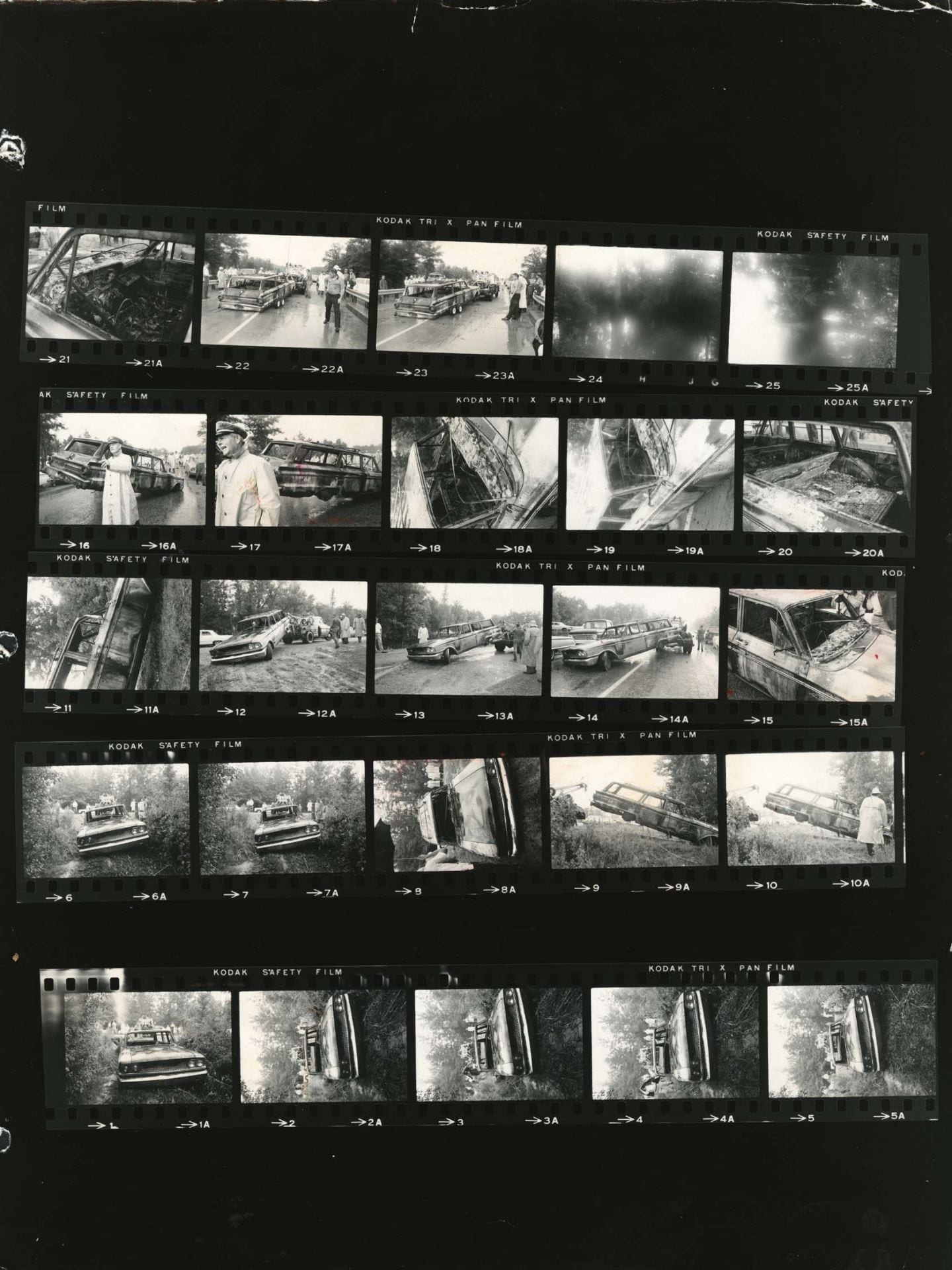

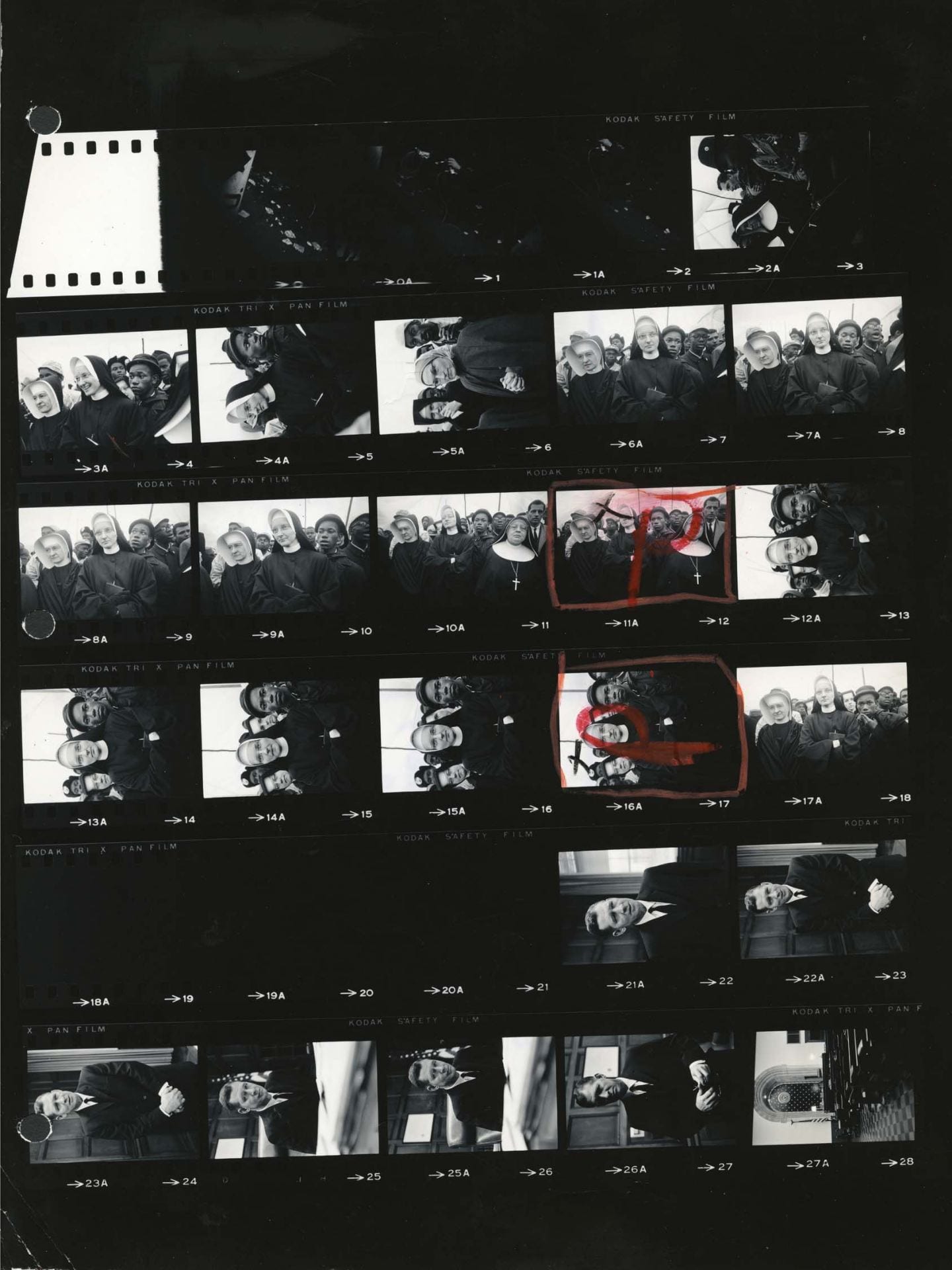

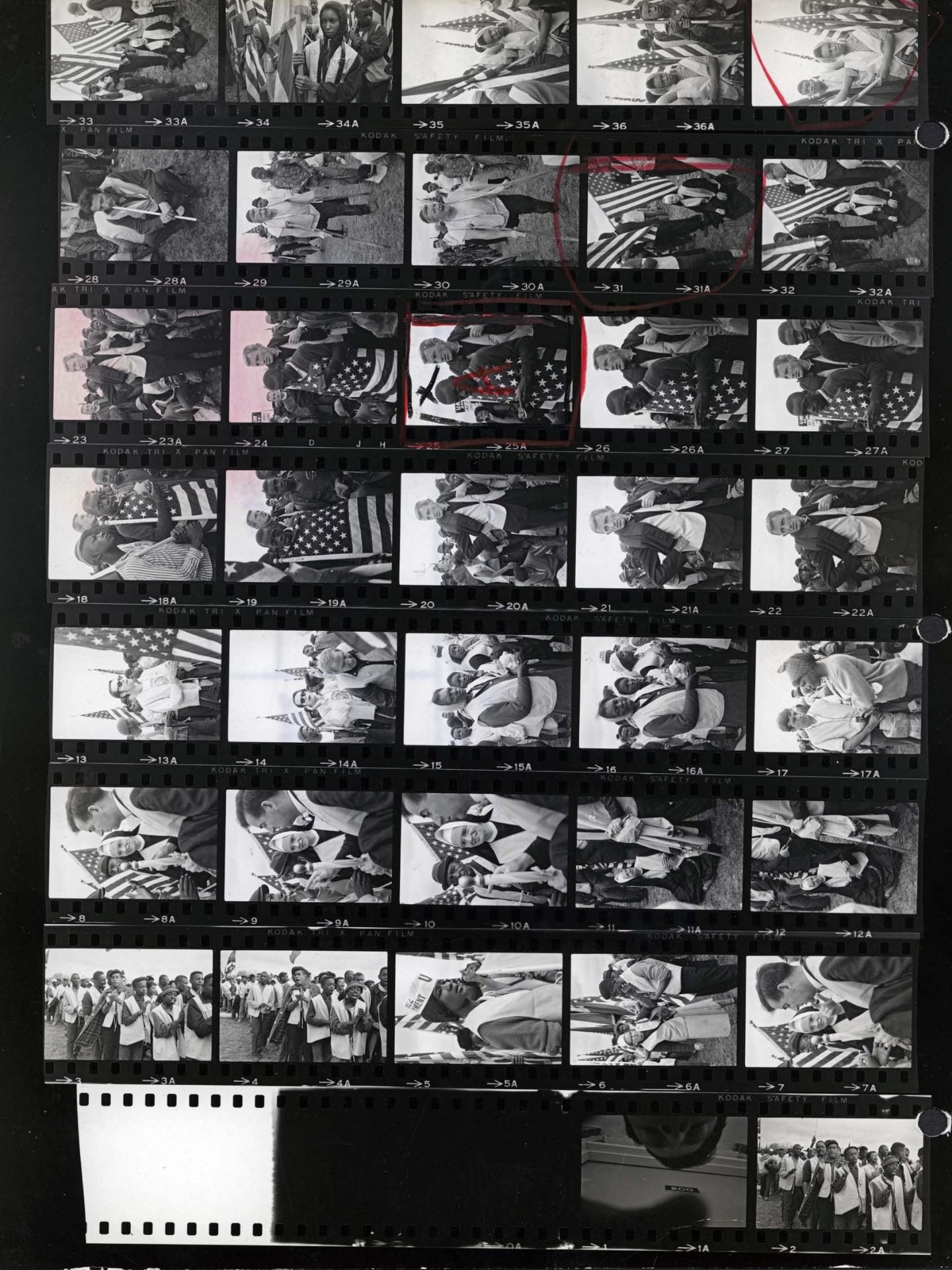

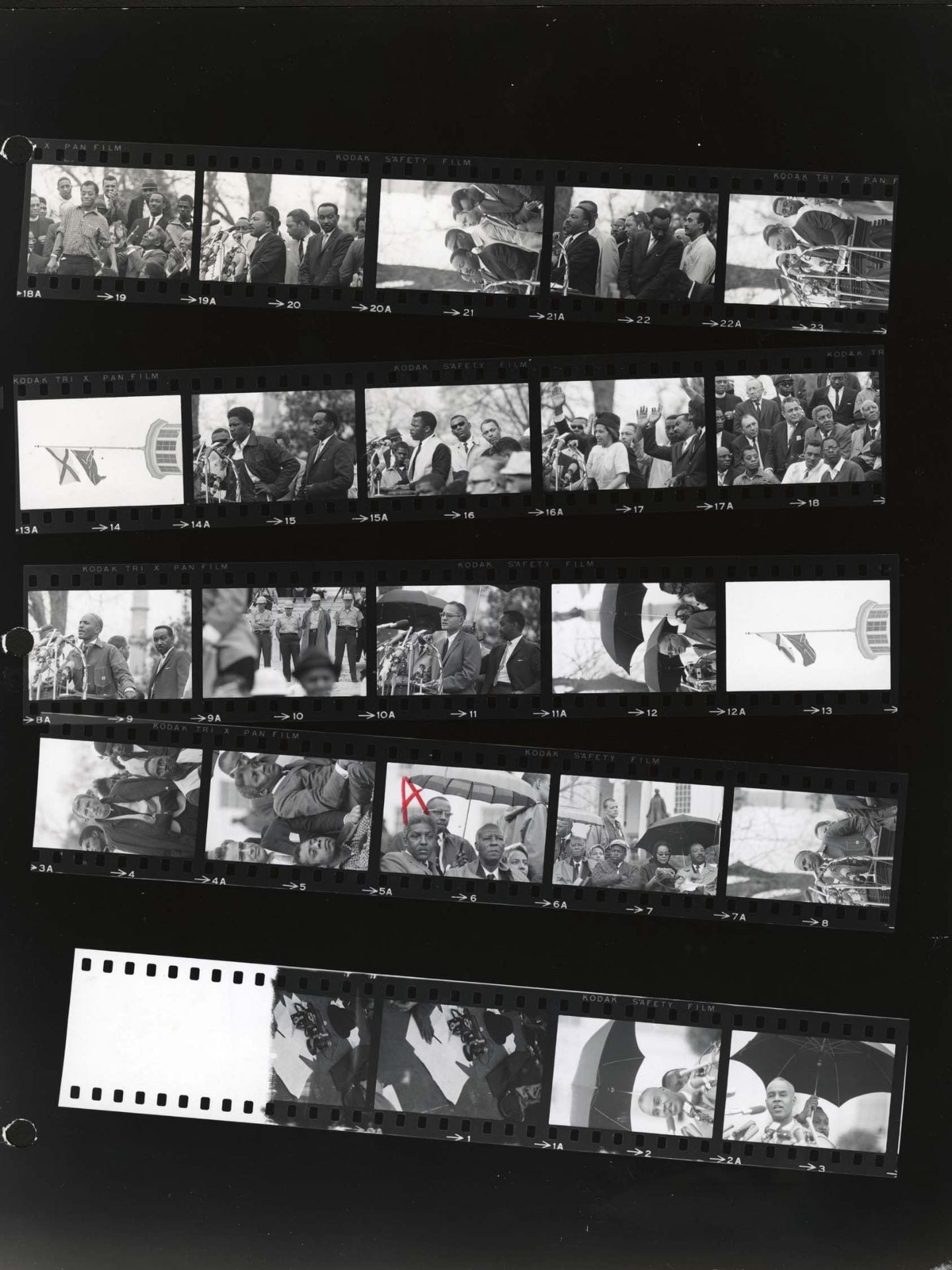

In the “golden age of journalistic photography,” Steve Schapiro took pivotal and now-famous photographs of the southern civil rights movement.

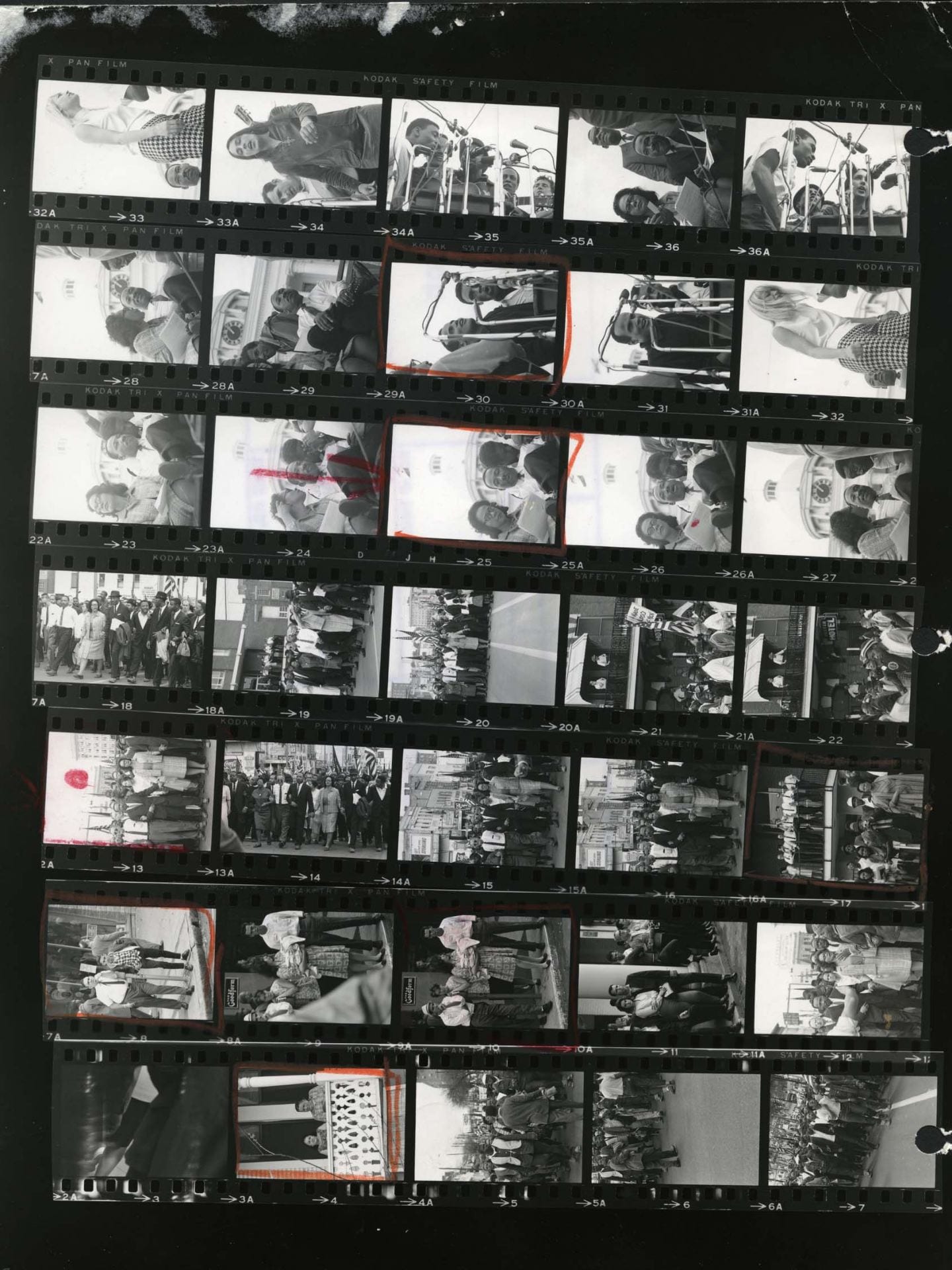

Americans in the mid-1960s were devouring photo-driven magazines, with Life Magazine reaching more than 32 million readers each week. This provided ample opportunities for Schapiro and other photographers to earn a living and reputation. With their published images reaching a vast audience, these photographers had a journalistic and artistic platform to document and promote the pivotal 1960s struggle for justice.

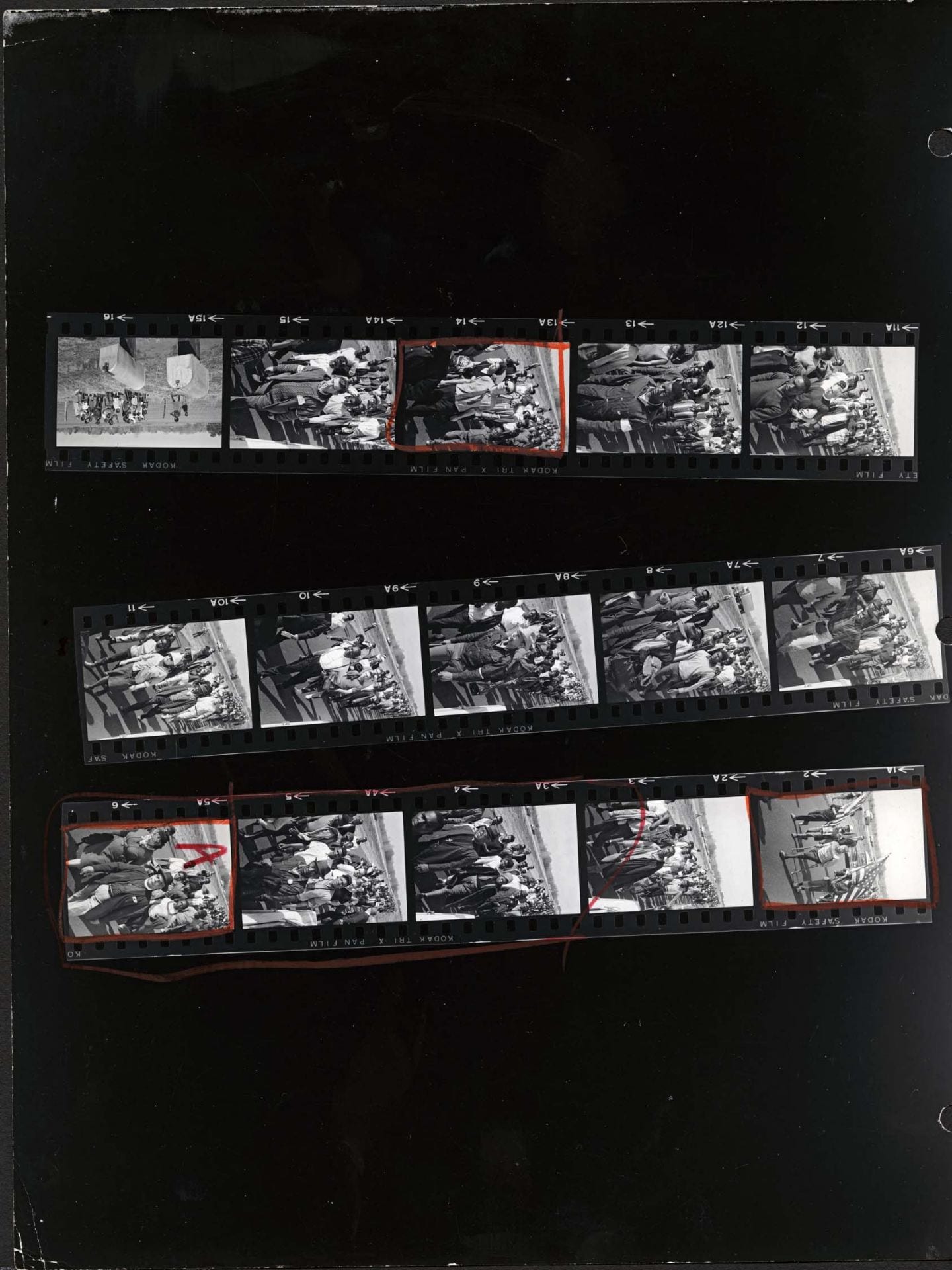

But this outpouring of mid-20th century photojournalism met some challenges. Schapiro’s frequent assignments required extensive travel. He lacked the time and darkroom access he needed in order to produce and evaluate his own images. Instead, he mailed undeveloped rolls of film in an overnight envelope to the New York offices of Time-Life or another publication, where a magazine editor would produce contact sheets. These editors, not photographers, ultimately determined what got published. They often selected one “hero frame” from a contact sheet. Such photographs were good illustrations for the accompanying story, but they also put compositional and other artistic factors on the back burner.

(from left): Mike Ensdorf, professor of photography; President Ali Malekzadeh; Steve Schapiro; and Bonnie Gunzenhauser, dean, College of Arts and Sciences

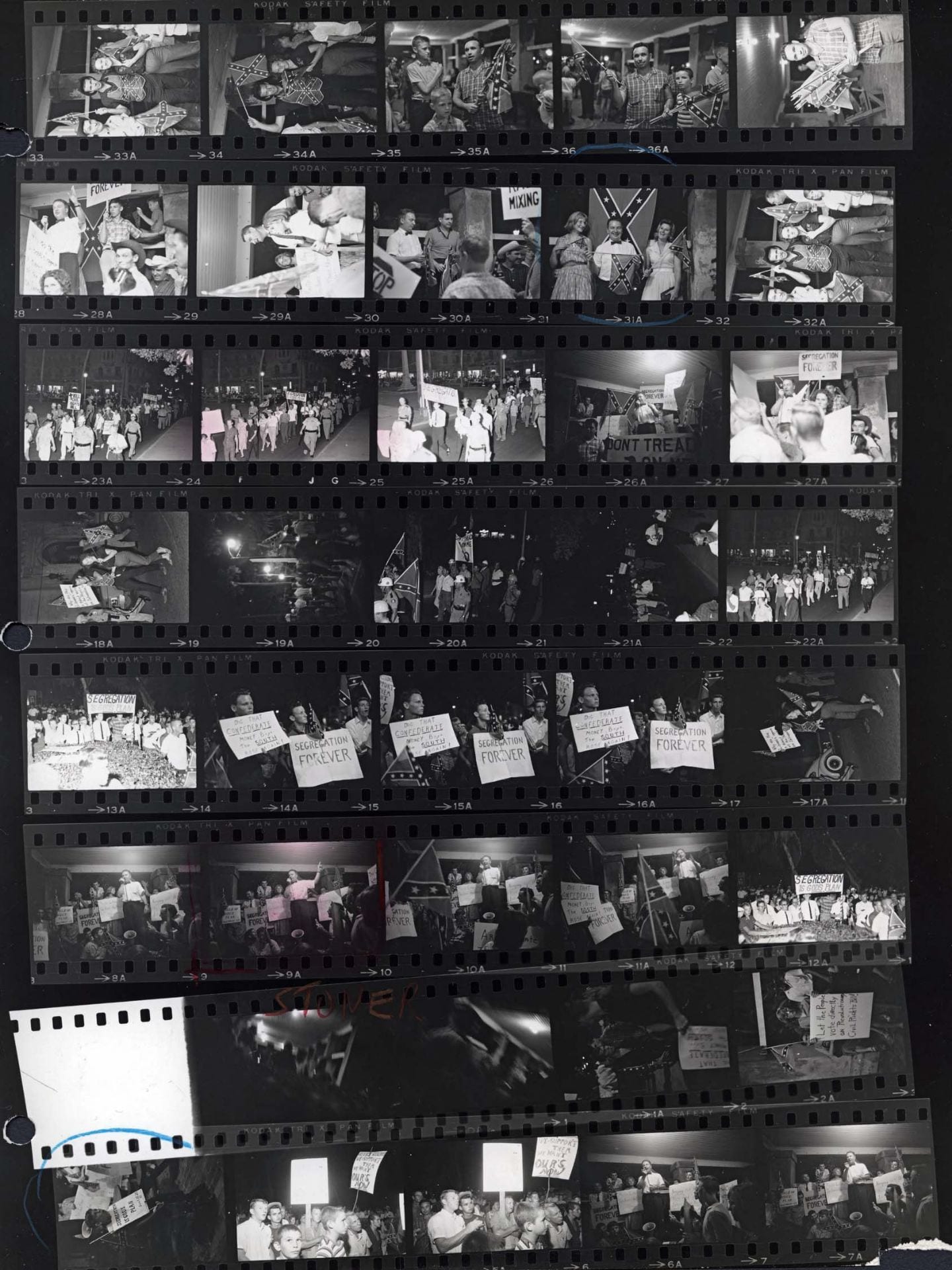

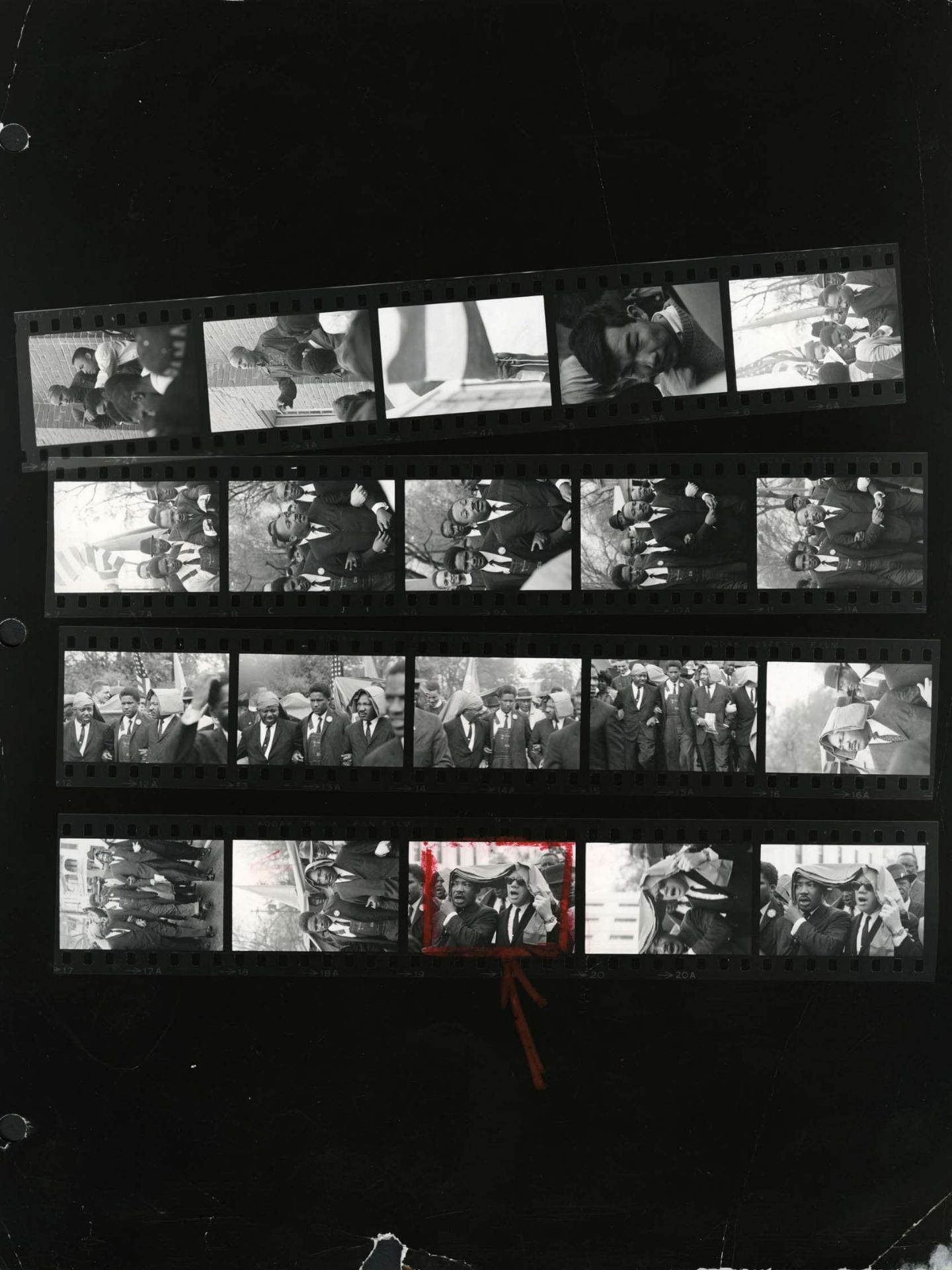

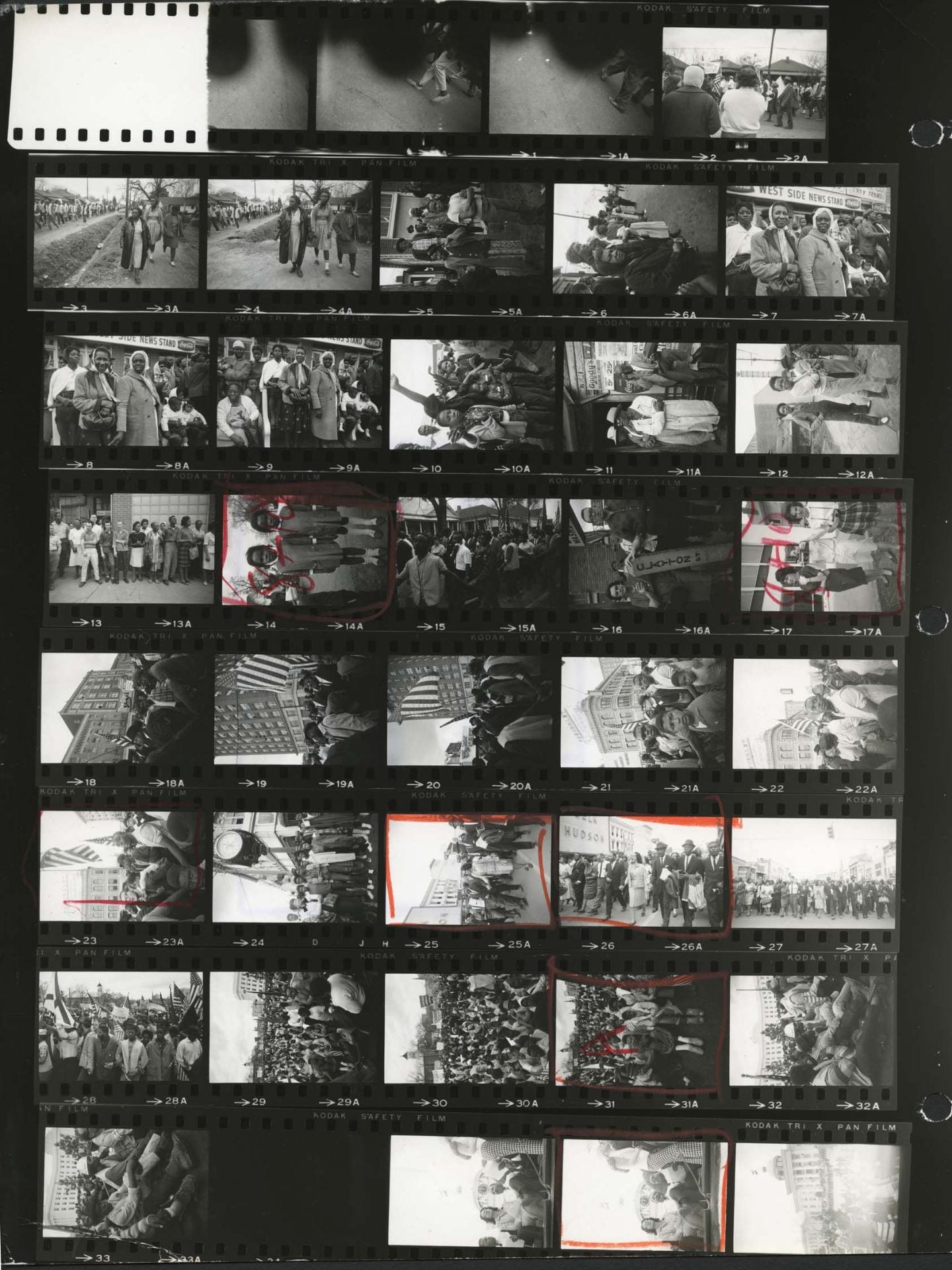

Magazine editors had particular ideas about how to depict the southern civil rights movement. As white, middle-class, northern men, they preferred photographs of particular male leaders (such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.). Schapiro also captured the women and working-class people who organized local communities, experimented with new ideas, and sustained activism beyond a particular march or speech. These images rarely got published. Editors also tended to select photographs that depicted African Americans as passive victims of southern white vigilante violence as a means to attract other white liberals to the integrationist civil rights cause. But this process also flattened the multidimensional ideas that activists generated. Such activists often declined to join the normative (white) society portrayed in Life. They wanted to transform American institutions altogether.

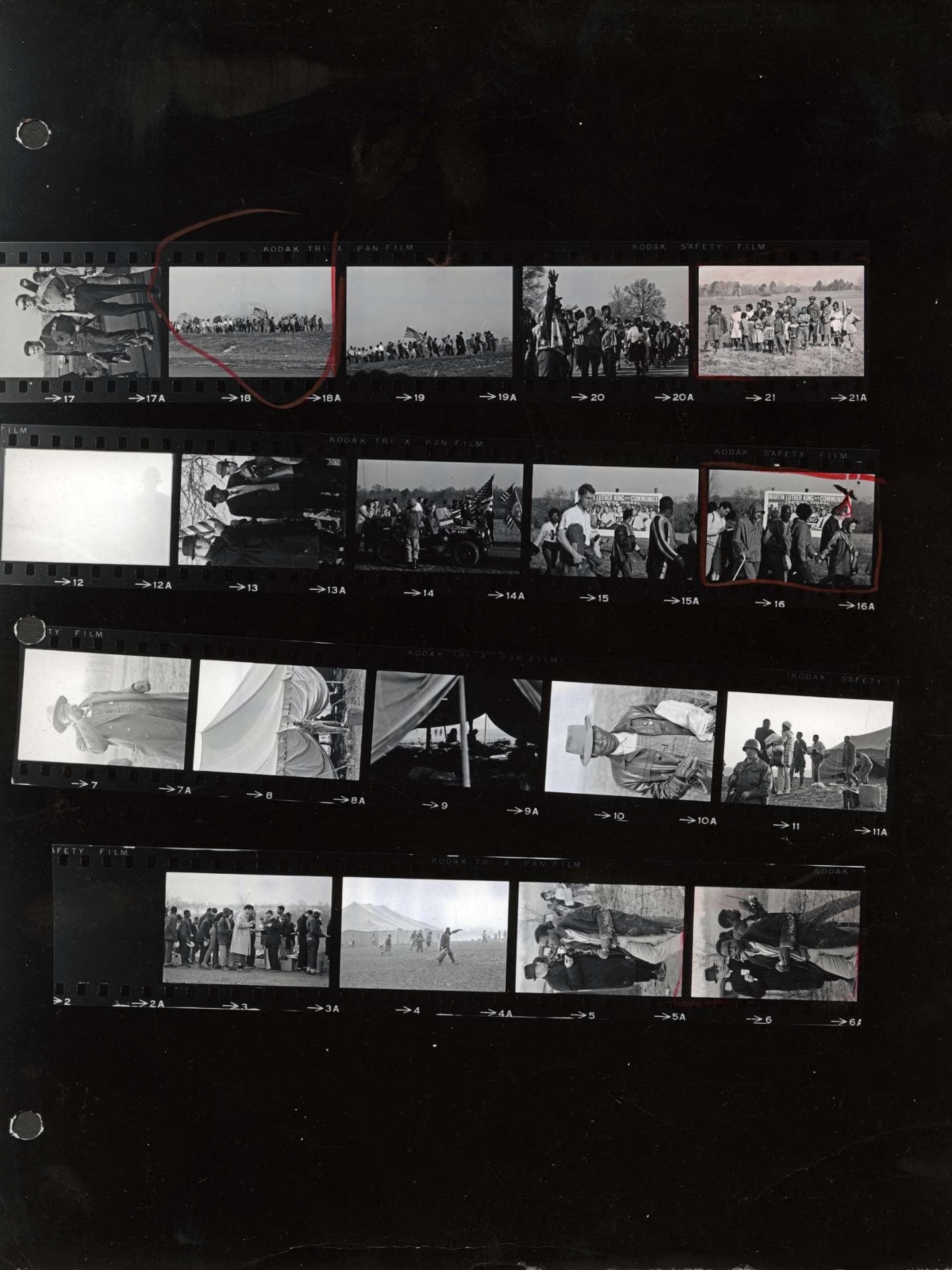

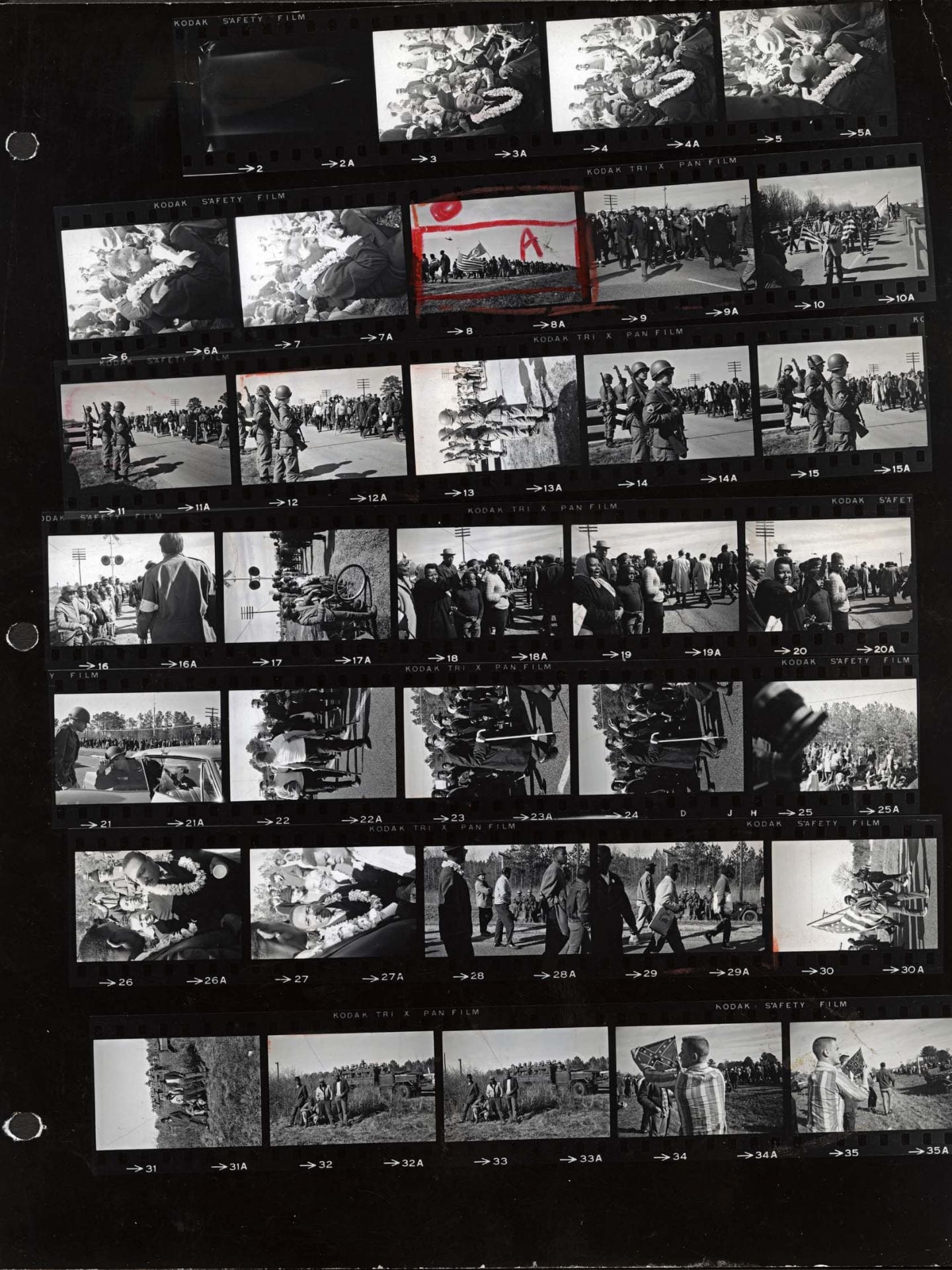

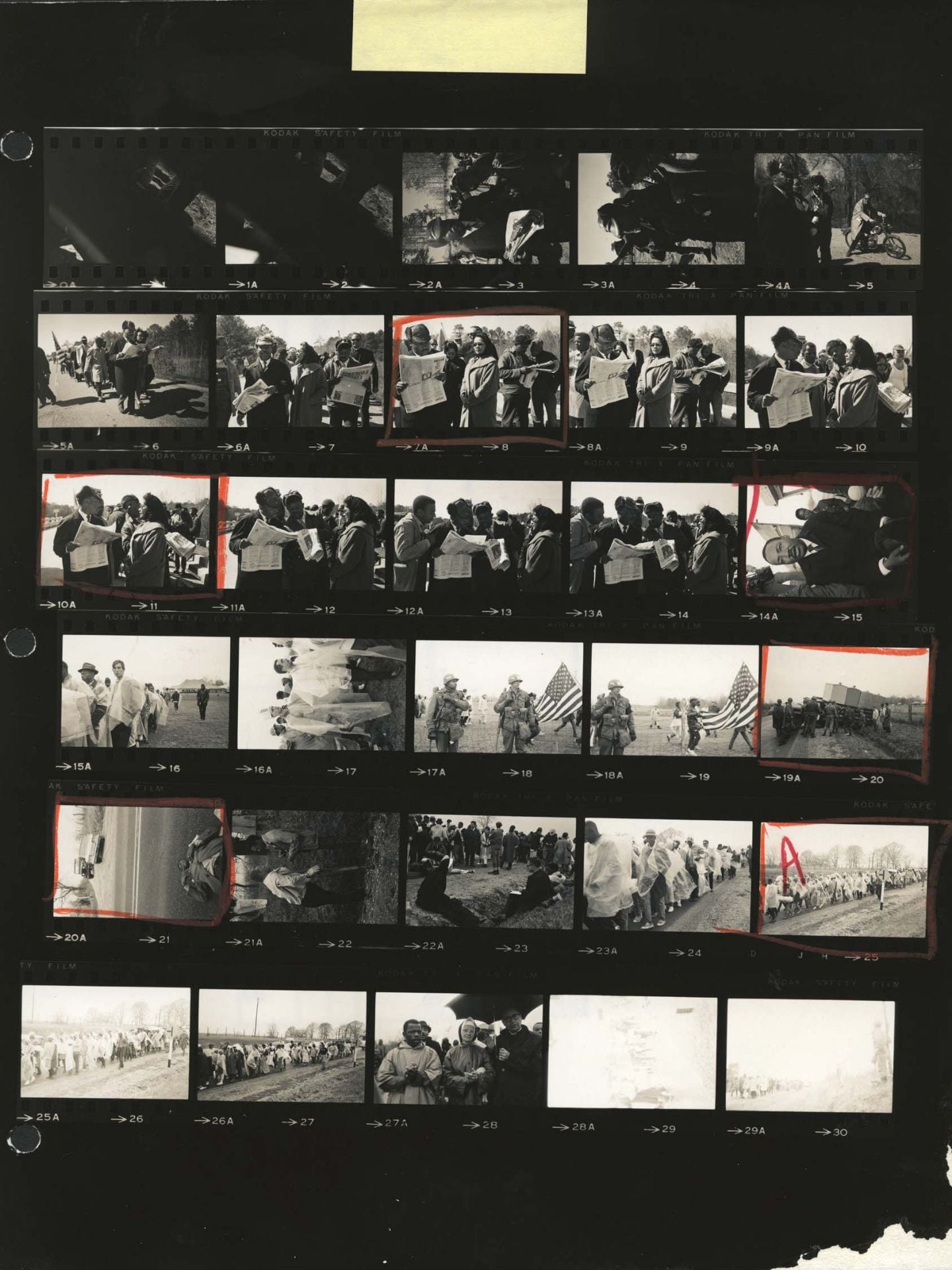

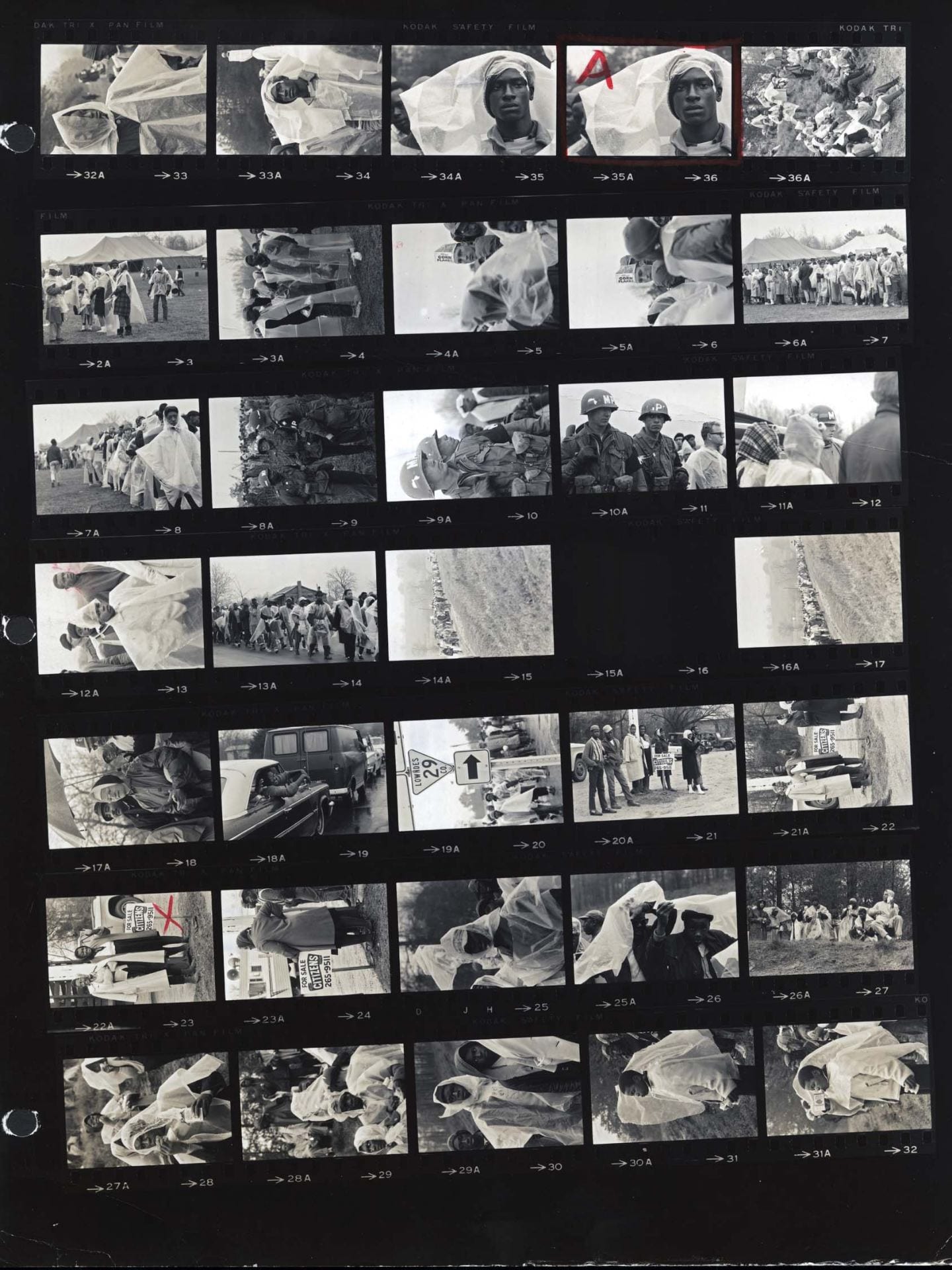

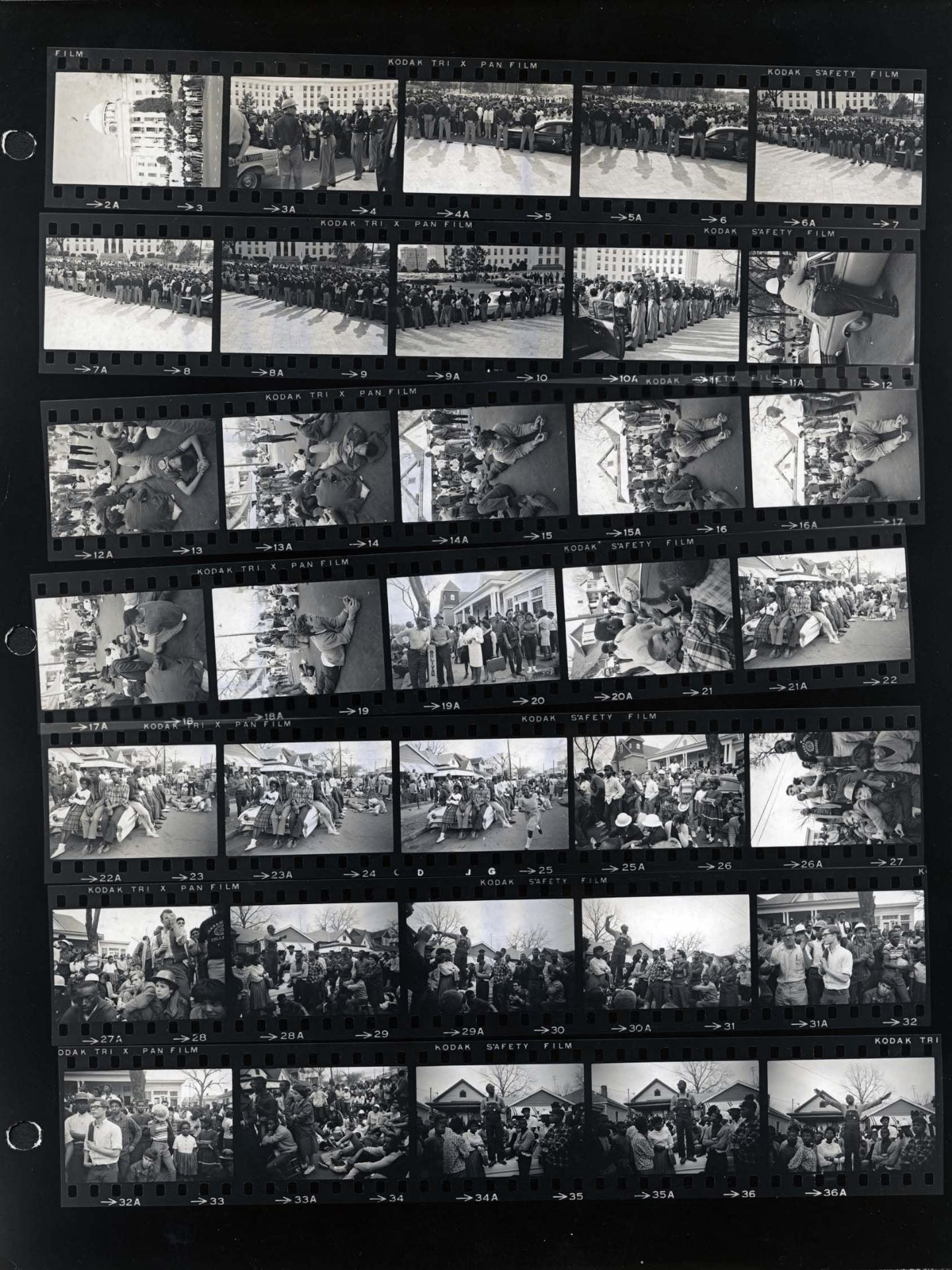

Schapiro’s contact sheets of the southern civil rights struggle between 1963–1965 thus offer a new, less filtered view of a movement many believe they know. The first set of photographs represents some of Schapiro’s earliest civil rights work, when he accompanied the writer, public intellectual and activist James Baldwin on a six-week tour through the South in 1963 (for a subsequent Life article). These contact sheets also capture grassroots organizing in Mississippi and Alabama. There, young people in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and Congress of Racial Equality joined with local people in pursuing racial justice in the most dangerous parts of the white supremacist South. Schapiro’s contact sheets reveal a spectrum of people and emotions — from dancing in New Orleans; to a music concert and freedom rally in Greenwood, Mississippi; to a hate rally led by white supremacist and terrorist J.B. Stoner in St. Augustine, Florida.

The second section of contact sheets reveals Schapiro’s artistry-at-work at one pivotal event — the March 1965 Alabama Voting Rights campaign. In sequence, they provide the feeling of marching the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery. The viewer sees a range of civil rights leaders embedded with the local people of Alabama who sustained their own fight for freedom and lived with the consequences. Put together, these contact sheets invite us to reexamine the photographic process, the historically rich content, and the artistry of Schapiro. Moving beyond the iconic images that mass media publications made famous, these frames offer a new, wider angle of insight into the activists who fought to expand our democracy a half-century ago and how they might inform our own imperiled times.

Below, please view select images from “Steve Schapiro: Civil Rights Era Contact Sheets,” which runs through December 22, 2018 at Roosevelt University’s Gage Gallery, open Monday to Friday, 9 a.m. – 12 p.m., and Saturday, 9 a.m. – 5 p.m. This free exhibition is open to the public.

More in this section

unexcused absence

Some of life’s most important lessons cannot be taught inside the four walls of a classroom. Matthew Beardmore’s travel has forced him to reassess how he thinks about work, family, politics, injustice and many other issues. He’s no longer tied to the beliefs of where he grew up.

traveling while home: self-discovery through the local

How can you make the long trip home if you don’t actually leave there? A partnership between Roosevelt University’s Honors Program and Chicago Architecture Center asks students to experience space and place as sites for action—not simply places we passively inhabit.

creating a new travel niche while wandering the globe

In early 2011, Sahara Rose De Vore bought a one-way ticket to Costa Rica. Over the next 10 years, she explored 84 countries. The self-discovery she experienced inspired her to launch two successful businesses—both helping others discover the benefits of travel.