An Interview with Dr. Carla Hayden (BA, ’73), the 14th Librarian of Congress

The Roosevelt honorary doctorate recipient discusses her career and time as a Lakerby JULIAN ZENG

On May 11, Roosevelt University presented an honorary degree to Dr. Carla Hayden during its spring Commencement ceremonies. Hayden, the 14th Librarian of Congress and first woman and African American to lead the national library, spoke about her time as a Roosevelt student, her career path in library science, and how the graduating students could maximize their potential for good.

Hayden was nominated by President Barack Obama in February 2016 and confirmed by the U.S. Senate in July that year. Prior to leading the Library of Congress, Hayden was nominated by Obama to be a member of the National Museum and Library Services Board in January 2010, and previously served since 1993 as CEO of the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore, Maryland. Hayden was president of the American Library Association from 2003–04 and became the first African American to receive Library Journal’s Librarian of the Year award in 1995. She received her bachelor’s in political science from Roosevelt in 1973, as well as her master’s and PhD from the Graduate Library School of the University of Chicago.

Hayden sat down with the Roosevelt Review to delve deeper into her personal journey and her goals of using technology to improve Americans’ access to knowledge and understanding of the world around them.

Roosevelt Review: Welcome back to Roosevelt University! We are really thrilled to have you here. What are your thoughts on being back at Roosevelt?

Carla Hayden: I was just thinking about how long it’s been since I’ve been to Roosevelt, and it’s been over 30 years, and maybe even longer. But when I walked in this time, I felt like it was almost yesterday. And even though there’s some new things here, a lot of wonderful things here, just the feeling of vitality and excitement, it sparked again.

RR: What first brought you to Roosevelt as a student?

“Librarians have been called ‘feisty fighters for freedom’: the freedom for everyone to have the opportunity to get knowledge.”

– Dr. Carla Hayden (BA, ’73)

Librarian of Congress

CH: Roosevelt … was almost a refuge because I had a rather disastrous first year in a small college in a kind of rural area, and that didn’t really take. And so, with Roosevelt, it was coming back home, being in Chicago again. I needed something to get me going, to get me interested in studying, or all of the above. And so, I enrolled and started taking classes. I took history because that’s what I had been interested in, but it was the political science courses that really sparked me and got me energized again. And so that’s what Roosevelt meant to me.

Frank Untermyer [late professor emeritus of political science and African studies] was the professor who really got me to think about what government is and what it could be and what the history of our own country, the United States, has been in terms of a more perfect union. And so that was what really got me interested in political science.

RR: What did you think you wanted to do after you graduated?

CH: I thought about possibly going to law school or maybe getting a master’s in social work. In the meantime, there were fiscal realities that meant I had to look for employment, but I was not employable because I didn’t have any practical experience. And that’s how I became the accidental librarian. Between job interviews, I would go to the Chicago Public Library — one of my colleagues who had just graduated from Roosevelt came in and said, “Carla, are you here for the library jobs? They’re hiring anybody!” And it was anybody with a bachelor’s degree, for a program called library associates.

I applied and the next I knew they assigned me to the South Side branch with a young lady who was going to the University of Chicago’s graduate library school. She had on jeans and was doing story time with children with autism, she was doing all of this cool stuff. And I thought, “Huh. Library science. What’s that about?” And that’s how I got into librarianship.

RR: How do you think libraries work as a social function? Would you say the work of a librarian is activist?

CH: I think I would use the word activism in its most positive sense because librarians have been called “feisty fighters for freedom”: the freedom for everyone to have the opportunity to get knowledge. There is essentially a reader’s bill of rights that librarians subscribe to, the idea that getting the right book in the right person’s hand at the right time can help a person. Help them to imagine, help them to do something in their lives. But the idea that you are actively providing something to someone that will hopefully help them in some way — entertain them, and that’s help too. People need escape.

RR: What about in the broader social dimension? What is the role of libraries in relation to the Patriot Act or the work you did in Baltimore?

CH: The work that I’ve been involved in, especially in Baltimore where the library was more of a community center and opportunity center, really emphasized how important a free, open library can be in a community. And not just urban areas, but rural areas — anywhere they are. People who are not only teaching their young people to read, but thinking beyond books to be parts of communities, that’s something that I knew firsthand in Baltimore. Libraries all over this country are pretty unique in that, and other countries are emulating it too.

“What you know now and all of the things you learned might not be what you need to know in the future. But what you have learned is how to learn and how to preserve. As you continue to invest in yourself and to continue learning, you can find meaning in purpose in work you might not even imagine now.”

– Carla Hayden, 2018 Roosevelt Commencement Ceremony

Librarian of Congress

RR: How did Roosevelt’s mission of social justice resonate with you?

CH: One of the things that really attracted me to the social mission of Roosevelt was its founding in honor of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. I learned about Eleanor Roosevelt in high school, a strong woman that when I found out about her, I said “Oh my goodness.” In terms of civil rights and her being an activist, being someone you could admire … the fact that this was a school that she actually had a hand in, that was very intriguing. It really emphasized that the people and graduates who went to this school were interested in helping other people in whatever way they could, and that was really appealing.

RR: You are the first woman and first African American to be the Librarian of Congress. What opportunities do you think you have, given that position?

CH: As the first female Librarian of Congress, it’s very meaningful in the library profession, because librarianship is one of the four, as they call them, “feminized” professions — nursing, education, social work and librarianship — where at least 85 percent of the workforce is female. Sometimes the top management of the institutions involved in those professions don’t reflect that. And so that has been very significant. As a person of color, it’s even more meaningful for me personally because of the history of African Americans and literacy, being punished by laws written to prevent them from reading. There’s been this really interesting disconnect with literacy, books and African Americans for a long time, and so to have a person of color, a descendant of people who were denied the right to read, to be leading the world’s largest library, has been an interesting aspect with younger people. I gave a presentation at a library conference for young academic librarians of all backgrounds. During the question and answer period, a young Asian librarian got up, she was emotional, and said “Seeing you lets me know what I can do.” And that’s really powerful.

“Please join me on a journey. Even though I’m a career librarian, I can’t know everything in this wonderful, wonderful institution.”

– Dr. Carla Hayden (BA, ’73)

Librarian of Congress

RR: How did President Obama persuade you to make the leap to Librarian of Congress?

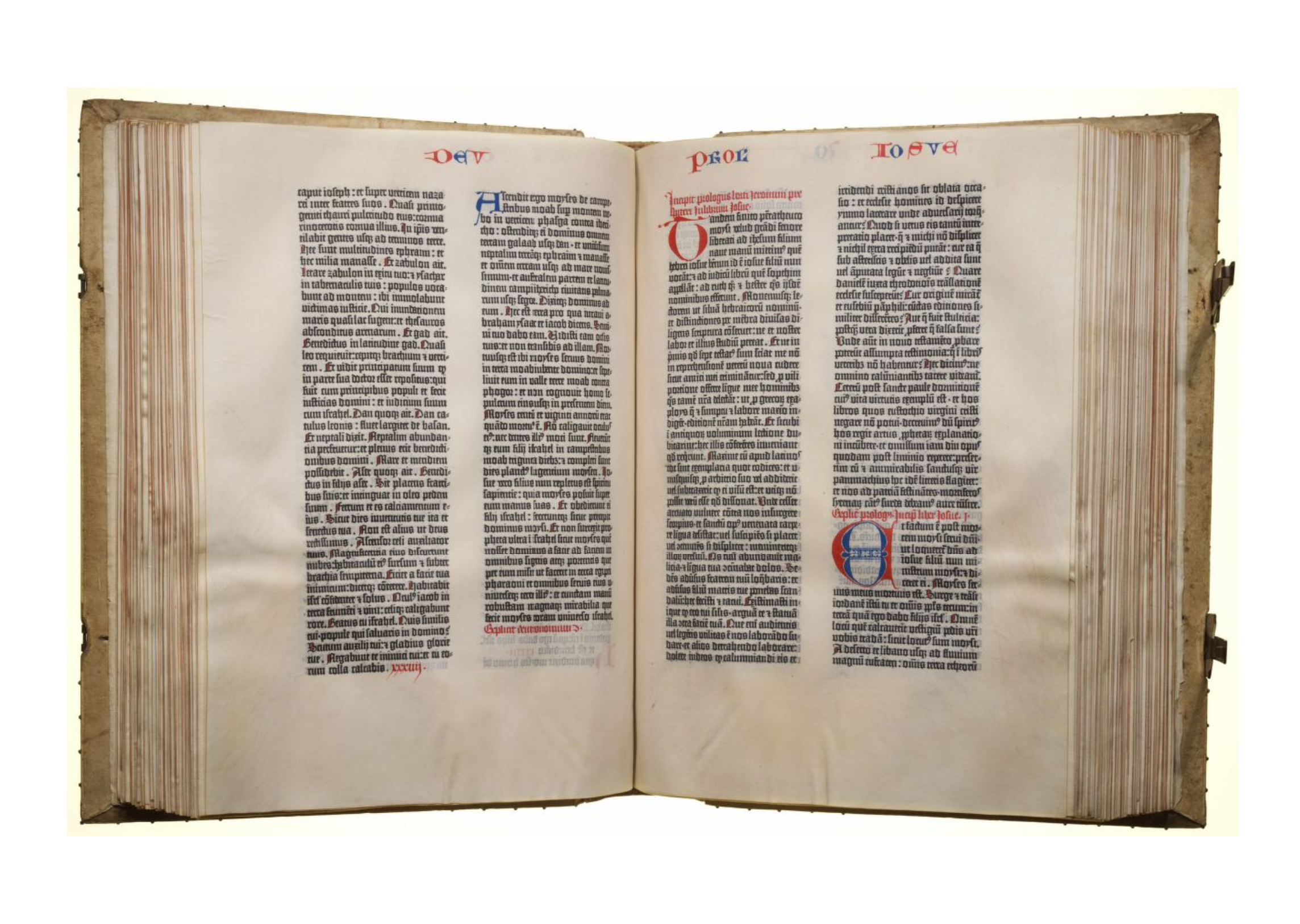

CH: As a librarian, I of course knew about the Library of Congress, the world’s largest library — it’s legendary. When I was asked to consider the position and how I could enhance the Library of Congress, President Obama convinced me that I might have something to offer because of all the treasures he had seen within the library: the contents of Abraham Lincoln’s pockets the night he was assassinated, Teddy Roosevelt’s diary, Lincoln’s reading copy of the Gettysburg Address that he took on the field, the Gutenberg Bible. He said, “I think some of it is because of who I am. What could you do to share these treasures and make sure more people could see them and appreciate what is in the Library of Congress?” I was hooked.

It’s been wonderful to work with the curators, the librarians and staff members, the knowledge that they have. You can pick any object, something from a thousand years ago to a digital copy that’s just come in, our staff knows everything about it. So, it’s been exciting to work with them and think about getting other people excited about history and creating things, getting that spark going. Just like I got here at Roosevelt.

RR: I understand that you’re the first Librarian of Congress who tweets. That’s just one digital mode of teaching people about the Library of Congress and showcasing its collections, but I think part of your agenda for sharing the treasures of the Library of Congress with the American people is through digital means. Can you talk a little bit about that?

CH: Well, part of my goal is to use technology in as many ways as possible, to extend the reach of these wonderful and unique collections. I started using social media as soon as I walked down from the stage after I was sworn in and said, “Please join me on a journey. Even though I’m a career librarian, I can’t know everything in this wonderful, wonderful institution.” Every day or so I’ll tweet and post on Instagram, and I’m discovering so many things by making that connection. And the response has really been something. It’s been wonderful to use technology as a tool to bring these collections to life and to more people.

RR: What would you like to see as your legacy with the Library of Congress?

CH: It’s interesting, we’re going through a strategic planning process now and thinking about the future.

What I would really like to see is that all Americans feel and know they could be connected to the Library of Congress, that they would be aware of it in some way. If that could happen — they hear Library of Congress and go, “Oh yeah, I ‘fill in the blank’” … that would be pretty cool. Social media helps!

RR: What about in the broader social dimension? What is the role of libraries in relation to the Patriot Act or the work you did in Baltimore?

CH: The work that I’ve been involved in, especially in Baltimore where the library was more of a community center and opportunity center, really emphasized how important a free, open library can be in a community. And not just urban areas, but rural areas — anywhere they are. People who are not only teaching their young people to read, but thinking beyond books to be parts of communities, that’s something that I knew firsthand in Baltimore. Libraries all over this country are pretty unique in that, and other countries are emulating it too.

RR: What are some of your favorite treasures? I saw you had Abraham Lincoln’s Bible when you were sworn in?

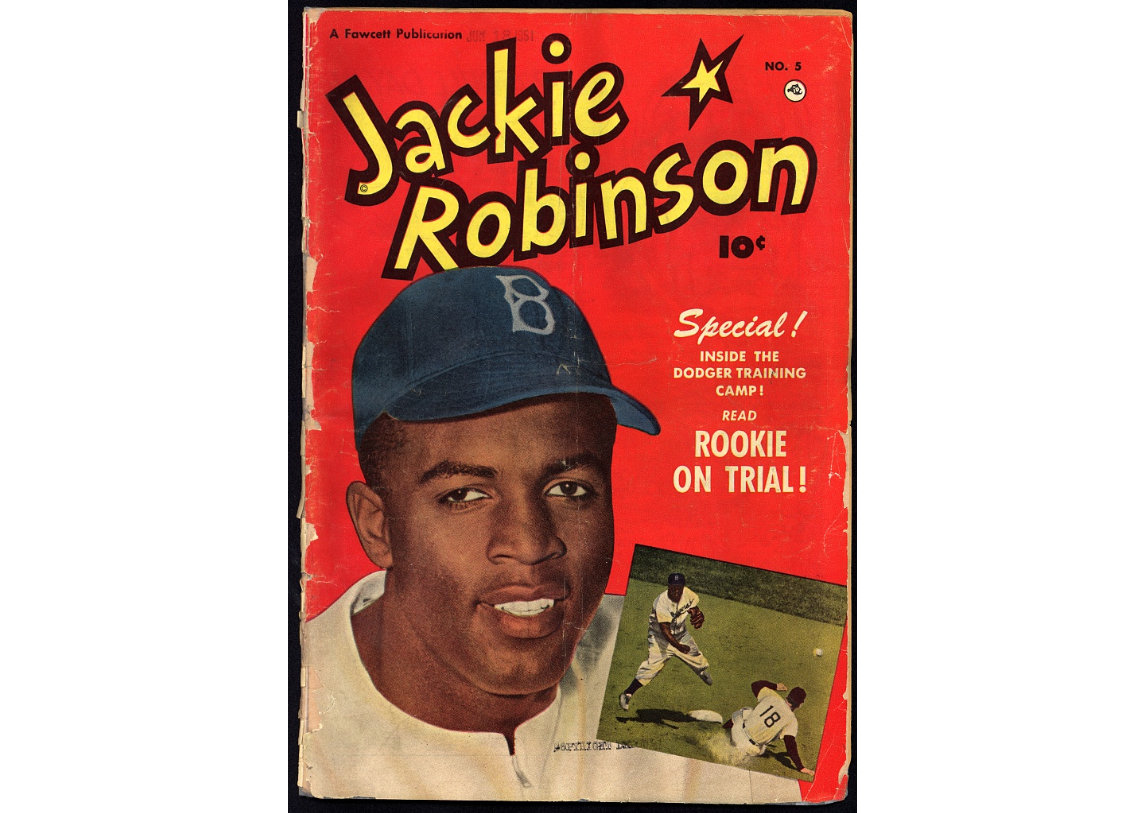

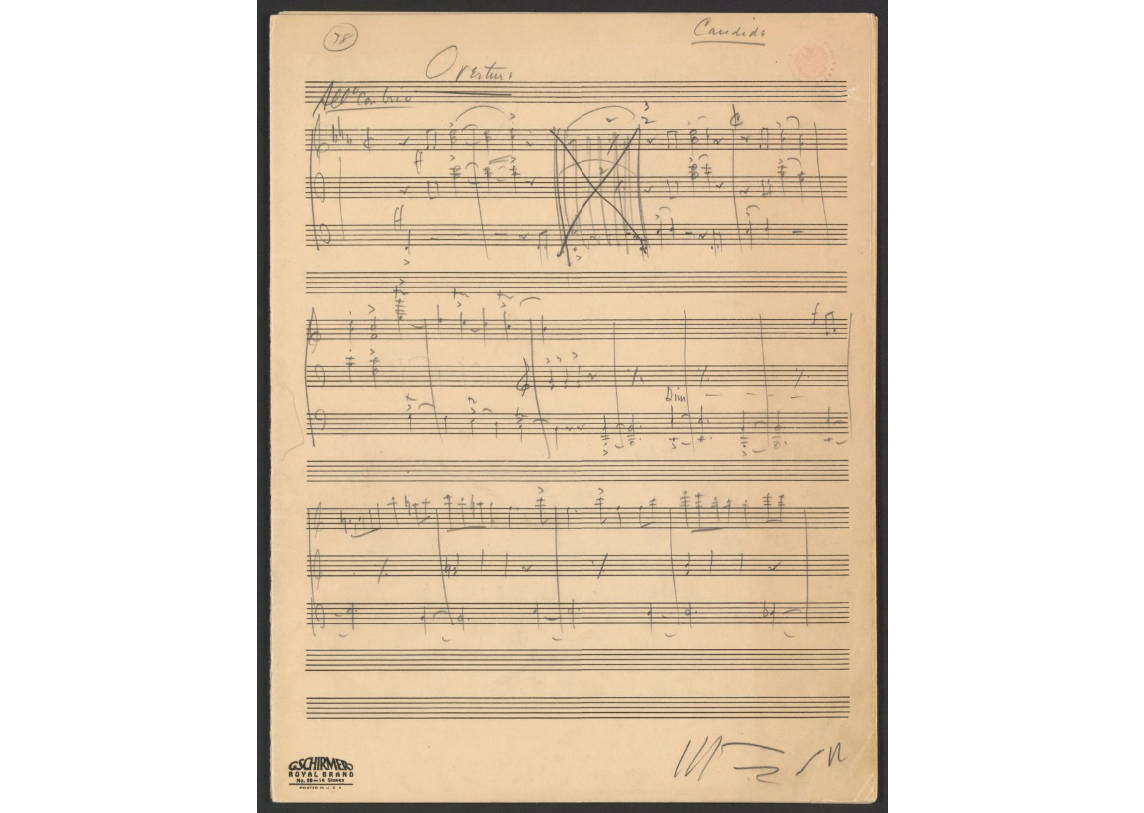

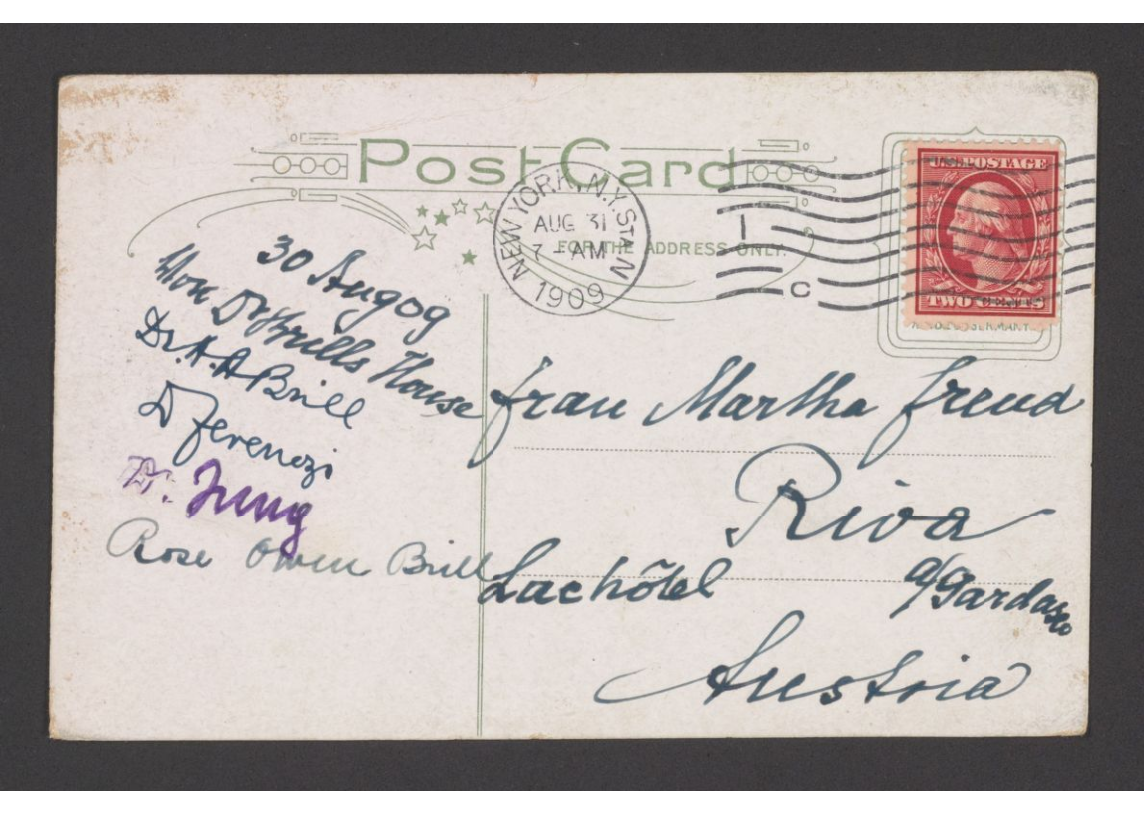

CH: Oh yes! The library has the largest collection of Bibles in the world and one of the three existing Gutenberg Bibles. The library has Rosa Parks’ Bible and her handwritten notes about how she felt about being arrested and things. Then you have musical scores by Mozart in his own hand, Leonard Bernstein’s collection, six Stradivarius violins, the largest collection of flutes, Jerry Lewis’s home movies. It’s kind of hard to pick your favorites. … Sigmund Freud’s papers were just digitized, his correspondence with Albert Einstein, Jackie Robinson’s collection.

RR: Never a dull moment.

CH: No, it’s fun, but that’s the whole thing we want to do! This is really wonderful, cool stuff. Hamilton’s last letter to Eliza — the kids love that!

More in this section

Seeds of Change in a Biodiversity Hotspot

Professor Norbert Cordeiro and Dr. Henry Ndangalasi are writing a book that will be an essential resource in the efforts to conserve the Eastern Arc Forests, one of the most biodiverse regions in the world.

President’s Perspective

I know that the list of problems we face as a University and as a nation is long. It is easy to give way to pessimism and despair, but that is when it is most important to choose optimism and hope.

Remote Learning in a State of Emergency

Professor Linda Pincham faced the same dilemma that educators are grappling with across the world as they try to make their courses matter in an ongoing crisis.