Part 1: Pre-Composition

I am a composer and a teacher. As a composer, I write music for chamber ensembles, choirs and orchestras. My recent works include Mythology Symphony, which had its world premiere by Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts Orchestra in January 2015 (and will be commercially released by Cedille Records in November 2015) and Terra Nostra, a large-scale oratorio for two choirs, four soloists and a chamber orchestra, which will receive its world premiere in November 2015 in San Francisco. Along with composing, I thoroughly enjoy teaching. Since September of 2000, I have taught composition and orchestration to undergraduate and graduate students in the Chicago College of Performing Arts.

At performances of my music, I am frequently asked how I compose. Do I hear it all in my head? Do I use computers to assist me? Have I ever experienced writer’s block? These are excellent questions, all of which I will address as I de-mystify the composing process. The following steps and strategies are not only what I use when I compose, but also what I teach my composition students.

For me, the first stage of beginning any new piece is research. This stage involves studying other composers’ works, as well as familiarizing myself with the particular instrumentation for which I’ll be composing. For instance, when I wrote Helios for brass quintet (an ensemble that consists of two trumpets, horn, trombone and tuba), I became acquainted with the ensemble by studying brass quintet repertoire, listening to recordings and attending live concerts. These activities helped me to ascertain the ensemble’s strengths and weaknesses, as well to as detect possible performance issues (the tuba, for instance, needs a lot of air to produce sound and performers tire quickly, so a composer must leave ample time between passages for the musician to breathe). The more I understand how the ensemble works, the better I’ll be able to compose for the group.

Along with conducting research, I brainstorm about possible sources of inspiration. When a work is commissioned, I find out from the commissioners what their interests are and incorporate these interests into my brainstorming process. In the case of Noir Vignettes, my double bass and piano piece, the commissioner told me of his fondness for movies, and of his particular interest in the director Alfred Hitchcock. I watched Hitchcock’s Vertigo and Rebecca and, while I didn’t care for Hitchcock’s filmmaking style, I became very intrigued with film noir, the genre for both of these movies. I watched several more movies in this style, including The Lady from Shanghai, Double Indemnity, This Gun for Hire and The Maltese Falcon. After watching each movie, I wrote down my thoughts on various aspects; for instance, a femme fatale could have an exotic, enchanting sound, whereas a gumshoe detective smoking his last cigarette of the day should sound slow and jazzy. Alternately, if the commissioner wants me to choose the work’s topic, I select a subject that is of personal interest to me. Recent topics include the Greek myth of Icarus, the boy who flew too close to the sun, and a depiction of the starkness of Wyoming’s landscape.

Self-doubt and high expectations can make it difficult for a composer to compose.

At some point during the brainstorming stage, I start putting pencil to paper. This can be a rather daunting moment. What if the notes I write down aren’t interesting? How can I possibly fill up the entire page with thought-provoking, well-conceived music? Self-doubt and high expectations can make it difficult for a composer to compose. To aid myself through this part of the writing process, I use a strategy: whenever I begin a new piece, I write one minute of music a day for seven days. It doesn’t have to be a great minute of music, or even a good minute, but it has to be one full minute. The music need not be continuous – I can compose three different ideas, each 20 seconds long. Giving myself permission to compose without judgment is an essential element of the strategy. While the first few days of composing are typically challenging, I eventually produce ideas that have real potential. I also get increasingly focused on how to creatively use the instruments.

Once I have written several minutes of music, the sorting process begins. I select the strongest, most intriguing ideas and start to flesh them out further. To do this, I analyze the musical material from every angle. What musical pitches comprise the melody? What are the intervals between each set of pitches? How would it sound if I turned the intervals upside down or reversed their order? Can I extend these ideas into longer phrases? What if I move the pitches higher or lower? I will often cover entire tabloid size pieces of paper with various configurations of each musical idea and refer to these papers throughout the entire composing process when I need more material from which to draw. As my musical materials become more substantial, I create the overall formal structure, or “roadmap,” of the entire piece. Having a roadmap is critical, for how can a piece have direction if you don’t know where it is going? Building from the musical materials that I’ve been developing, I draw a graph for the work with the x-axis representing time and the y-axis representing the level of tension in the music. The graph can show many other elements as well: how many sections or movements the piece will have, what musical characteristics each section or movement will contain and so on.

Part 2: Composition

Once I’ve developed enough pre-compositional work, I delve completely into composing. This is the most exhilarating stage of the process as I am entirely engaged in sketching and developing my musical materials into full sections. For a while, I am conscious of every decision that I make while composing; however, the further I get in composing a piece, the more these decisions are being made subconsciously. I tend to write faster as this process moves along, as well as find it difficult to do anything but compose once I’ve fully hit my stride. Going to concerts, seeing friends for dinner, running errands – all of these can break my concentration on the piece and make it hard to resume where I left off. As a result, I generally find it easier to compose in large blocks of time, usually anywhere from two to four hours. Once I’ve reached a natural resting place, such as a break between sections or the end of the movement, then I will stop for the day.

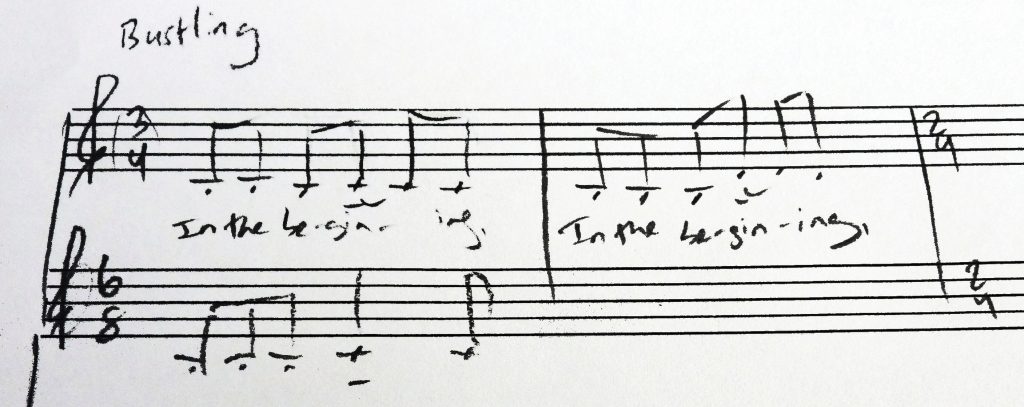

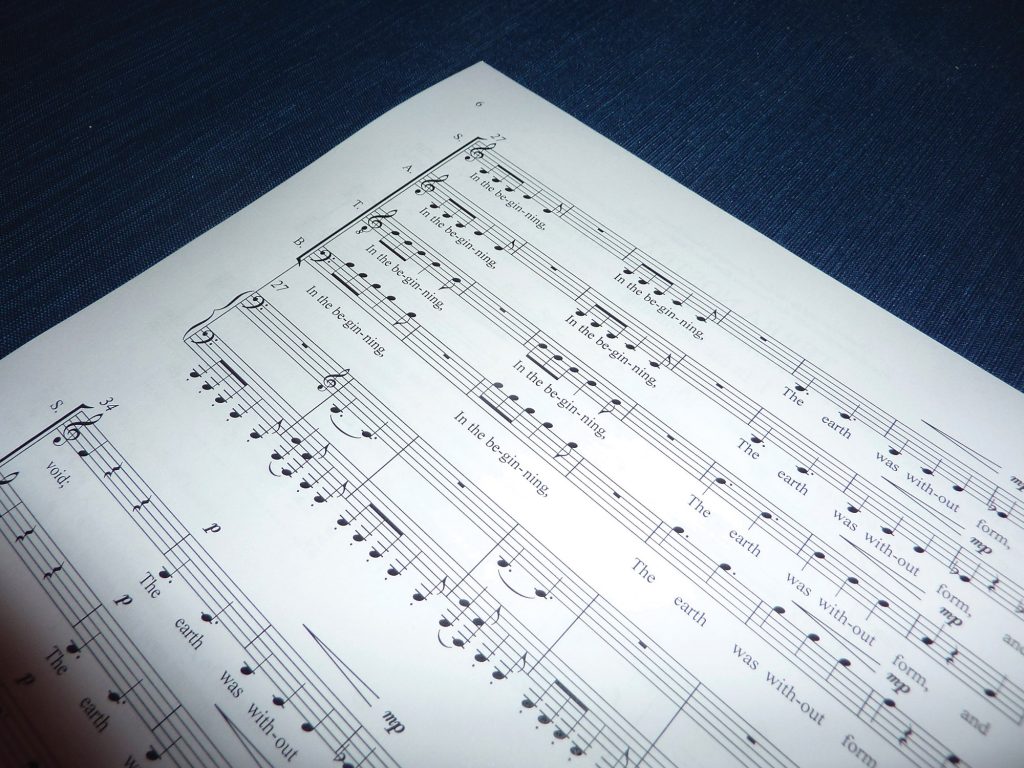

In the initial brainstorming stages, I sketch ideas using pencil and paper. Sometimes I’ll use my piano to tinker with possible ideas, while other times I’ll sketch directly from my head onto paper. I will work in this manner long enough for the ideas to take shape on paper; then I transition to a computer. I use a software notation program that allows me to hear the music that I write, as well as to create a beautifully engraved final score. Computer programs are a tremendous help to composers – you don’t have to wait until you rehearse with musicians to hear how your music will sound – but you need to use these programs carefully. Software programs never achieve an accurate, realistic balance between instruments so composers must account for balancing issues themselves. Nonetheless, I find this playback to be very useful, as I can check to ensure that my rhythms, tempi and pitches are to my liking.

For a while, I am conscious of every decision that I make while composing; however, the further I get in composing a piece, the more these decisions are being made subconsciously.

Every now and then, I need to evaluate what I’ve composed thus far. Is the music on the right track? Do the various musical ideas work together or has something shifted? While these assessments are valuable for a piece of any length, I find them to be even more important when composing a long piece. For example, when I wrote my piece Sanctuary for violin, cello and piano, I wanted the piece to start at a point of complete relaxation and, over the course of 13 minutes, progressively get more and more tense. This movement ends at a moment of extreme tension, which nicely sets up a very quiet beginning to the second movement. The first idea I composed seemed suitable to open the first movement, but after brainstorming additional ideas, I realized that the initial material would work far better if it occurred around the fourth minute. What had changed? I finally realized that my first idea had too much tension already and couldn’t be used at the beginning of the work. This realization helped me to compose a slow, mysterious opening that gives the piece ample room to grow.

Occasionally while composing, I will arrive at a spot where I can’t seem to progress any further. Some people call this writer’s block. When I reach such an impasse, I back up to a few measures prior to the trouble spot and rewrite the passage at least two additional times, each time leading to a different musical outcome. Within an hour or so, I have developed three or more possible options to consider. Not only does this method usually unearth a new way to proceed, but it supplies additional musical material that I can use elsewhere in the piece. This strategy also enforces the point that there’s no one exact path that a composition needs to follow; instead, there are several potential paths, each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

Once all of the notes are in the computer, I proceed to the final stage of composing: adding all of the details. These details include anything that shapes the music and gives it nuance. While these details may not seem as important as the choosing of pitches and rhythms, the truth is quite the opposite. Imagine hearing an entire orchestra playing loudly, followed by a moment of silence and then a single trumpet enters quietly. Now imagine if the orchestra plays very quietly and – without a moment of silence – the trumpet enters obnoxiously loud. While the notes and rhythms didn’t change between these scenarios, the details did and with startlingly different results.

Part 3: Post-Composition

Now that the composing phase is complete, I move on to proofing the full score and individual parts. I don’t particularly enjoy this phase – it is tedious compared to the excitement of composing – but if I don’t work carefully, then rehearsals could be disastrous as the instrumentalists encounter mistake-laden scores. In addition to a full score that shows all of the instruments that play in the piece, each instrument requires its own individual “part” (for a string quartet, this would result in four separate parts for the ensemble’s two violins, viola and cello). Once I have made all of the instrumental parts, I check these against the full score three times to ensure that I have caught inconsistencies and errors. This phase can easily take just as long as composing the piece, if not longer, depending on the number of instruments involved.

I also need to give the piece a title. Technically, this can happen prior to composing the work, or at any stage along the way, including after composing is done. Sometimes, I’ll think of a title that shapes the brainstorming phase of pre-composing. This was the case with the double bass and piano piece; once I figured out that the piece would reference film noir, I easily came up with the title Noir Vignettes. At other times, I struggle to find a suitable title even after the piece is completed. Recently, I composed a piece in honor of Cedille Records’ 25th Anniversary season. James Ginsburg, the label’s president, mentioned that he had an interest in street musicians (or “buskers”) he encountered in the city of Prague. The word “buskers” didn’t appeal to me as a title, nor did a string of unfortunate titles that followed. I finally decided on Bohemian Café, as it aptly describes the carefree, freewheeling atmosphere that I invoke with the music.

No piece is ever complete until I have rehearsed it with performers.

No piece is ever complete until I have rehearsed it with performers. In this phase, I can make adjustments to various musical elements – increase a dynamic here or change an articulation there – to bring out more subtleties in the music. This is also the phase in which I finally discover what passages don’t sit well in a performer’s hands. Performers generally begin rehearsing without the composer present; I will listen to one or two rehearsals as the premiere draws near. This allows the musicians to work out the music for themselves and to create their own interpretation of my piece before I give them my thoughts.

The final phase of any piece is its premiere. This is a thrilling moment! My adrenaline is pumping throughout the event, from any pre-concert discussion I have onstage for the audience, to listening to the musicians play the piece, to conversing with audience members afterward.

I greatly enjoy this wonderful moment. At the same time, I am assessing the music as it is played, ascertaining where adjustments need to be made. I usually make a small round or two of revisions after the premiere, which I test out at the piece’s next performance. By the third performance, I have worked out all of the kinks and can finally consider the work finished. When the composing process is complete and I’m pleased with the final results, then I have successfully navigated the composing process from the first note to the final score.

Stacy Garrop’s music is dramatic, lyrical and programmatic, as she enjoys telling stories through music. Garrop received degrees in composition from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor (Bachelor of Music), University of Chicago (Master of Music) and Indiana University at Bloomington (Doctor of Music). She joined the Chicago College of Performing Arts in 2000. Garrop has received numerous awards and grants including a Fromm Music Foundation Grant, Detroit Symphony Orchestra’s Elaine Lebenbom Memorial Award, Sackler Prize and two Barlow Endowment commissions. Theodore Presser Company publishes her works, and her music is commercially available on 20 CDs. Garrop has been commissioned by the Minnesota Orchestra, Albany Symphony, Chanticleer, Chicago a cappella, Capitol Saxophone Quartet, Cedille Chicago, Gaudete Brass Quintet, San Francisco Choral Society and WFMT 98.7 FM.