In 2013, finally heeding the advice of experienced friends and colleagues, I decided to apply for a Fulbright fellowship.

Named for its founder, Senator William Fulbright, this 70-year program has fostered educational exchanges between the United States and countries around the world. Its goals have remained true to Senator Fulbright’s vision: to promote mutual understanding and international co-operation.

As I scrolled through the surprising number and variety of opportunities on the Fulbright website, the position of Distinguished Chair in American Studies at the University of Southern Denmark in Odense stood out as an attractive match. Having taught American literature from an interdisciplinary perspective for a long time, I saw this position as my way to help achieve the Fulbright goals.

I wasted no time in assembling the application materials and my three recommenders promptly submitted letters of support. Then the waiting began. Seven months later, I was thrilled when the acceptance letter from the Danish-American Fulbright Commission arrived.

In addition to expressing congratulations, the letter also detailed how much I had to do. First, I had to request leave from Roosevelt, which was generously granted. In addition to complying with visa requirements and addressing all of the practical considerations of living away, I had a lot to learn about Denmark. Scandinavia had never been on my itinerary in the handful of times I’d been to Europe.

A quick search turned up many references to the Danes as the “happiest people on earth,” countered by occasional criticism that cast them as cold and unwelcoming. I decided to keep an open mind. Fortunately, the Danes I met were the happy ones. Thanks to their genuine friendliness and the vital culture I came to appreciate, I had a fantastic year. At nearly every step along the way, there was something new to learn and to experience, all of which has subtly re-focused my perspective.

With only 5.5 million people, Denmark realized that maintaining a Danish-only policy could lead to isolation. So throughout their formal education, students learn English.

For Americans contemplating living in a foreign country, language can be a barrier to making the leap. Denmark minimizes the obstacle. Although it’s not officially a bilingual culture, most Danes speak English very well. With only 5.5 million people, Denmark realized that maintaining a Danish-only policy could lead to isolation. So throughout their formal education, students learn English.

To be sure, I had moments of uncertainty. I couldn’t read a local newspaper or follow a television broadcast, signs were often a mystery and on early trips to the grocery store I returned home with something other than what I thought I had purchased. But Danes are very approachable and easily shift to English for those who need help.

I started off with the best intentions of learning the language. So I was surprised when some people discouraged the idea. There’s a common riddle in Denmark that suggests their reason:

Q: Why is Danish the language spoken in heaven?

A: Because it takes an eternity to learn it.

Granted, to American ears, Danish is a challenge. The vowel sounds are subtly complex and Danes drop consonants seemingly indiscriminately. On more than one occasion I had to ask someone to write out the name of a street because I simply couldn’t match what I was hearing to the names on the map. Forget about trying to understand directions on the telephone. This aural difficulty and the unlikelihood of reinforcing what little I might learn upon returning to the U.S. persuaded me to take the easy way out. Although I have a shadow of regret, I think those who advised me had my best interests in mind. In the end, I think that the time I would have dedicated to puzzling over foreign sounds was better spent encountering the culture face to face.

Danes from across the political spectrum staunchly defend their cradle-to-grave social welfare system. Although high tax rates add significantly to the cost of living, Danes accept taxes as a worthwhile social investment. The nation’s middle-class stability is founded on shared responsibility for life-long education, universal health care, generous parental support, unemployment assistance and secure retirement income.

These cultural attitudes are reinforced by a practical approach to solving problems. Take, for example, their bicycle culture. In the 1970s, increased reliance on cars was causing extreme congestion, choking off the quality of life. As a result, they instituted high taxes on cars – adding as much as 180% to the sticker price – as a disincentive. Simultaneously, they committed to building and maintaining safe bicycle routes both in cities and in the countryside. Today, while many still own cars, a solid majority of Danes ride bicycles. It’s common to see even elderly people pedaling around, promoting health and fitness as well as relieving traffic congestion.

Because my wife and I ride bikes a fair amount, it seemed a good idea to make our first acquaintance with Denmark on two wheels. We mapped out a leisurely eight-day tour of several islands. The largest of these, Funen, where we would be living in the city of Odense, is centrally located between the Jutland peninsula to the west and Zealand, site of Copenhagen, to the east. We rode through quaint villages with traditional, white-washed, step-gabled churches, and across rolling farmlands with thatched-roof houses and stone barns. And then from the modest landscape rose Egeskov Slot (pronounced Áy – us – coh Sluh –see what I mean?), a sixteenth-century castle with world-class gardens.

After this close-up introduction to the Danish countryside, we headed to Copenhagen for the Fulbright orientation. The two-day meeting focused on useful information about Danish life and educational culture, but it also provided an opportunity to meet my Fulbright cohort.

The six Fulbright faculty or professional fellows and seven Fulbright students were accomplished in a wide array of fields – health-care policy, law, engineering, ceramics, finance, mineralogy, mathematics, bio-medical research, public art focused on sustainability education, and off-shore wind energy. After a tour of one of the world’s most picturesque cities, we scattered to our postings around the country.

A “Passing Grave” (c.3,500 BCE) on the island of Aero in Denmark. Photo by Judy Frei

My teaching experience afforded an easy transition. My professional responsibilities were quite familiar: two courses each semester – an American literature survey in each term, a Mark Twain seminar for seniors in the fall, and a graduate seminar on the literature of American race relations in the spring. My experience in the classroom was not markedly dissimilar to teaching in the U.S. But there are notable differences in the structure and expectations of Danish education. The most significant structural difference is that all five of the national universities are public. And not only is tuition free, but students also receive a stipend for enrolling. Each university has a different emphasis, with very little competition among them. For example, USD has the only American Studies program. Students who want to study that subject area must commute or move to Odense.

While faculty determine the specific content of their courses, a national educational body determines the volume of work to be assigned across the curriculum. Reading requirements are roughly 30-40 percent less than what I typically assign in a course at Roosevelt. Students are free to do as much or as little of the assigned reading as they choose, or to attend class meetings or not.

Student success is based solely on the final exam. Although the final exam is a high-stakes performance, students have multiple opportunities to succeed. Anyone not earning a passing grade may sit for a follow-up exam two months later. If needed, an additional opportunity is available six months after that.

My Danish colleagues see shortcomings in the system and would prefer to have more authority over academic protocols. For example, they contend that students would benefit from a more rigorous volume of reading and writing assignments throughout the semester, something closer to the practices at U.S. universities.

While I agree with their call for more writing, my Danish experience has prompted me to reconsider the volume of reading I typically assign. Danish faculty also criticize students’ irregular attendance, with concern that a few may enroll simply to take advantage of the stipend benefit. Although this may be true in some cases, attendance in my courses was consistent and regular, about what I see at Roosevelt. In fact, I was impressed by the turnout for 8 a.m. class meetings, especially because some students commuted as much as two hours by train and bus.

Denmark’s population is much more homogeneous than in the U.S., and this was reflected in the students I met. The large majority of them were Danes, though some were either immigrants or born in Denmark to immigrant parents, mostly from the Middle East. Although the current political climate has led to a closed-border policy, Denmark has traditionally welcomed refugees. Still, those who arrived under the more liberal policy and even their Danish-born children have experienced a social divide, an indication that the egalitarianism has not been fully achieved.

Egeskov Slot built in 1554 on Funen in Denmark

A few of my students were from other European countries, enrolled through the EU-sponsored Erasmus exchange program. Four Chinese students studied with me throughout the year. Like me, they were enjoying the opportunity to live abroad and to learn about another culture.

Danish students have very informal relationships with their faculty and are curious about them. At receptions and social events that bring faculty and students together, I had many conversations with students about different aspects of American life. They know a lot about the U.S. and are eager to know more.

I’ve maintained contact with quite a number of the students. Some have asked me to write letters of recommendation for applications to graduate school, internships or to study in the U.S. One of my Danish students is studying at Roosevelt this spring. I sponsored one of my students to conduct field research in the U.S. for her bachelor’s thesis on Native American language preservation. Before heading off to interview educators in South Dakota and Wisconsin, we hosted her for a few days and showed her Chicago sites. These personal contacts and correspondence with students continue to remind me of the value of my time in Denmark.

At a meeting of the American Studies student organization on the eve of the 2014 U.S. mid-term elections, I was invited to explain this phase of the political process. Both the turnout and the volume of questions were impressive. In return, students were an educational resource for me. Six months later, they explained to me how their 2015 parliamentary election had realigned their government.

Regardless of the outcome, it was a refreshing change to be in a country where the publicly-funded national campaign is compressed into three weeks.

Regardless of the outcome, it was a refreshing change to be in a country where the publicly-funded national campaign is compressed into three weeks. Political advertising is limited to uniform-sized placards posted on light poles – no robo-calls, mass mailings or television ad blitzes. The main outlets of the campaign are two televised debates, during which candidates from the 10 parties (yes, 10 parties) highlight the differences in their platforms. Voter turnout is quite high – almost 86 percent. And on the day after the election, the new government is installed while the various parties continue to negotiate over coalitions that will optimize leverage.

As much as I was able to learn on campus, I was even more enriched by the community emphasis on the arts as necessary to their quality of life. Communities both large and small support their local Kulturhus, where lectures, workshops, exhibits of a variety of arts and crafts, and musical performances take place.

Denmark’s music scene is diverse in ways that I had not anticipated. While Scandinavian folk holds its own among the more dominant forms of contemporary pop, Danes are jazz enthusiasts, which is more popular there than in the U.S. In the 1960s and ’70s, a number of African-American jazz musicians — Dexter Gordon, Ed Thigpen, Thad Jones, among others — emigrated to Denmark, finding both a community of Danish jazz players with whom they collaborated and a society more musically and socially accepting. In addition to hearing accomplished players at weekly sessions at a jazz club in Odense, I attended a concert of avant-garde jazz at the Nordic cultural center, featuring musicians from the Faroe Islands.

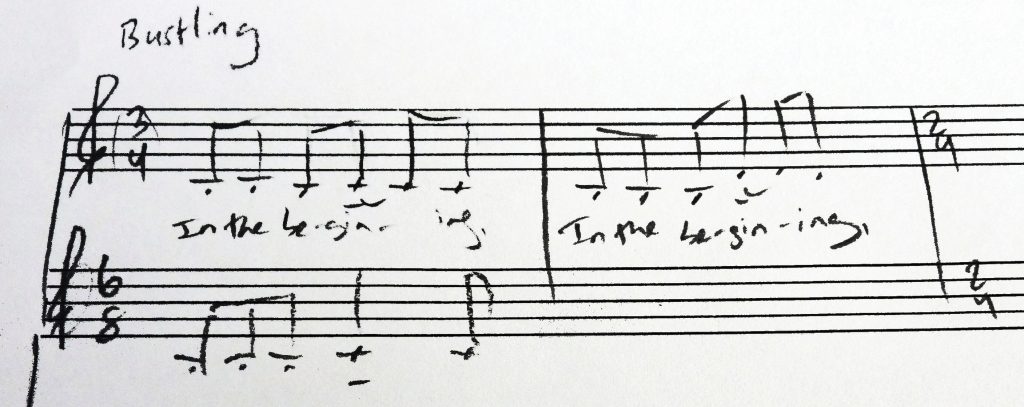

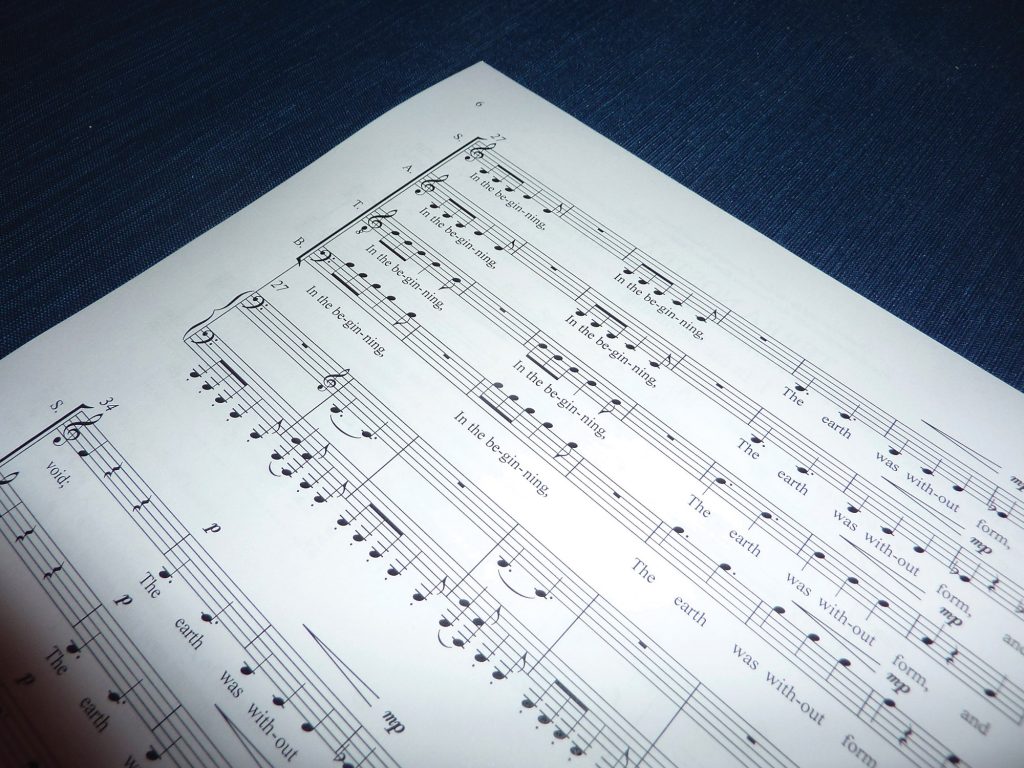

My year in Denmark coincided with the 150th anniversary of the birth of Carl Nielsen, Denmark’s most revered composer. An American Studies colleague and another Danish friend sing in choirs that performed concerts during this year-long celebration. One memorable performance was in Nørre Lyndelse, Nielsen’s childhood hometown. Listening to his music in the small church where his musical career began was a memorable authentic moment.

The other admired cultural figure of the region is Hans Christian Andersen. The author of famous tales like “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” “The Ugly Duckling,” and “The Little Mermaid,” Anderson was born in Odense. The city capitalizes on his celebrity much like Oak Park, Ill., promotes itself as Ernest Hemingway’s birthplace or Hannibal, Mo. claims Mark Twain. And like those two American figures, Andersen left his hometown in his teens.

Larry Howe touring on one of nearly 2,000 bike trails in Denmark. Photo by Judy Frei

As fulfilling as it was to learn so much about the history, society and culture of Denmark, the most gratifying aspect of my Fulbright experience, by far, was the friendship. My American Studies colleagues are extremely interesting and generous people. Their wealth of world experience, cross-cultural knowledge and good humor made for engaging and informative conversations and seamless connections among us.

I was frequently surprised at how current they are with American popular culture and contemporary issues in politics, business and sociology. A few root for one or another NFL team. The most dedicated fan and I had adjacent offices and he was eager to talk on Mondays about the weekend’s results. He even followed the NFL Draft and was thrilled to discover that it was held at Roosevelt University.

Another colleague invited us to see her roller derby team skate against a team from Aalborg. In addition to events like this, Danish friends welcomed us into their homes. There was always food and drink – smørbrød and beer, or coffee and wienerbrød (ironically, “Danish” pastry is an imported delicacy, as the name “Vienna bread” suggests). Try as I might, I never acquired the taste for pickled herring or a chaser of schnapps.

In winter, Danes light their homes with the glow of candles. Although the climate is not as severe as it is in Chicago, winter daylight hours are short. As a point of comparison, a Chicagoan would have to travel north almost 1,000 miles to match the latitude of southern Denmark. While the candles soften the darkness of the season, potted orchids on the window sills of nearly every house are a reminder of sunnier days ahead. Offsetting the darkness of winter, the midsummer sky begins to brighten at around 3:30 a.m., and remains light as late as 10:30 p.m. So the social life moves outdoors and also lasts longer during those summer months.

The opportunity to live in Denmark for a year was fascinating in more ways than I had imagined. I grew so accustomed to the rhythm of life there that my return date crept up on me without much notice. Short-term vacations to visit new places have their benefits, but only an extended stay provides sustained cultural exposure and a durable connection to people.

The Fulbright goals of mutual understanding and international co-operation were certainly fulfilled for me. I hope that my Danish friends feel that I reciprocated. For the many opportunities of that year, I’m grateful to more than a few people and institutions – to my Danish friends, to the American Studies program at USD, to the Danish-American Fulbright Commission and especially to Roosevelt University for granting me the leave time that made this rewarding experience possible.

Of course, I’m grateful also to those colleagues who encouraged me to apply for a Fulbright in the first place. I’d be happy to play a similar role for Roosevelt colleagues, alumni, and students. Like I did, they might find it the opportunity of a lifetime.

Larry Howe recently celebrated his 20th year on the Roosevelt faculty. A native of Boston, he completed his bachelor’s degree and his doctorate at The University of California at Berkeley. He is the author of Mark Twain and the Novel: The Double-Cross of Authority (Cambridge University Press), and is co-editor of and contributor to two essay collections—Refocusing Chaplin: A Screen Icon Through Critical Lenses (Scarecrow Press) and Mark Twain and Money (University of Alabama Press, forthcoming 2016.) When he’s not teaching or researching a wide range of topics in American culture and film, he plays mandolin in Compass Rose Sextet, a world folk and gypsy jazz ensemble. He and his wife, Judy Frei, live in Oak Park, Ill.