Most people who know Roosevelt University professor Erik Gellman will tell you that he could have joined almost any college faculty in America.

The scholar of African American, working-class, and modern United States history interviewed with more than a dozen universities upon receiving a PhD and prize for best history dissertation from Northwestern University in 2006.

But Roosevelt isn’t just another university to Gellman, whose scholarship, activism and family background reflect the social justice values that the University was founded on in 1945 and has stood for ever since.

“Erik is a signal example of a Roosevelt teacher-scholar, a true believer in the Roosevelt experience and a public intellectual in the community,” said Bonnie Gunzenhauser, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences where Gellman teaches African American history, civil rights, social movements and modern U.S. history.

The winner of teaching awards and book prizes, the Roosevelt historian rejects the adage, “Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it,” preferring a more positive view of history’s significance. “It is vital to understand the past if we are to change the present,” said Gellman, whose aim during 10 years as a Roosevelt professor has been to be a force for racial and economic justice, using history as the vehicle.

Gellman applied his gift for linking history to the present through stories and images in two co-curated social documentary photography exhibits that drew hundreds of visitors to Roosevelt’s Gage Gallery. His activism on campus has included organizing national civil rights conferences, including one earlier this year that became a meeting ground for today’s young, leading firebrands and yesterday’s legendary 1950s and 1960s veteran activists.

“Erik was very aware of who we were and was really excited to become part of our story.”

Lynn Weiner, University Historian

Gellman is enthusiastic — and this can’t be overstated — about all things Roosevelt, including: the Mansfield Institute for Social Justice and Transformation, which gave him pointers in designing courses with social-justice-based classroom learning and field training; Roosevelt’s Murray-Green Library, which has a rare collection of oral histories of American labor leaders that he’s recommended as a resource to students and used in his own research; and the St. Clair Drake Center for African and African American Studies, where he is committed, as associate director, to keeping alive the name and furthering the scholarship and vision of the late St. Clair Drake, one of Roosevelt’s most beloved professors.

“One of the marks of citizenship is to be aware of your rights,” said the Rev. Calvin Morris, a Chicago activist, faith leader and historian who worked with Martin Luther King, Jr. in the 1960s and this past year team-taught a history course on Chicago at Roosevelt with Gellman. “Erik epitomizes what good citizenship is all about.”

“Erik has a passion for worker’s rights and preserving their history,” added Paul King, a 1974 Roosevelt alumnus who studied with Drake and also has been a pioneer in the fight for black inclusion in the nation’s construction industry. “He’s helped me get my papers in order for archiving,” said King, founder of the National Association of Minority Contractors and former leader of the United Builders Association of Chicago. “I trust and respect him as a historian and advocate.”

Gellman is a native of the suburbs of Buffalo, NY, a city that he lovingly calls an “underdog” with a reputation for “hard luck” in all things. One such example is the 1901 World’s Fair. “Buffalo was fortunate enough to hold the fair, but unfortunate in that it is remembered as the site of President William McKinley’s assassination,” he said half-jokingly.

“My family’s stories are unusual and have always made me feel like I had a different calling.”

Erik Gellman

Gellman has a great deal of pride for his hometown and upbringing. Growing up, he heard plenty of stories about family members standing up against injustices. When Gellman’s father was clerk of the U.S. Court of Appeals in Detroit, he helped write opinions favoring school busing between city and suburban Detroit schools in order to achieve regional desegregation and a quality education for all.

When one such decision was overturned through a follow-up opinion from the appeals court, the Detroit court’s late Justice George Edwards famously called the Supreme Court’s final ruling “a formula for American apartheid,” foreshadowing further segregation and white flight from cities into suburbs that would follow. “My dad is very philosophical,” and reflected often upon the poignancy of that moment in his and the nation’s past, according to Gellman. “It’s one of the things that influenced me on my journey as a scholar.”

Another remarkable story is about Gellman’s grandfather, whose parents had fled poverty in Eastern Europe in the 1890s to escape mob riots, known as pogroms, which targeted Jews. After serving with distinction in the Air Force, Jack Gellman became district attorney for Niagara Falls, NY. But he cut his own political career short when he intentionally bungled a felony assault case, costing him the next election, in order to avoid convicting a black man whom the attorney was convinced had been framed.

“My family’s stories are unusual and have always made me feel like I had a different calling,” said Gellman, who remembers interviews for faculty positions where he was bluntly asked: “Why would you choose this field?”

“I’ve come to see African American history as central to understanding American history,” said Gellman, who finds the more he teaches the topic, the more he appreciates its complexity and importance. Gellman didn’t get that kind of question at Roosevelt, where the study of African and African American issues has been a tradition since Drake joined the faculty in 1946.

“Erik was very aware of who we were and was really excited to become part of our story,” said Lynn Weiner, Roosevelt’s historian and a former College of Arts and Sciences dean who hired Gellman. “He’s smart and enthusiastic, and has a way of drawing you into his work.”

Gellman was not always a stellar student. In fact, he freely admits he was mediocre at best growing up in Buffalo. He didn’t fit in at the elite high school that his mother, a Danish immigrant, and father, a Buffalo businessman and attorney, hoped would remedy his poor reading skills.

College changed the trajectory for Gellman, who took his first course in African American history at Bates College in Lewiston, Maine. In 1996, he studied abroad at Oxford University in England, an experience he called “pivotal” to his becoming intellectually curious and driven by ideas. “I couldn’t slack off. I had to be prepared,” he said.

After returning home from Oxford, he wrote a 350-page senior thesis on the comparative history of African Americans and Jews in postwar social movements and graduated from Bates in 1997. He thereafter took a job in an immigration law firm in Boston, but differed from his colleagues in wanting to apply for graduate study in history rather than the law, and moved to Chicago to attend Northwestern University in 1999. At Northwestern, he immersed himself in the history of social movements in the 1930s and 1940s, resulting in his PhD dissertation and book, Death Blow to Jim Crow: The National Negro Congress and the Rise of Militant Civil Rights, which won a Roosevelt University outstanding faculty scholarship award in 2012.

His first book, The Gospel of the Working Class: Labor’s Southern Prophets in New Deal America, co-authored by historian Jarod Roll and published in 2011, also won an award from the Southern Historical Association for parallel stories about two Southern preachers — one black and the other white — who were early civil rights leaders.

Two books by Erik Gellman have won awards.

“What Erik has been able to do, in no small terms, is make history come alive,” said Roosevelt Emeritus Professor of History Christopher Reed. “He is a great storyteller and has been creative in expanding the academy’s as well as the general public’s appreciation for African American and civil rights history.”

Gellman’s interest in the African American experience flourished as a 1997 Benjamin E. Mays fellow at the largely black Morehouse/Spelman Colleges in Atlanta, where colleagues pushed him beyond his comfort zone, introducing him to neighborhoods, arts, food and culture unlike his own. It also piqued his interest in returning to Buffalo to seek out unfamiliar neighborhoods and working-class people that he’d only seen growing up in photographs mounted behind plexiglass on the walls of Buffalo’s subway stations.

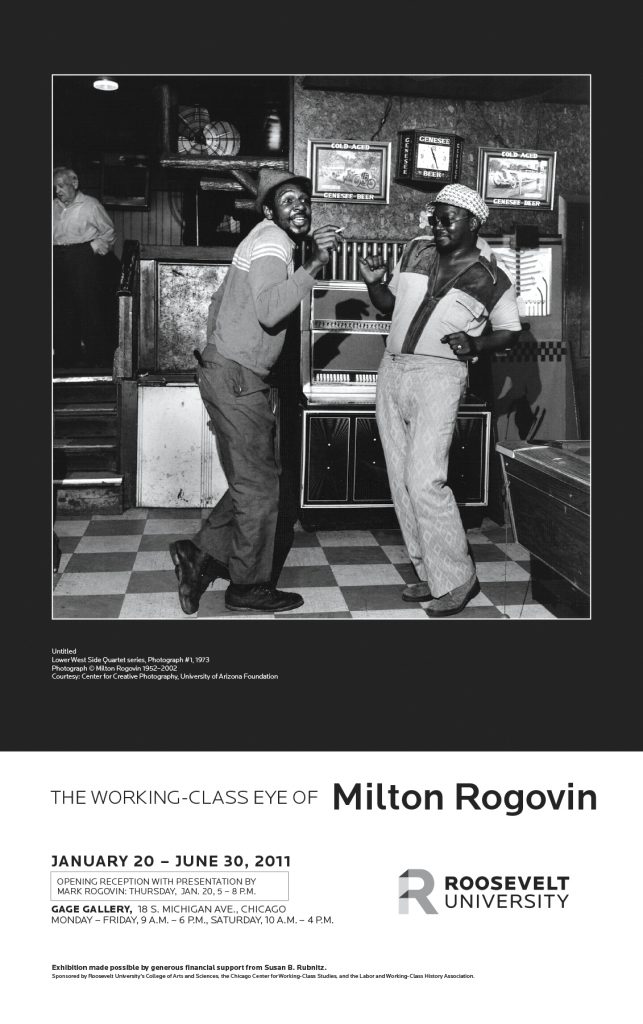

“I had heard of Milton Rogovin (Buffalo photographer) and knew of his talent for taking photos of people,” remarked Michael Ensdorf, professor of photography and Roosevelt’s Gage Gallery director, who collaborated with Gellman on The Working Class Eye of Milton Rogovin. “What I didn’t know, and gained, was an appreciation and understanding for the dignity and joy that Rogovin captured in his subjects.”

A poster from the Gage Gallery show, “The Working Class Eye of Milton Rogovin.”

Gellman visited with the 101-year-old Rogovin in his modest Buffalo home in preparing the exhibit, which garnered national media attention and burnished Rogovin’s legacy as a working class artist. Rogovin died immediately prior to the exhibit opening in 2011.

Late civil rights activist and Roosevelt University alumnus James Forman (center) was identified by Erik Gellman in the photo taken by Art Shay.

The experience led Gellman this past year to curate a second Gage Gallery exhibit of never-before-seen photos of Chicago street protests taken by Deerfield, Ill. photographer Art Shay during the 1940s through 1970s.

“Erik helped whittle about 50,000 of Shay’s civil rights images down to a few thousand, from which we selected for the show,” said Erica DeGlopper, Shay’s archivist who worked with Gellman on the project. “He didn’t think of this as just a gallery show,” she said. “He helped create a moving and complex narrative. Erik connected the dots on story lines and helped identify many people,” such as the late national civil rights activist and Roosevelt graduate James Forman.

Troublemakers: Chicago Freedom Struggles through the Lens of Art Shay was the Gage Gallery’s largest exhibit ever. It also spawned a new book project that will feature Shay’s photos and Gellman’s analysis of Chicago protest movements.

“The deeper he gets into it, the more valuable he’ll be as a Chicago activist and scholar. This is something that’s still emerging.”

Jack Metzgar, Roosevelt Emeritus Professor

“There are a number of young faculty members at Roosevelt who are really stellar, and Erik is one of them,” remarked Roosevelt Emeritus Professor Jack Metzgar, a leading working-class studies scholar and activist. “He has a lot of contacts in the community and real interest in our social justice history, and the deeper he gets into it, the more valuable he’ll be as a Chicago activist and scholar. This is something that’s still emerging,” said Metzgar.

Gellman believes there is no better place to come into his own as an authority on Chicago’s contemporary struggles for justice than Roosevelt University. “It was my first choice 10 years ago, and it is still my dream job today,” he said. When asked to elaborate on why, Gellman mentioned Roosevelt’s social justice history, his colleagues, but most of all, “many of the students here whose intellectual curiosity and hunger for social justice, cultivated at Roosevelt, make them unique.”