Alumna Darlene Clark Hine is a pioneering scholar in the field of African-American women’s history and a recipient of the prestigious National Humanities Medal.

When she was a sophomore in high school, Darlene Clark Hine envisioned herself wearing a white coat in a laboratory, examining microbes and essentially having little to do with human beings.

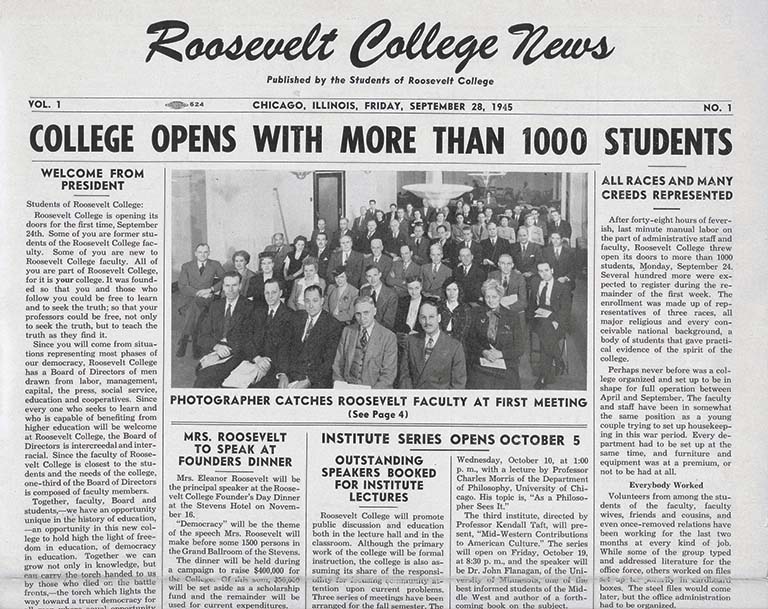

“That was my dream. That’s what I thought I’d be doing for all of my life,” she said. “But after my freshman year at Roosevelt University, I changed my major from biology to history and my life took a whole new direction.” That direction led all the way to the White House, where last summer she received a National Humanities Medal from President Obama for her groundbreaking studies on African-Americans, especially accomplishments of African-American women.

“Darlene is an architect in the field of African American women’s history, the co-author of the most widely used textbook in African-American history and the leading scholar in the United States of the black professional class,” said Martha Biondi, chair of the Department of African-American Studies and Hine’s colleague at Northwestern University, where Hine is the Board of Trustees Professor of African-American Studies and Professor of History. “She’s an intellectual leader, yet at the same time, she is a down-to-earth, warm, generous and thoughtful person,” Biondi said.

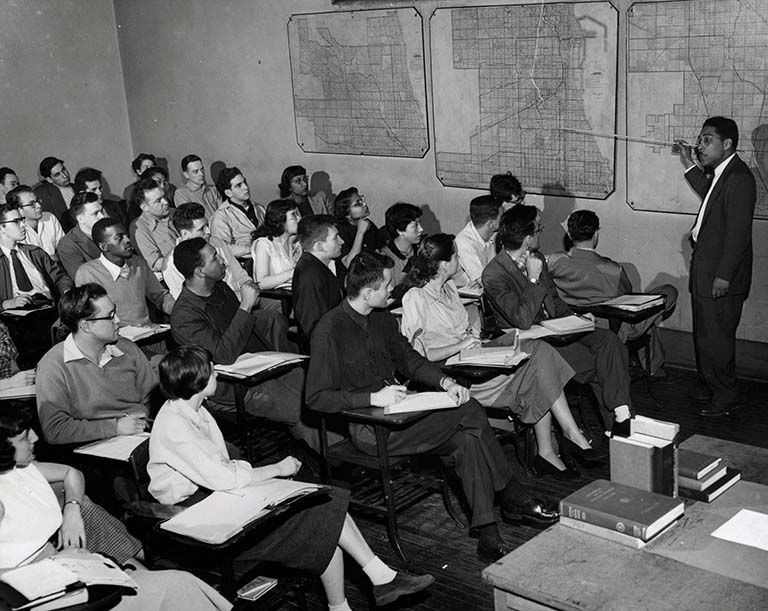

In a conference room at Northwestern (her office being too filled with books and papers to meet comfortably), Hine recalled that she was admitted to Roosevelt University on a scholarship, having been valedictorian at Chicago’s Crane High School. Her freshman year was 1964 and the Civil Rights Movement was at its peak. “As a biology student, all I knew was that this talk about racial inferiority made absolutely no sense to me, because as every scientist knows there’s only one race and that’s the human race. The color of your skin is neither good nor bad.”

On Feb. 3, 2013, at the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan, Roosevelt alumna Darlene Clark Hine moderated a panel celebrating the 100th birthday of civil rights activist Rosa Parks and unveiled a stamp in her honor.

The Roosevelt student concluded that hatred and turmoil must have something to do with history so she switched her major to history. Laughing, she said, “I wanted to write a lot of books, explain this to people and have everyone behave better.”

At Roosevelt, Hine observed history in the making, listening to Black Panthers Mark Clark and Fred Hampton when they spoke on the second floor of the University.

She took classes from some of the University’s most distinguished faculty members, including Charles Hamilton, author of Black Power, and Lorenzo Turner, chairman of the African Studies Program and author of Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect. Roosevelt “was a mecca for me,” she said. “I didn’t know enough to participate in the conversations and I didn’t become politically active, but I soaked it all in.”

Darlene Clark Hine, who taught at Michigan State University for 17 years, meets with former student Randal Jelks, who is now a professor at the University of Kansas.

Throughout her career, Hine always has stressed the importance of her Roosevelt education and she talked about it again in December when she was Roosevelt’s fall semester Commencement speaker and the recipient of an honorary Doctor of Social Justice degree. Her address to graduates described the “precious intellectual gifts” she received as a Roosevelt student.

“When my students learn that Dr. Hine was an undergraduate student at Roosevelt like them, they become all the more inspired,” said Erik Gellman, associate professor of history at Roosevelt who was mentored by Hine when he was a doctoral student at Northwestern. “Her textbook, The African-American Odyssey, always receives high praise from students in my African-American history courses for its fascinating telling of the central and rich history of African-Americans in America.”

“I had entered a universe that I never knew existed. And that was the beginning of my commitment to telling the truth, to lifting the veil, to shattering the silence about black women in American history.”

After graduating from Roosevelt in 1968, Hine went to Kent State University to further her studies with August Meier, one of the nation’s foremost authorities on race and black history and a former Roosevelt professor. But her time there was marred on May 4, 1970, when members of the Ohio National Guard shot students who were protesting the Vietnam War. Hine was the only black student to witness the confrontation. “I was a historian in training and thought I should be there to observe things,” she said. “The shootings were so profoundly disturbing that I basically retreated to the library and didn’t come out for decades.”

Hine’s first job after receiving her PhD from Kent State was at South Carolina State College in Orangeburg, where she taught for three years before returning to the Midwest to teach at Purdue University from 1974 until 1987. At that time, there were only a handful of black women history professors in the United States and she was the only tenured African American female professor in the entire state of Indiana.

Her career took an important turn in 1980, when Shirley Herd, an Indianapolis schoolteacher and president of the city’s chapter of the National Council of Negro Women, persuaded Hine to write a history of black women in Indiana. From that point on, much of Hine’s research has focused on African American women. “At that time, no one thought black women were worth studying,” Hine explained. “I had entered a universe that I never knew existed. And that was the beginning of my commitment to telling the truth, to lifting the veil, to shattering the silence about black women in American history.”

President Barack Obama presented Hine with a 2013 National Humanities Award at the White House on July 28, 2014.

Aldon Morris, professor of Sociology and African-American Studies at Northwestern, said Hine is a groundbreaking historian because she demonstrated for the first time that experiences by black women could no longer be subsumed under the history of black men or that of white women. “Her meticulous scholarship has focused a bright historical light on black women, showing they have been crucial actors on the stage of history throughout the life of the nation,” he said.

Hine’s first major book on African-American women, a 1989 study of black nurses called Black Women in White: Racial Conflict and Cooperation in the Nursing Profession, 1890-1950, won numerous awards and professional acclaim. Originally intended to be a history of blacks in the medical profession, Hine changed her focus when she came across a 1924 study on black nursing schools and hospitals while doing research at the Rockefeller Archive Center in Pocantico Hills, N.Y.

A tribute to the first three generations of black nurses, the book highlights nurse Mabel K. Staupers, who helped break down color barriers in nursing at a time when segregation was entrenched in the country and military. “In the 1940s, Staupers took it upon herself to lead a struggle to desegregate the armed forces medical corps and destroy a quota system that permitted very few black women nurses to serve,” Hine said.

The Northwestern professor loves nothing more than rolling up her sleeves and digging through old documents in the archives of libraries and philanthropic organizations. “Almost by surprise, you’ll come across a name, a code, that will lead you to something else and that will lead to something else and before long you can begin to craft a narrative. But it can take weeks or months of investigating,” she said with a smile. That research has led to more than a dozen books on race, class and gender, including The African-American Odyssey and The History of Black Women in America.

In addition to being a nationally recognized scholar, Hine has a reputation in the higher education community for being an outstanding mentor to students pursuing doctoral degrees. During her career, she has trained 35 PhD students, helping to produce a new generation of pioneering historians. “Darlene is encouraging to the uninitiated and a tough-as-nails demanding teacher when she prepares future scholars,” said Morris, her Northwestern colleague.

Christopher Reed, professor of history emeritus at Roosevelt who has known Hine for four decades, said that even when Hine joined Northwestern in 2004 after spending 17 years at Michigan State University, she continued to train her former students. “That was an unusual gesture within the academy and one that ensured continuity for her doctoral students,” he said.

Hine, who taught at Roosevelt in 1996 as the Harold Washington Distinguished Professor of History, has also been a leader in national organizations. She was the first African-American woman president of the Southern Historical Association and the second African-American woman president of the Organization of American Historians, which honored her service by establishing the Darlene Clark Hine Award, given annually to the author of the best book in African-American women’s and gender history.

Hine said “the defining moment in my career and in my life” was receiving the National Humanities Medal from President Obama. Her citation proclaimed: “Darlene Clark Hine, historian, for enriching our understanding of the African American experience. Through prolific scholarship and leadership, Dr. Hine has examined race, class and gender and shown how the struggles and successes of African American women shaped the nation we share today.” Months after receiving the award she is still overwhelmed. “When they first contacted me, I thought they were asking for a letter of recommendation for somebody else,” she said.

Hine won’t tell where she keeps the medal and she refuses to wear it. She has, however, received plenty of comments about the honor from friends. Her favorite is: “You deserve this medal because everybody messed up our history and you got it right.”

Publications by Darlene Clark Hine

Black Victory: The Rise and Fall of the White Primary in Texas

University of Missouri Press, New 2003 Edition

Black Women in White: Racial Conflict and Cooperation in the Nursing Profession, 1890-1950

Indiana University Press, 1989

Hine Sight: Black Women and the Re-Construction of American History

Indiana University Press, 1996

Black Europe and the African Diaspora

(Co-editor with Trica Danielle Keaton and Stephen Small)

University of Illinois Press, 2009

Beyond Bondage: Free Women of Color in the America

(Co-editor with David Barry Gaspar)

Indiana University Press, 1996

The Harvard Guide to African-American History, Vol. I

(Co-editor with Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham and Leon F. Litwack)

Harvard University Press, 2001

A Question of Manhood: A Reader in U.S. Black Men’s History

and Masculinity Vol. I and II

(Co-editor with Ernestine Jenkins)

Indiana University Press, 1999

“We Specialize in the Wholly Impossible” a Reader in Black

Women’s History

(Co-editor with Wilma King and Linda Reed)

Carlson Publishing, 1995

Black Women in America, Historical Encyclopedia Vol. I, II and III

(Co-editor with Elsa Barkley Brown)

Oxford University Press, 2005

The African-American Odyssey

(Co-author with William C. Hine and

Stanley Harrold)

5th Edition, Pearson Education, 2011