Professor Anne-Marie Cusac and photographer Thomas Ferrella on community violence and the memorials left behind.

At a time when there is one shooting after another in Chicago, Roosevelt University Journalism Professor Anne-Marie Cusac and photographer and retired medical doctor Thomas Ferrella are taking a different approach to understanding the violence epidemic.

Over the last year, Cusac and Ferrella visited nearly 50 Chicagoland murder memorials where deaths have occurred and where those who have become just another grim statistic are being remembered by families and communities.

A memorial of teddy bears and liquor bottles.

“We wanted to look at more than just the problem,” said Cusac, an award-winning investigative reporter who has traveled some of Chicago’s most violence-prone streets with Ferrella, who is also a Wisconsin multimedia artist. Frequently accompanied by guides, the two have visited memorials in nearly a dozen Chicago neighborhoods and suburbs.

During their trips, Ferrella photographed stuffed toys, votive candles, wooden crosses, liquor bottles and other adornments, while Cusac interviewed neighbors, loved ones and passersby who know the back stories of the memorials.

R.I.P. Smokkey is site where a mother memorializes her son on Thanksgivings with a turkey dinner.

The result of their efforts, an exhibit called “Not Forgotten: Chicago Street Memorials,” opened last fall at Roosevelt University’s Gage Gallery at 18 S. Michigan Ave., Chicago. The show contains 34 photos and related interviews about memorials to death and violence in Chicago’s Auburn-Gresham, Back of the Yards, Brighton Park, Englewood, Gage Park, Little Village, Pilsen, Rogers Park and Uptown neighborhoods, as well as in Cicero and Evanston, Ill.

“Their work has given us a better understanding of the kind of grieving that goes on after the violence is over and the media has moved on,” said Michael Ensdorf, director of the Gage Gallery and curator of the exhibit.

Cusac and Ferrella documented memorials connected with some of the city’s recent and most notorious murders, including the gang-retaliation shooting of 9-year-old Tyshawn Lee in an Auburn-Gresham alley and the slayings of six members of the Martinez family at their home in Gage Park.

They also photographed and talked to people about markers for lesser-known crimes. At one location, there were offerings of food in the memory of a loved one. “I just want to sit and talk to my son,” Cusac was told by a mother who delivers a plate of food each Thanksgiving to the Brighton Park marker with the words “R.I.P. Smokkey,” which lies on the spot where her son was killed 14 years ago. “When I’m here, I know he’s with me. I let out my tears and I have my moments with him.”

To remember another tragedy, residents from an Uptown high-rise apartment building established a memorial to help them process the unimaginable — a newborn baby being thrown out an 8th floor window. “My cousin, because she had a newborn baby, put out Pampers, a blanket, teddy bears, flowers,” a woman who resided in the building explained to Cusac. “And then it just kept building,” a man at the site told Cusac in response to the woman’s comments.

“With this project, we gain an understanding of how people deal with hurt, trauma and loss,” said Cusac, who collected more than 30 hours of tape recordings. “It’s a project whose message, quite frankly, is as much about love as it is about violence.”

Both Cusac and Ferrella have previously delved into life’s underbelly. As an investigative reporter for The Progressive in Madison, Wis., Cusac uncovered pervasive and sometimes fatal torture of inmates inside America’s prisons and jails, leading her to write the nationally recognized book, Cruel and Unusual: The Culture of Punishment in America. Ferrella was a trauma doctor for 30 years in a Madison hospital emergency room where he treated people with injuries and conditions that at times were horrific.

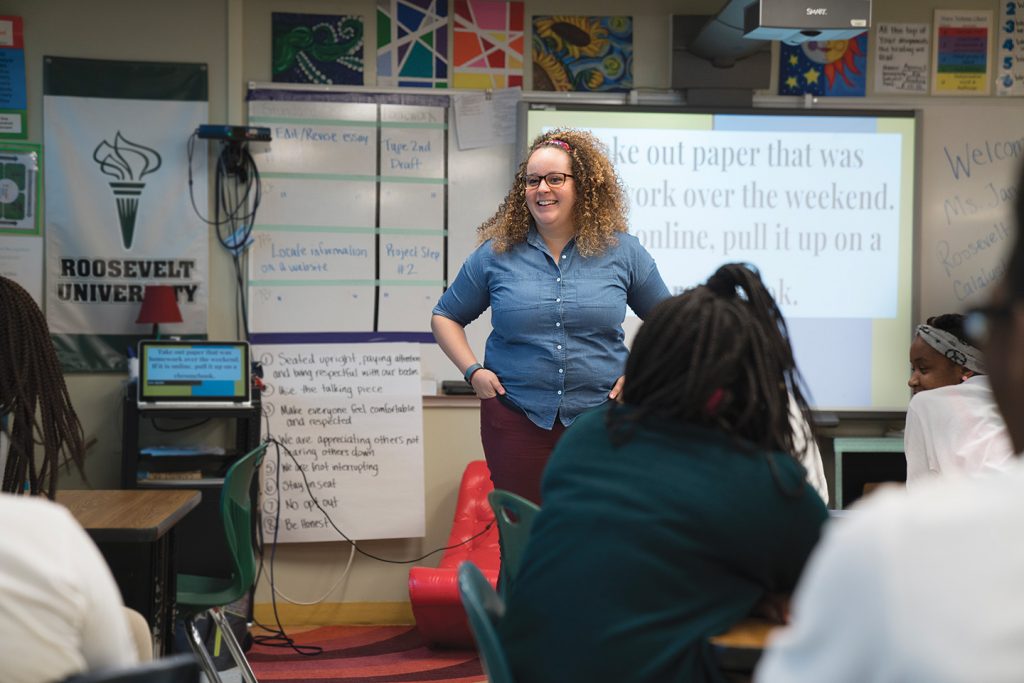

Roosevelt Journalism Professor Anne-Marie Cusac gathers facts.

In one case, he cared for a young woman who was brain dead after being hit by a car while crossing a street near his home in Madison. Shortly after her death, Ferrella noticed teddy bears, notes, flowers and balloons at the spot where she had been struck. It got him thinking that memorials were a beautiful and personal phenomenon worth documenting. Since then, he’s photographed 80 roadside memorials in Wisconsin.

“I needed someone to investigate their stories, including who built them, how they’re organized and what they mean to the community,” said Ferrella, whose friend recommended Cusac.

That is the underlying philosophy that guided the memorial project and what prompted Cusac and Ensdorf to ask Ferrella to consider expanding his reach from Wisconsin roadside memorials, which are mainly for drunk-driving victims, to Chicago street memorials, which largely remember those who have been murdered.

A memorial for a newborn thrown from a Chicago high-rise.

“I felt we could fulfill more of the University’s social justice mission by looking at how real people are dealing with the problem of violence in their communities,” said Cusac.

“I’ve taken care of my share of down-and-outers as well as shooting victims,” said Ferrella, who retired as an emergency room doctor about three years ago in order to pursue his artistic career. “I have seen all sorts of tragedies, but they have always been on my turf where I’ve been in control. This was a completely different experience. I found that a lot of what we did required knowing how to approach people without intimidating them,” he added. “I credit Anne-Marie for being able to do that. She’s taught me how to be a better listener.”

A memorial for six family members killed in Chicago’s Gage Park.

Angalia Bianca, one of the team’s guides who does outreach and evaluation for the anti-violence organization CeaseFire, believes the project is successful because it gathers opinions from those whose voices are rarely heard. “A lot of people just assume that these are memorials to gangbangers, but the truth is that they’re human beings first – and all of us need to understand that,” said Bianca.

One of the most difficult questions Cusac routinely had to ask is “Why is this happening?”

“Many of the people we interviewed have been part of the problem. They’ve seen what violence does to life and are no longer shocked by it,” said Cusac. “We looked at their hurt and found that those we talked to are becoming people who want to stop the violence that has come back to haunt them.”

Liquor bottle street memorial.

“This is not really a project about a problem like violence,” she said. “It has to do with cultural change in the form of street memorials expressing grief and the desire to comfort.”

At 73rd and South Morgan in Englewood, one man who had seen his share of violence talked with Cusac about the Hennessy-bottles memorial erected for an unknown victim.

“I felt we could fulfill more of the University’s social justice mission by looking at how real people are dealing with the problem of violence in their communities.”

Anne-Marie Cusac, Professor of Journalism

“Pouring out a little liquor for him. It means paying your respect for the person who ain’t here,” said the man. “You pour it on the Earth so he can drink it. Because they say when they die they go to heaven, but they come back to Earth to try to help to show people there are better ways.”

Frankie Sanchez, an interrupter with CeaseFire, showed Cusac and Ferrella a fence memorial called “Haz Paz” that had long been in the community before being painted over after a period of many shootings. It is one of the highlights of the show. “We’ve had so many guys killed over here,” a man at the memorial told Cusac. “Haz Paz means make peace.”

A memorial for six family members killed in Chicago’s Gage Park.

Brother Jim Fogarty, executive director of Brothers and Sisters of Love, said it’s not unusual to have members of the media accompany him as he ministers to gang members and others who are engulfed in Chicago’s street violence.

“The people who are out there are in need of a way to express their grief,” said Fogarty, who has seen memorials to murder victims come and go, sometimes on the order of police.

“The nice thing about this project is that these memorials become something permanent,” said Fogarty. “They are a means for healing wounds, and I know that, time after time, I heard those we visited in their communities tell us: ‘Thank you. We appreciate that you’re interested.’”

Cusac and Ferrella will be showing their exhibit on Wisconsin roadside memorials in Madison at the Arts and Literature Laboratory in May 2017. The two are also considering doing a book about memorials.

Visit wisconsinroadsidememorials.com to learn more about the project.

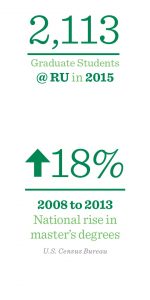

Joseph Chan, dean of the Heller College, said Vincent and many other individuals like him are doing the right thing by taking graduate school classes. “An advanced education provides the breadth and depth of knowledge that is required in a rapidly changing environment,” he said. “It transcends the know-how of today with the know-what of tomorrow.”

Joseph Chan, dean of the Heller College, said Vincent and many other individuals like him are doing the right thing by taking graduate school classes. “An advanced education provides the breadth and depth of knowledge that is required in a rapidly changing environment,” he said. “It transcends the know-how of today with the know-what of tomorrow.” Roosevelt offers 46 master’s, diploma and doctoral programs, mostly in areas that lead directly to jobs. For example, the College of Education has partnered with schools in Schaumburg to create an off-campus master’s program for teachers who want to become principals and teacher leaders.

Roosevelt offers 46 master’s, diploma and doctoral programs, mostly in areas that lead directly to jobs. For example, the College of Education has partnered with schools in Schaumburg to create an off-campus master’s program for teachers who want to become principals and teacher leaders.