Millions of Americans recognize the work of Joel Schick (BA,’68). But like many illustrators, his name is not as well-known as his art — renderings of Cookie Monster, Big Bird and hundreds of other whimsical figures in nearly 80 children’s books, including Muppet and Sesame Street stories and illustrations for the beloved Wayside School and Magic School Bus series.

Schick’s first publication resulted from doodles created in Roosevelt University classrooms in the mid-1960s. “I was one of those students,” he said, “wearing blue jeans, an army jacket and sunglasses, sitting in the back of a class with my green denim book bag and drawing in the margins of my notebooks.”

Schick’s first publication resulted from doodles created in Roosevelt University classrooms in the mid-1960s. “I was one of those students,” he said, “wearing blue jeans, an army jacket and sunglasses, sitting in the back of a class with my green denim book bag and drawing in the margins of my notebooks.”

Schick applied to Roosevelt in 1965 after leaving Northwestern University and Augustana College due to disciplinary issues. Roosevelt’s admissions officer told him his test scores were good but he had poor grades and a record as a troublemaker. “There’s not a college in this country that would accept you with a record like this. Luckily for you we are running a special for draft-age men,” the admissions officer said and admitted Schick on the spot.

“I was given a second chance by Roosevelt . . . a school that gave me a break when I was down, and it very likely saved my life,” he said.

Schick had always been interested in art, remarking that “as a kid I was crazy about Donald Duck and Little Lulu, Disney animation and MAD Magazine.” But his high school art teacher told him, “Forget it, you don’t have enough talent to be an artist.” So Schick turned instead toward music and played in a band; while at Roosevelt, he was offered a job in New York City as a songwriter. However, not willing to lose his student draft deferment, he remained at Roosevelt until graduation.

“I was given a second chance by Roosevelt . . . a school that gave me a break when I was down, and it very likely saved my life.”

–Joel Schick

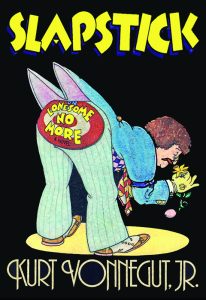

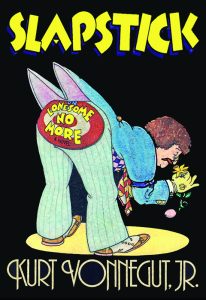

Schick’s cover design for Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.’s 1976 novel, “Slapslick.”

Like many Roosevelt students, he worked while going to school — loading planes at O’Hare, working as an auditor/night clerk at an Oak Brook hotel and counseling in a home for emotionally disturbed children in Evanston. He assumed he would enter a career in social services. But then he found work at a print shop, where he learned how art made its way from a client’s notion to publication. There he found his vocation.

His schedule was busy — attending morning classes, going to work and studying in the middle of the night. He was rarely on campus except for class, though he recalled reading the Torch and attending campus film festivals. After nearly half a century, he still can remember several of his professors, including Aurora Biamonte in psychology, Morris Springer in French (“I remember him better than I do French!”), and especially English professor Marilyn Levy, who taught public speaking and invited Schick to meet her husband, a graphic designer, at her home in Evanston, Ill.

Graduates in 1968

While earning a BA in psychology, Schick married Northwestern University student Alice Raffer, who became an editor and writer and a collaborator on many projects. In 1968 he graduated. “I am deeply grateful to Roosevelt,” he said. “I felt that it actually cared about my wellbeing. And I came out a lot better than I went in.”

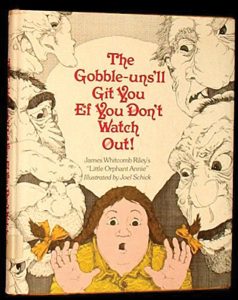

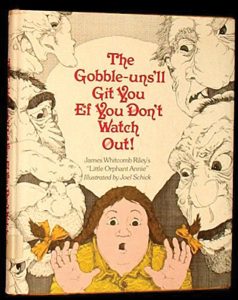

Detail and cover from the award-winning book “The Gobble Uns’ll Git You, Ef You Don’t Watch Out!”

Joel and Alice moved to New York with a portfolio of cartoon marginalia from his Roosevelt notebooks. There he sought design work with book publishers and began a career with such publishing houses as Holt Reinhart and Winston, Random House, Delacorte and Dell. During those years, he designed hundreds of books and book jackets. He was especially excited to design several Kurt Vonnegut books, including Breakfast of Champions, and Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez. Both books won the National Book Award.nHe also remembers spending afternoons at Vonnegut’s house, discussing projects, watching the Nixon impeachment hearings and meeting a new young author — John Irving.

Drawing for Children

“Designing books was great fun, but I wanted to draw, to illustrate for children,” he said. In the mid 1970s the Schicks moved to western Massachusetts where they created books together and raised their son Morgan. Joel also became art director for the Bank Street College of Education, developing board games, pre-school text programs, retail marketing and corporate branding.

His first children’s trade book illustration came out in 1974 and embellished an 1885 poem by James Whitcomb Riley, published as The Gobble Uns’ll Git You, Ef You Don’t Watch Out! It was an award-winning hit. He then began getting calls to illustrate other children’s books. “I became the go-to guy when publishers wanted someone to bring a little humor to a manuscript,” he said.

In the 1980s he and Alice created a newspaper comic strip, which, while it didn’t make it into print, caught the eye of Muppet illustrator Tom Leigh. Leigh had collaborated on previous projects with Joel and Alice and when he began working for Sesame Street introduced Joel to his contacts. “It was a match made in heaven,” Leigh remembered.

Although Schick had no formal art training, Leigh said, “He drew and painted very well, and understood form and spatial relationships, which helped him easily assimilate how the characters were built and how they moved.” What really set Joel’s work apart, Leigh added, “was the sense of joy and animation he drew from these characters.”

Artist James Mahon, the former creative director for Henson Associates and Sesame Street, said that Schick’s illustrations “reflected the bright, cheerful enthusiasm of the Muppets and also the human foibles of many of them. An artist puts ideas into form and working with Joel allowed us to explore more complex things.”

Muppets and More

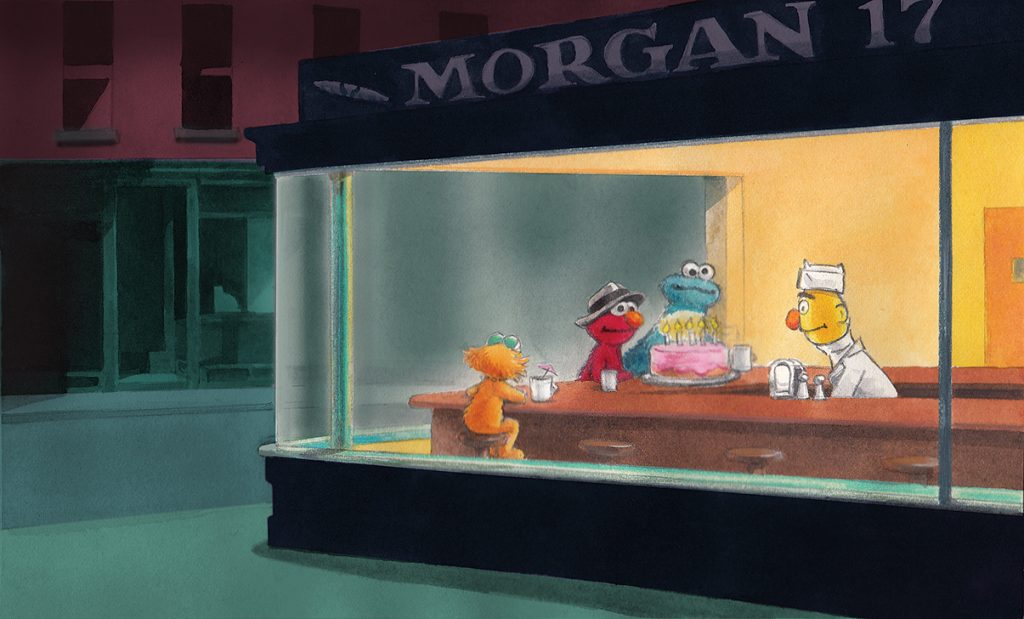

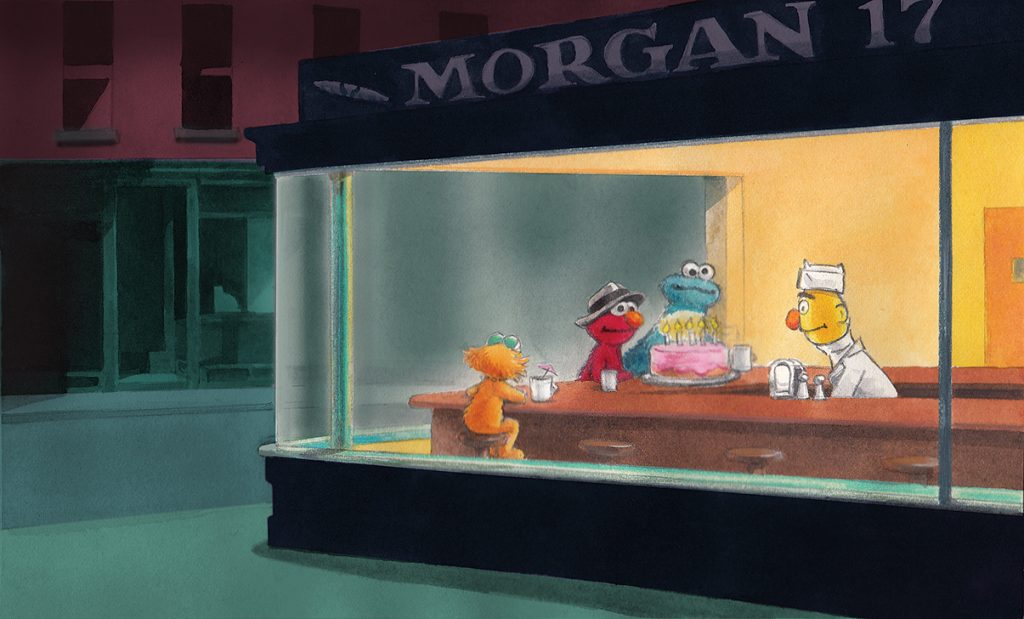

Edward Hopper: Nighthawks on Sesame Street

For 15 years Schick created images of Kermit, Miss Piggy, Gonzo, Elmo, Big Bird, Cookie Monster and Grover. He illustrated Muppet books, Sesame Street magazines, products and packaging. “I loved this work,” he said, “because it required that I learn how every product was manufactured, what limitations the manufacturers faced and how to work within and around those limitations.”

At that time Muppet creator Jim Henson insisted that every Muppet product feature a new piece of art, and there were hundreds of products requiring hundreds of pieces of art — and only about a dozen artists in the world were permitted to draw the characters.

While working with the Muppets, Joel continued to collaborate with Alice on picture books, comic strips, a public school reading program and a website. “And all along, “he said, “I kept doing design, not just books, but advertising, packaging, posters, toys. All sorts of fun projects for paying clients and also pro bono work for animal causes, schools and a public theater.”

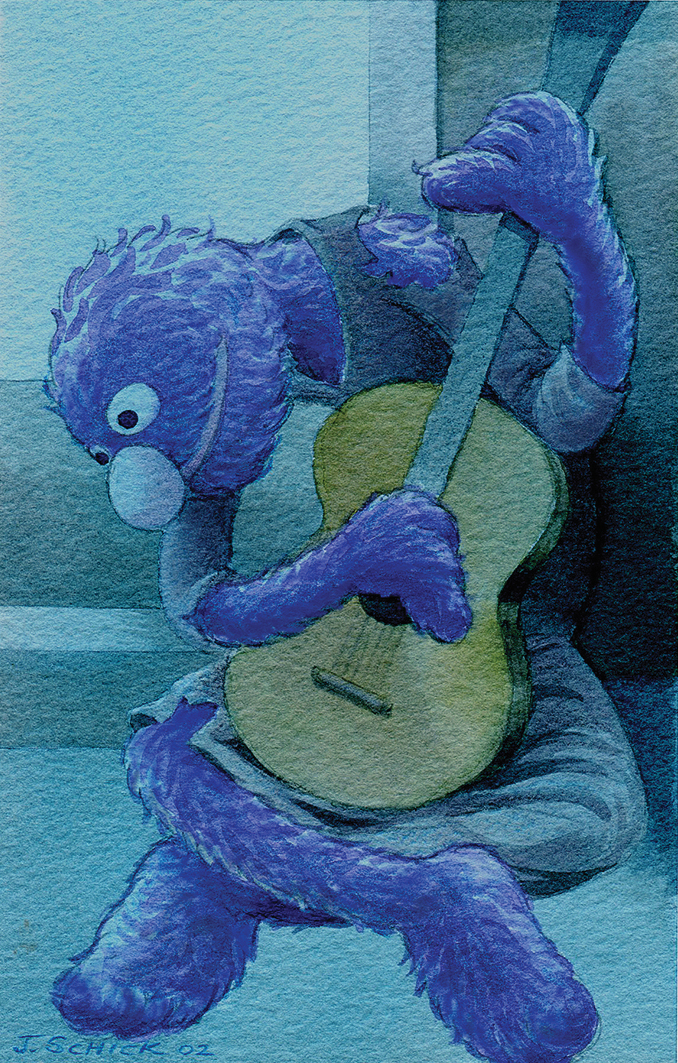

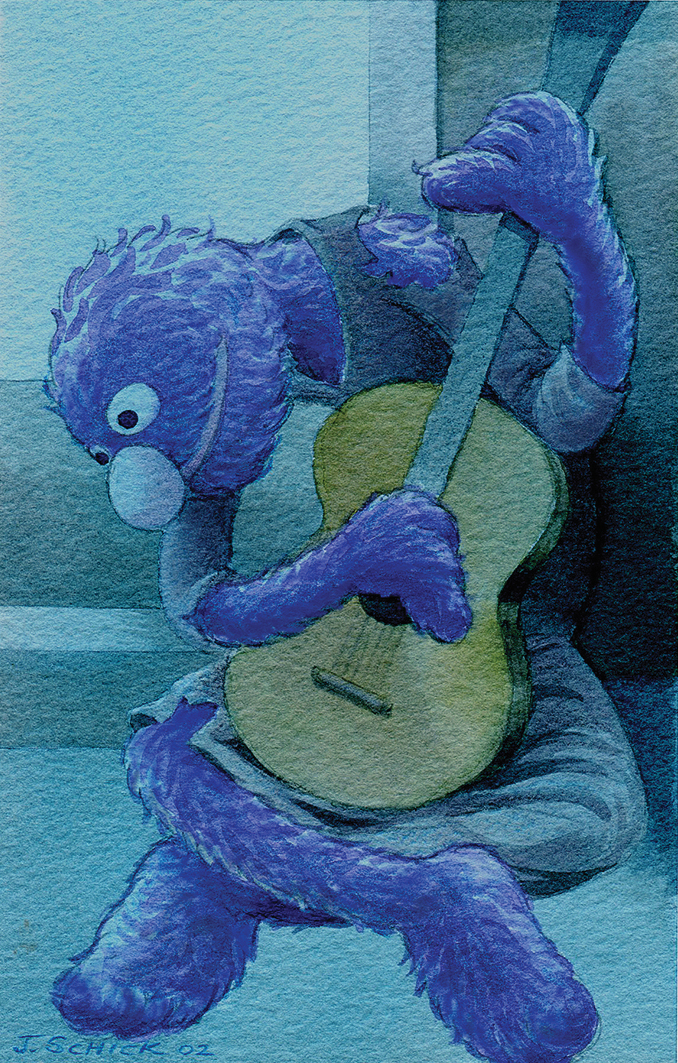

Pablo Picasso: Old Guitarist (Furry Blue Period)

His trade book illustrations have been honored with many awards, including a Wisconsin Golden Archer Award (voted on by middle school students), a New Jersey Book Award, and a Caldecott Honor award. His career was also recognized in 2012 by the W.E.B. Du Bois Center in Great Barrington, Mass., with a show titled “Bein’ Green: Why Every Color is Beautiful: An Exhibition of Original Muppets Artwork by Illustrator Joel Schick.” He also created a series of popular art parodies, featuring Muppets at the center of well-known paintings, including Grover as Thomas Gainsborough’s Blue Boy, Elmo and Zoe in Jan Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Marriage, and Telly in Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

Just as satisfying have been the numerous letters from young readers. “One of the joys of illustrating children’s book is the contact with kids,” said Schick. Six-year-old Randy Cecil in 1975 created a puzzle based on one of Schick’s illustrations. The two corresponded several times through the years and Cecil grew up to become an artist who has now illustrated over 20 children’s books.

Other fans included Michael, who wrote in 1981 that “I thought my brother was a good artist but he’s nothing compared to you.” Christian liked the pictures in Schick’s adaptation of the monster in Frankenstein, but believed that Schick missed something crucial — there was supposed to be “a steal piece stuck threw his head!” (Christian still had to learn some spelling techniques), and Devin, who wanted to emulate one of the Wayside School book characters with a tattoo, which Joel was happy to draw for him.

Other fans included Michael, who wrote in 1981 that “I thought my brother was a good artist but he’s nothing compared to you.” Christian liked the pictures in Schick’s adaptation of the monster in Frankenstein, but believed that Schick missed something crucial — there was supposed to be “a steal piece stuck threw his head!” (Christian still had to learn some spelling techniques), and Devin, who wanted to emulate one of the Wayside School book characters with a tattoo, which Joel was happy to draw for him.

Schick no longer illustrates books but has returned to music — writing songs, singing, playing harmonica and guitar, and producing CDs. He has written almost 400 songs and finds a connection between art and music. According to Joel, both art and music are “about a desire to entertain, to communicate with an audience.” Samples of his songs and art are available on the website he and Alice established to make their work available: FamilyGorilla.com.

And he hasn’t forgotten the university that took him in. “I love Roosevelt . . . they treated me like an adult,” he said. “They allowed me to decide how much I would or could integrate into the RU community . . . they offered me everything I needed for a college education.”

Roosevelt Archives 2015

In November 2015 Schick visited Roosevelt and donated his papers, books and original artwork to the library. “The Roosevelt University Archives is thrilled to house Joel Schick’s collection,” said archivist Laura Mills, “especially since the artwork will enhance our collection of award-winning children’s books.” Among the items donated are sketches, correspondence, original art and even some of Schick’s old Roosevelt notebooks complete with doodles.

The Joel Schick Collection, Schick hopes, will show how people really produce art: by refining, redrawing, re-imagining, editing and discarding. And, he suggests, the collection “is important because I’m not famous. I’m a good illustrator, but not a famous one. Millions of kids have read the Wayside School books I illustrated, millions of people have seen my Sesame Street art. But nobody knows the artist.”

“The Roosevelt University Archives is thrilled to house Joel Schick’s collection, especially since the artwork will enhance our collection of award-winning children’s books.”

-Laura Mills, Roosevelt Archivist

Schick believes there are three kinds of illustrators. On the top are a few celebrities, like Maurice Sendak or Robert McCloskey, who had the financial resources to spend long periods of time on single projects and make each book an important publishing event. At the other end of the spectrum are a great number of artists who draw a book or two and then leave the business when they can’t make a living at it.

And in the middle, Schick suggests, “there are the people like me, journeymen illustrators, who work at it all their careers.” They have to work on several books at one time to make a living, draw in many styles and media, realize other people’s ideas and negotiate artistic visions with the client. “We have the soul of an artist, yes,” Schick said, “but also the soul of a tradesman, a cabinetmaker, perhaps or machinist – the soul of a tinkerer and the soul of a hunter-gatherer.”

And in the middle, Schick suggests, “there are the people like me, journeymen illustrators, who work at it all their careers.” They have to work on several books at one time to make a living, draw in many styles and media, realize other people’s ideas and negotiate artistic visions with the client. “We have the soul of an artist, yes,” Schick said, “but also the soul of a tradesman, a cabinetmaker, perhaps or machinist – the soul of a tinkerer and the soul of a hunter-gatherer.”

This last group creates, he said, “a lot of the art we see in children’s books – the art we all grow up on, the art that helps us learn to read, the art that illustrates our fantasies.”

This art is created by successful, talented, familiar, but largely anonymous artisans. Like Joel Schick.

“Sesame Workshop”®, “Sesame Street”®, and associated characters, trademarks, and design elements are owned and licensed by Sesame Workshop. © 2016 Sesame Workshop. All Rights Reserved.”

Schick’s first publication resulted from doodles created in Roosevelt University classrooms in the mid-1960s. “I was one of those students,” he said, “wearing blue jeans, an army jacket and sunglasses, sitting in the back of a class with my green denim book bag and drawing in the margins of my notebooks.”

Schick’s first publication resulted from doodles created in Roosevelt University classrooms in the mid-1960s. “I was one of those students,” he said, “wearing blue jeans, an army jacket and sunglasses, sitting in the back of a class with my green denim book bag and drawing in the margins of my notebooks.”

Other fans included Michael, who wrote in 1981 that “I thought my brother was a good artist but he’s nothing compared to you.” Christian liked the pictures in Schick’s adaptation of the monster in Frankenstein, but believed that Schick missed something crucial — there was supposed to be “a steal piece stuck threw his head!” (Christian still had to learn some spelling techniques), and Devin, who wanted to emulate one of the Wayside School book characters with a tattoo, which Joel was happy to draw for him.

Other fans included Michael, who wrote in 1981 that “I thought my brother was a good artist but he’s nothing compared to you.” Christian liked the pictures in Schick’s adaptation of the monster in Frankenstein, but believed that Schick missed something crucial — there was supposed to be “a steal piece stuck threw his head!” (Christian still had to learn some spelling techniques), and Devin, who wanted to emulate one of the Wayside School book characters with a tattoo, which Joel was happy to draw for him. And in the middle, Schick suggests, “there are the people like me, journeymen illustrators, who work at it all their careers.” They have to work on several books at one time to make a living, draw in many styles and media, realize other people’s ideas and negotiate artistic visions with the client. “We have the soul of an artist, yes,” Schick said, “but also the soul of a tradesman, a cabinetmaker, perhaps or machinist – the soul of a tinkerer and the soul of a hunter-gatherer.”

And in the middle, Schick suggests, “there are the people like me, journeymen illustrators, who work at it all their careers.” They have to work on several books at one time to make a living, draw in many styles and media, realize other people’s ideas and negotiate artistic visions with the client. “We have the soul of an artist, yes,” Schick said, “but also the soul of a tradesman, a cabinetmaker, perhaps or machinist – the soul of a tinkerer and the soul of a hunter-gatherer.”