A philosophical approach

By Carla Beecher

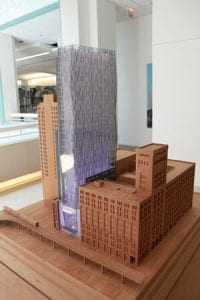

In fall 2012, Roosevelt University’s Wabash Building opened — making history as the second tallest academic facility in the United States. As described in Architect Magazine, “the new ‘vertical campus’ is composed of connecting neighborhoods of student services, student union, academic and student residential environments, which emphasize the ‘out of class’ spaces vital to a University atmosphere.

The stories that follow explore how the Wabash Building shapes the day-to-day experiences of Roosevelt’s students and faculty.

The Wabash Building is a physical representation of the university’s mission. When principal architect-designer Christopher Groesbeck, AIA, began conceptutalizing the building in 2008, he looked to Roosevelt’s founding mission as a central guide to create a space that was welcoming to all. What he and his team produced was an award-winning, LEED-certified green building of 32 stories that, in addition to reflecting the undulating green and blue colors of the lake in its windowed facade, also echoes the university’s desire to educate the next generation of citizens and inspire them to lead lives of purpose.

To do this, Groesbeck pulled together many competing elements. His considerations included erecting a vertical campus on a relatively small 17,000-square-foot plot of land; connecting the building functionally and aesthetically to the landmark Auditorium Building; providing ease of access throughout the space to efficiently bring together students, faculty, and administrators; designing large, open spaces for classroom and community as well as flexible smaller ones that could easily be combined or expanded; visually connecting its interior space to the city outside; and keeping sustainability and energy conservation front of mind.

When Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin reviewed the building in 2012, he picked up on Groesbeck’s desire to infuse the building with the idea that education is transformative, saying that the form was reminiscent of the stacked rhomboids of sculptor Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column. “The idiosyncratic shape expresses the idea that education transforms students and is never truly complete,” Kamin wrote.

The beginning

“The present learns from the past and looks forward. We gained the confidence and trust in this direction from then President Charles Middleton, Provost James Gandre and the university board.” — Christopher Groesbeck, AIA, principal architect

Roosevelt has a unique history dating back to 1945 when its leader, E.J. Sparling, and 62 like-minded faculty members refused to follow the discriminatory practices at the time of enforcing racial and religious quotas. They resigned their posts en masse from Central YMCA College to start a new university. From the start, Roosevelt’s vision was to accept everyone no matter their race, religion or beliefs, with a mission based in social justice.

Soon thereafter, Roosevelt University found a home in the Auditorium Building, whose architects, Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan,

“were transcendentalists whose work sought balance, harmony with nature and a natural order,” … “If you look at the building, it goes from its very rough, heavy stone base to a finer sort of cut, to finally the service tower on top, which is the most delicate: It balances heaviness with lightness. Its forthrightness aligns with Roosevelt’s transcendental mission of equality, and we connect the older building with the future through the Wabash Building. The Auditorium was our inspiration.”

“While the Auditorium inspired us, we did not want to diminish the power of the original by mimicking its color or language, so instead used its strategy of gradation — in this case reversing the pattern from dark on top to lighter as it approached the ground,” said Groesbeck.

They also realized, however, that building such a tall structure on a mid-block site is not typical in Chicago. “Usually, these bigger buildings take up almost a whole block or are on a corner. So, we knew we couldn’t build directly against the Auditorium because our foundations needed to be different, so we set the building back and hung a connector between the two structures on the second level.”

Viewing the building as a whole, its repeated form from the sidewalk to the roof plays on the idea that the Wabash Building is growing out of its context. “It reflects the mission of the school to offer students who might not have had the opportunity to enroll here the chance to transcend into a different life,” said Groesbeck. “That’s how we interpreted the idea of social justice through the building. It really is a process of transcendence.”

They didn’t anticipate that unlike a horizontal campus with separate buildings where students would rarely encounter their teachers outside of the classroom, that the elevator and stairwells would mingle everyone together.

“It’s actually a unique phenomenon to mix the students with the administration and professors outside of class,” Groesbeck said. “It ended up being one of the building’s most unexpected yet best parts.”

Viewing the building as a whole, its repeated form from the sidewalk to the roof plays on the idea that the Wabash Building is growing out of its context. “It reflects the mission of the school to offer students who might not have had the opportunity to enroll here the chance to transcend into a different life,” said Groesbeck. “That’s how we interpreted the idea of social justice through the building. It really is a process of transcendence.”

Read about student life in the Wabash Building

More in this section

American Dream Reconsidered Conference 2018

The third annual American Dream Reconsidered Conference was held Sept. 10–14, 2018, headlined by keynote addresses from Eric Holder, the 82nd Attorney General of the United States, and hip-hop artist and actor, Common.

President’s Perspective

President Ali R. Malekzadeh reflects on Roosevelt University’s recent milestones.

Steve Schapiro: Civil Rights Era Contact Sheets

The reopening of Roosevelt’s Gage Gallery in October featured never-before-seen works of acclaimed photographer Steve Schapiro, with large displays of rare contact sheets that captured the spirit of the Civil Rights Movement.